Originally published in Briefing 21 of the Future United Nations Development System in September 2014.

A major shortcoming of the MDGs was the failure to clearly spell out the resources required for implementation. The latest proposals for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) attempt to do so more comprehensively, in a more meaningful spirit of partnership. But will these proposals survive, and who will be monitoring?

by Debapriya Bhattacharya and Mohammad Afshar Ali

Following a protracted inter-governmental consultation through the Open Working Group (OWG) in New York, the UN began moving in July 2014 into the negotiation phase of setting the post-2015 development agenda. In addition to proposing new goals and targets, these discussions have included the means of implementation (MoI) to achieve the SDGs.

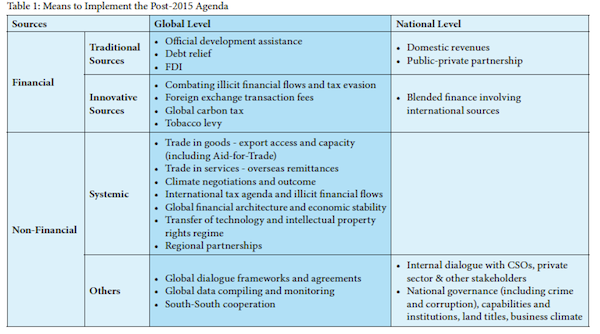

MoI may be presented as two broad sets of modalities and instruments. First, the means of implementation could be distinguished from the perspective of key instruments: financial and other (non-financial). Second, they may be considered from the perspective of jurisdiction or level of operation: global and national policies and institutions, although some may be regional. Experience has shown that the effectiveness of financial MoI is reduced significantly in the absence of complementary policy and institutional measures, particularly global ones.

The final outcome document of the OWG has proposed a total of 17 SDGs, including proposed goal #17, “Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development.” Comprised of 19 targets to measure MoI, there are another 24 targets related to MoI that appear earlier for goals #1 to #16. However, a number of potential MoI are missing in these targets, including mobilization of innovative finance (e.g. foreign exchange transaction fees, carbon tax) and blended finance.

A depiction of these MoI is shown in Table 1, and the different instruments and levels of operation are outlined in greater detail in this briefing paper.

Institutional Arrangements for Delivering the MoI

With the rise of the global South, the role of South-South cooperation (SSC) is increasingly finding pride of place as an MoI within discussions of a viable “global partnership” for the realization of the post-2015 agenda. The first high-level meeting on the Global Partnership on Effective Development Cooperation (GPEDC) took place in Mexico in April 2014. Traditional donors are changing their emphasis from “aid effectiveness” to “effective development cooperation” with a view to including “new” actors (e.g., from the private sector and new donors from South) as well as to expanding the tool box of cooperation (e.g., private public partnerships and corporate social responsibility funds).

The large Southern countries are gradually increasing their role as nontraditional donors and may increasingly define the global economic landscape and help ensure the delivery of the post-2015 agenda. SSC will thus be both about financial resources and other means of implementation. Given that many of these countries enjoy economic surpluses and reservoirs of knowledge, expertise, and technology, they are naturally positioned to become providers of resources to poorer developing countries.

Conclusion

The adequacy of the MoI for the post-2015 agenda can be best assessed once the agenda itself is adopted. It would be desirable to develop a matrix of tasks and responsibilities for each of the goals and targets (and perhaps the indicators too). Each target should be agreed along with a clear idea about delivery mechanisms.

In this connection, accountability and monitoring should be an integral MoI. The MDGs had no specific framework to mobilize additional resources—other than to reiterate the 0.7 percent ODA target—which was a major shortcoming in the exercise.

The ongoing disagreements about the content and packaging of the goals and targets reflects a continuing reluctance by countries with means—be they from the North or the wealthier parts of the South—to commit resources to the post-2015 development framework or to an accounting and monitoring mechanism with independence and teeth to keep commitments under review.

Ultimately, the most important means of implementation will be the political will of global leaders, which hopefully will be reflected in the “Declaration” in the final document. The global public’s vigilance should seek to keep the feet of political leaders to the fire by constantly reminding them of their commitment to end global poverty and “leave no one behind.”

Debapriya Bhattacharya is Distinguished Fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) in Dhaka and chairs Southern Voices on Post-MDG International Development Goals. He is the former ambassador and permanent representative of Bangladesh to the WTO and UN Offices of Geneva and Vienna, and the special advisor on LDCs to the secretary-general of UNCTAD.

Mohammad Afshar Ali is Research Associate at the Center for Policy Dialogue (CPD) in Dhaka. His undergraduate and graduate degrees are from Jagannath University, Dhaka; his current areas of research are macro-economics and post-2015 development issues.