Published in The Daily Star on Wednesday, 18 October 2017

Rich become richer, poor get poorer

Reaz Ahmad and Rejaul Karim Byron

The poor’s share in the national income eroded further in the past six years, with the richer segment of the population having bigger stakes.

A government survey report, released yesterday, shows that the rich-poor inequality in terms of wealth accumulation has been widening in the country.

The poorest five percent had 0.78 percent of the national income in their possession back in 2010, and now their share is only 0.23 percent.

In contrast, the richest five percent, who had 24.61 percent of the national income six years back, now has a higher share — 27.89 percent to be precise.

“It shows the extent of concentration of household income by the higher household income group,” noted the report titled “Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) 2016” published by Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS).

With a big sample size, HIES is the most exhaustive nationwide survey carried out by the BBS usually once in five years.

With a big sample size, HIES is the most exhaustive nationwide survey carried out by the BBS usually once in five years.

The HIES 2016 also captured income shares of the bottom half (on economic scale) of the population to show that they used to command 20.33 percent of the national income in 2010 but it has now fallen further to 19.24 percent.

In other words, income of the people on higher economic scale has increased over the past six years since the last HIES was conducted in 2010.

Particularly, the top 10 percent of the population (in terms of economic standing) is now having more income share (38.16 percent) compared to what they had (35.84 percent) in 2010.

On the contrary, the lower echelon (bottom 10 percent of the population) now has half (just 1.01 percent) the income share it had (2 percent) in 2010.

According to the HIES 2016, the number of people in poverty has dropped to 24.3 percent from 31.5 percent in 2010, while the proportion of ultra poor also fell to 12.9 percent from 17.6 percent in six years.

However, the rate of poverty reduction (1.2 percent a year) actually slowed down in 2010-16 compared to that (1.7 percent a year) in the preceding five years.

Experts have stressed the need for accelerating farm sector growth that has been somewhat stagnant.

They also pointed out that the government must take measures to create jobs to take the benefits of the growth to all segments of the population.

AB Mirza Azizul Islam, former finance adviser to a caretaker government, thinks that the level of inequality is not that high.

He, however, noted that unlike the growth in the farm sector, that in manufacturing and service sectors cannot often equally distribute the benefits to all.

Azizul explained that the growth in the manufacturing sector is more capital-intensive, technology-driven and labour-displacing. The service sector growth also benefits the skilled and IT-savvy people more than the others.

He suggested expanding the social safety net programmes for the benefit of the poor.

Mustafizur Rahman, distinguished fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), however, expressed concern over the increasing inequality since the ’90s.

He said it is necessary to put in place a “distributive justice” so that everyone gets the benefits of the growth.” He reminded that one of the 17 SDG goals emphasised reduction of inequality.

Mustafizur suggested adopting fiscal and monetary policies that would ensure job creation and quality education.

World Bank Lead Economist Zahid Hussain said, “One major reason may be the composition of growth. It was largely driven by manufacturing and services. The contribution of agriculture, which employs over 42 percent of the labour force, to growth has been on the decline.”

“While incomes from manufacturing and services have grown, employment growth has been weak. Thus labour income growth may have been weaker than the growth of GDP. As a result, the incomes of the poor, who have only their labour to live on, grew far slower than income growth of non-poor, leading to increase in income inequality.”

He also identified the decline in remittance as another reason. “This could have slowed employment and wage growth in the rural non-farm sector, which uses a lot of poor workers.”

Dr Akhter Ahmed, who leads the operation of Washington-based think tank International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) in Bangladesh, said the 2016 HIES reflected that “the growth that we achieved was not pro-poor enough.”

He emphasised accelerating farm sector growth and shifting the “pure tenants” (the landless people) to more skilled areas of production, while investing more in farm research and development so that more crops are grown on less land.

Expansion of safety net programmes is not good enough. The beneficiaries of the safety net programmes have to be chosen carefully, he mentioned.

Besides, the state has to invest in human capital development and put emphasis on the quality of education rather than quantity, said Akhter.

Among other things, the HIES 2016 report reflected that household income, on average, has now risen to Tk 15,945 a month from Tk 11,479 in 2010. There has been an increase in percentage of safety net beneficiaries to 28.7 percent from 24.6 percent in 2010.

It also showed how some of the livelihood indicators got positive push with more people getting access to pure drinking water, sanitary latrines and pucca houses.

In the last six years, households with electricity increased to 75.9 percent from 55.3 percent, while mobile phone users rose to 92.5 percent from 63.7 percent.

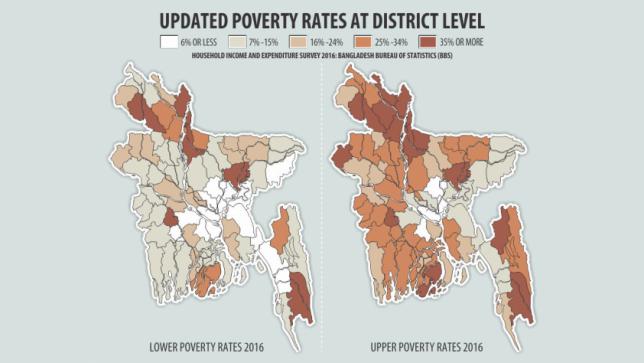

The HIES 2016 also reflected on regional variations in distribution of poverty incidence.

In 31of the 64 districts in the country, percentage of ultra poor is higher than the current national average (12.9 percent), it said.