Published in on Wednesday 15 May 2019

BJMC burdened with losses

Anomalies in jute purchase, low productivity, inefficiency key factors; Tk 7,477cr bailout in last 10 years fails to improve situation

Sohel Parvez

The Bangladesh Jute Mills Corporation (BJMC) appears to be a bottomless pit. Over the past decade, the government handed it Tk 7,477 crore to bail it out of its financial troubles, and yet it has put its hand out for more.

The Bangladesh Jute Mills Corporation (BJMC) appears to be a bottomless pit. Over the past decade, the government handed it Tk 7,477 crore to bail it out of its financial troubles, and yet it has put its hand out for more.

It has sought Tk 337 crore to clear arrear wages until June of its 32,740 workers and employees.

“If we get the fund, the ongoing labour unrest will be over,” said BJMC Chairman Shah Muhammad Nasim, adding that it is likely to seek an allocation of Tk 1,600 crore to implement the 2015 wage scale for its workers.

And yet, the corporation, which comprises of 22 jute mills and 3 non-jute mills, is nowhere near to standing on its own feet.

Corruption, inefficiency, dated technology, presence of ghost workers and an absence of competitive zeal and work-shyness amongst a section of the employees have been blamed for the sorry state of the mills.

This coupled with the shrinking demand for traditional jute goods around the globe means losses have become a permanent feature of the BJMC, the largest state corporation.

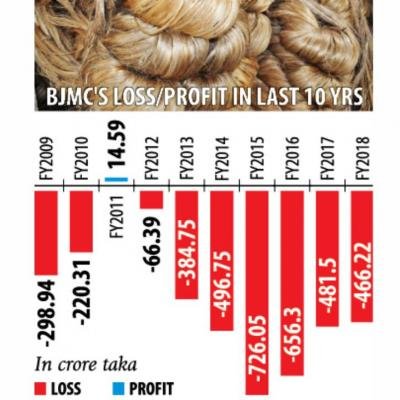

Save for fiscal 2010-11, it has not turned in any profit or broke even in any year since early ‘80s.

In the first nine months of this fiscal year, its losses stand at Tk 495 crore, which has already overshot last fiscal year’s losses of Tk 466 crore.

PURCHASE OF JUTE AT HIGHER PRICES

The BJMC mainly purchases relatively inferior grades of jute at higher quantities to make jute goods.

Roughly, it buys 30 percent jute of relatively better grade jute tosa C-grade, 41 percent cross-bottom (medium quality) grade and 15 percent low-grade SMR category of jute. Other types of jute make up the remaining 14 percent, said BJMC General Manager Mohammad Mohiuddin Sadek.

Its overall purchase price though tends to be higher than the average wholesale price of raw jute.

For instance, in fiscal 2015-16 it bought one quintal (100 kilogram) of raw jute at Tk 4,819. But the average wholesale price of one of the best quality jute (white/top tosa) was Tk 4,416 per quintal then, according to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS).

Its purchase the following year followed the same pattern: it had bought one quintal of jute for Tk 4,713, when the average wholesale price of white/top tosa was around Tk 4,000.

Sadek blamed the discrepancy on the cuts taken by middlemen. “Such situation occurs when we cannot buy during the peak harvesting season for fund shortage,” he said.

However, in its audit for fiscals 2011-12 and 2012-13, the Comptroller and Auditor General of Bangladesh (CAG) found anomalies in jute purchase by a section of BJMC officials.

There is involvement of various interest and vested groups in jute purchase at the local level, due to which quality jute cannot always be purchased at the fair market value, according to Nasim.

LOW PRODUCTIVITY

Out of 10,835 looms, 4,452 looms in mills under the BJMC are in operation. However, productivity is falling as the mills are run with old machinery, which were mostly bought before the liberation of Bangladesh.

And no modernisation took place since then.

Subsequently, the efficiency of BJMC mills is now below 50 percent, it said.

“The BJMC will never be able to sustain with its existing machineries,” said Shahidullah Chowdhury, a veteran labour leader of the jute sector, adding that all its machineries have to be upgraded to cut down on production costs and improve productivity.

This may lead to a reduction in the number of workers but the BJMC will be able sustain, he said.

HIGHER PRODUCTION COST

The BJMC data showed that its production cost has been rising over the years. But, its production was declining.

The BJMC data showed that its production cost has been rising over the years. But, its production was declining.

For instance, in fiscal 2010-11, the corporation produced 1.66 lakh tonnes of jute goods at Tk 90,201 per tonne. In fiscal 2017-18, it churned out 1.32 lakh tonnes but at Tk 126,286 each tonne — up 40 percent in seven years.

BJMC officials blamed the falling productivity of machineries and higher wages than their counterparts at private mills for the spiralling production costs.

In 2010, the corporation implemented the government-announced national wage scale for workers in state-owned mills, which was — higher than that of private mills.

Under the 2010 wage scale, it has to pay Tk 4,150 as minimum wage, in contrast to Tk 2,700 at private jute mills.

The production cost will soar more once the corporation implements the national wage scale 2015 that fixed Tk 8,300 as the minimum wage for state-mill workers.

To implement that from July, a proposal will be forwarded to the government for allocation in the budget for fiscal 2019-20.

“The government itself has announced the new wage scale. If it wants to run the BJMC, it should allocate the fund in the budget. There is no alternative to this,” he added.

Khondaker Golam Moazzem, research director of the Centre for Policy Dialogue and a keen follower of the jute industry, said the BJMC would be unable to sustain the increased wages given its continuing losses.

SALES BELOW PRODUCTION COST

While the BJMC’s production cost rose 40 percent, it hiked the overall prices of jute goods by 11 percent to Tk 95,713 per tonne during the period.

The corporation increased the export price by 9 percent in the seven years to Tk 86,545 per tonne in fiscal 2017-18. And over at home, it sold one tonne of jute goods at Tk 128,020 in fiscal 2017-18, up 11.57 percent from seven years earlier.

And yet its sales prices at both home and abroad since fiscal 2010-11 have been below its production cost.

Falling export

Despite selling jute goods at much below its production cost in the global market, the BJMC has been registering falling exports.

Despite selling jute goods at much below its production cost in the global market, the BJMC has been registering falling exports.

The corporation’s shipment tumbled to 86,740 tonnes in fiscal 2017-18 from 2.23 lakh tonnes in fiscal 2000-01. Its exports, both in terms of value and volume, nosedived further — 79 percent year-on-year — in the first six months of fiscal 2018-19.

India, Sudan, Thailand, Iran and Syria were the top five markets for the BJMC’s jute goods in fiscal 2012-13. Save for Sudan, it has been witnessing falling exports in all.

The BJMC’s shipment to India, Syria, Iran, Egypt and Indonesia slumped to 13,301 tonnes in fiscal 2017-18 from 49,407 tonnes in fiscal 2015-16.

In its annual report for fiscal 2017-18, the BJMC said it has become tough to fix competitive prices for jute goods thanks to its high production cost as a result of increased wages and declining efficiency of machines.

The fast-declining efficiency of machines has also emerged as a stumbling block for the state mills in ensuring timely delivery and meeting the requirements of buyers, it said.

Apart from these problems, its export market squeezed further since fiscal 2016-17, when India slapped anti-dumping duty on jute goods on allegation of selling sacking bags to Indian buyers below the domestic market prices.

In the subsequent year, the BJMC’s exports to India tumbled to 8,987 tonnes from 48,140 tonnes in fiscal 2012-13, its data showed.

CPD’s Moazzem said the BJMC also faced anti-dumping duty in the past from Brazil.

“The BJMC’s pricing of jute goods severely affects the domestic and international markets,” he said, while recommending the state corporation to revisit its pricing policy for both the domestic and export markets.

Inadequate local sales

The BJMC data showed that its sales of jute including sacking bags rose to 44,320 tonnes in fiscal 2015-16 owing to enforcement of mandatory jute packaging law by the government.

Its domestic sales, however, slumped to 25,418 tonnes in fiscal 2017-18.

“Our losses will be reduced to a large extent if our local demand increases,” the BJMC chairman said.

As a result of low sales in both the domestic and international markets, the BJMC was sitting on heaps of hessian, sacking and other jute goods, the value of which is Tk 755 crore until January this year, according to its estimate.

Lack of professionals in the management

Apart from this, lack of experience of top management officials is another reason behind the BJMC’s poor performance.

The management, chairman and directors are usually brought in from civil service to run the organisation, meaning they do not have substantial experience and knowledge of the industry, said insiders.

“The majority of the officials at the decision-making level were deputed from other departments. This caused serious problems in a corporate entity,” Moazzem said.

Besides, most of the senior officials stay here for less than one year. “In corporate standards, it is not acceptable. It creates a situation of lack of accountability and fosters inefficiency,” he added.

In a note on BJMC in July 2015, former finance minister AMA Muhith blamed the weakness in government’s management for the poor condition of the state mills.

“The burden of losses will only rise if funds are given without changing the existing system of management,” he said.

Payment to ghost workers

Industry insiders also blamed the presence of ghost workers in state mills for its high operating costs.

For instance, in its fiscal 2011-12 audit report, the CAG found payment of an additional Tk 2.28 crore as wages to workers by wages in-charge and cashier of Carpeting Jute Mills.

Way out?

BJMC Chairman Nasim said the losses have accumulated overtime and it is not possible to turn the organisation into profits soon.

“A detailed analysis is necessary,” he said.

He also blamed the staggered release of funds by the government for many of its current failings.

“If the fund is given in one go, a lot can be done. Our problem is that we get lesser amount than what is needed. As a result, we again fall into deficit.”

Subsequently, he called for an endowment fund such that the corporation’s operational costs such as wages and raw jute purchase could be met with the fund’s interest income.

Asked why would the government should bail out the corporation with taxpayers’ money, he said that 4 crore people are dependent on the jute industry for their livelihoods and the BJMC’s existence is also necessary for ensuring fair prices for jute growers.

But CPD’s Moazzem disagreed. Public sector jute mills were necessary for industrialisation and job creation in the 1960s, 1970s and partly in the 1980s.

“But the importance of state capital industrialisation has changed. The role played by the BJMC is no more necessary. The private sector has developed enough to ensure industrialisation,” he said, suggesting gradual reduction in BJMC’s operation.

Workers’ leader Shahidullah called for immediate downsizing of certain departments of the corporation. “It should also curb unnecessary expenditures. There is a need for BJMC, but reforms have become urgent.”