Dr Fahmida Khatun examines some key issues related to special and differential treatment for LDCs, published in Dhaka Tribune on Sunday, 1 December 2013.

Why and what S&D Treatment for LDCs?

Dr Fahmida Khatun

Examining some key issues related to special and differential treatment

The ninth Ministerial Conference of the World Trade Organization (WTO) is around the corner. The conference of the trade ministers of the WTO member countries to be held in Bali during December 3 -6 is being organised in the background of very low expectations.

There has been little progress of the Doha Round negotiations which was initiated in 2001. Progress on major agreements such as agriculture, non-agricultural market access and services has been insignificant and partial.

However, optimists are looking forward to see some outcome in a few areas including trade facilitation agreement and development issues that include LDC package and special and differential treatment (S&DT). However, there are problems too. This article will examine some key issues related to S&DT for least developed countries (LDCs).

Given that trade liberalisation does not automatically lead to development and welfare gains for all countries as they cannot take advantage of opportunities created by trade liberalisation due to lack of capacity, the relevance of S&DT for LDCs cannot be overepmhasised.

S&DT describes preferential provisions in various agreements of the WTO for developing and least developed countries. This is in view of major bottlenecks these countries face in taking advantage of the global trading systems. It is widely recognised that due to several supply side bottlenecks developing countries, particularly LDCs, are unable to participate effectively in the multilateral trading system.

In view of marginalisation of weaker economies in the context of globalisation, lack of technical capacity, lack of financial resources, and weak capacity to take advantage of the opportunities emanating from the WTO system developing countries and LDCs were given flexibility by the multilateral trading system.

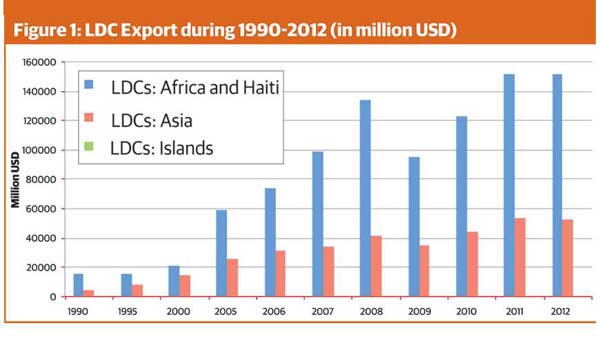

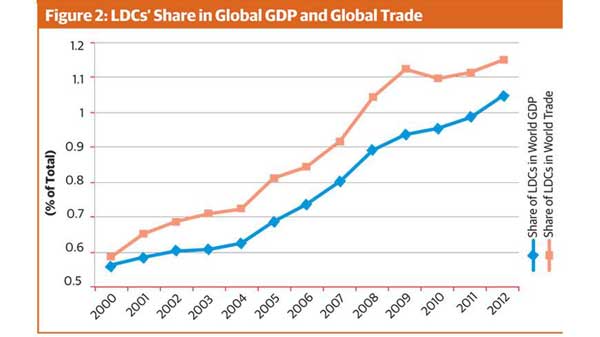

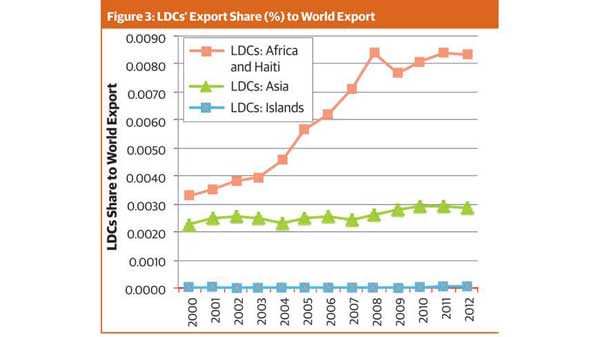

Though LDCs’ participation in global trade has increased over the years (Figures 1 and 2), the distribution of growth has not been equal across regions. At present, LDC group consists of around 12% of world population.

However, LDCs have a share of little over 1% in world GDP while they account for about 1% of global trade in goods (Figure 3). Moreover, there are some inherent weaknesses in the structure of export from LDCs.

First, LDCs have a narrow export basket. In 2011, seven oil and readymade garments exporting LDCs accounted for a lion’s share of 68.4% of total exports from LDCs. In case of Bangladesh, RMG’s share was 82.65% and in case of Angola fuels and oil contributed to 97.42% of total export income.

Second, LDC exports are overwhelmingly dependent on primary products. And because of high commodity prices, LDCs earned higher export income indicting that LDCs’ higher export is due to increase in the value of commodities rather that volume.

Brief overview of S&DT provisions

Trade negotiations under the auspices of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) supported the S&DT to developing countries. This continued after the formation of the WTO which is reflected through and also upheld the principle of providing special treatment to developing countries.

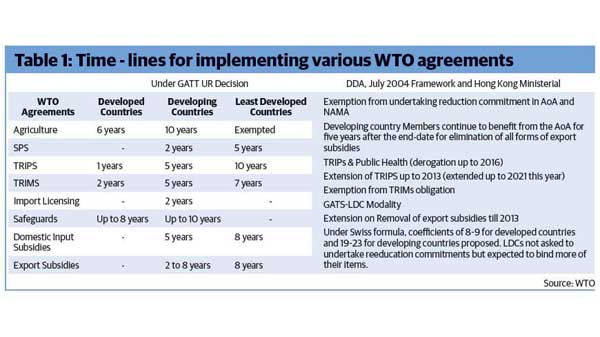

Article XVIII of GATT recognised the need for additional flexibility and introduced for the first time the concept of differential treatment of developing countries. The S&D provisions for LDCs include: (i) longer time periods for implementing agreements and commitments; (ii) measures to increase trading opportunities; and (iii) support to help LDCs build the infrastructure. These measures are reflected through various WTO agreements which can be summarised in Table 1.

During the Doha Ministerial of the WTO in 2001, Members reaffirmed that the provisions for S&DT are an integral part of the WTO agreements. Paragraph 44 of the Doha Mandate (2001) says: “We note the concerns expressed regarding their operation in addressing specific constraints faced by developing countries, particularly least-developed countries. In that connection, we also note that some members have proposed a Framework Agreement on SDT (WT/GC/W/442). We therefore agree that all SDT provisions shall be reviewed with a view to strengthening them and making them more precise, effective and operational. In this connection, we endorse the work programme on SDT set out in the Decision on Implementation-Related Issues and Concerns.”

At the Cancun Ministerial 2003, members included 28 agreement-specific S&DT provisions in the Annex C of draft ministerial text. Eventually these provisions were not adopted due to the conference’s failure to agree on a number of other issues.

Members agreed to five S&DT provisions for LDCs at the Hong Kong Ministerial (2005). These include: DFQF (duty-free quota-free) access by 2008; preferential rules of origin (RoO); right to undertake measures for their development; trade preferences not be conditional loans, grants and ODA inconsistent with LDCs development; allowed to deviate from obligation in the TRIMS agreements.

The Geneva Ministerial Conference in 2011 (MC8) provided extension of preferential treatment for service trade for another 15 years. A “Draft Decision” on the expansion of TRIPS transition period. Some ministers suggested the review and monitoring of S&DT provisions in the WTO. It may be mentioned that on June 11, 2013, LDCs have been granted up to July 1, 2021 to implement TRIPS Agreement.

At the Geneva Ministerial Meeting, ministers agreed to expedite work towards finalising the monitoring mechanism for S&DT provisions. Ministers agreed to take stock of the 28 Agreement-specific proposals in Annex C of the draft Cancun text with a view to formal adoption of those agreed.

Current state of play

In view of LDCs’ demand for an outcome in the S&DT provision discussions are being held at the WTO on two important aspects during the run up to the Bali Ministerial Conference in December 2013, namely (i) adoption of 28 S&D provisions; and (ii) monitoring mechanism.

WTO Members never formally adopted 28 proposals relating to various S&D provisions in WTO agreements proposed in Cancun though the eighth WTO Ministerial Conference agreed to take a stock of these proposals. Since those proposals were adopted in 2003, developments in the ministerial meetings after Cancun possibly have affected the relevance of some texts in the provisions.

Hence, it is felt by many members that there is a need to revise some of the texts. For example, the text on market access or LDCs should incorporate DFQF decisions taken in the Hong Kong Ministerial.

On monitoring mechanism, discussions are being held at the special session of the Committee on Trade and Development for an appropriate monitoring mechanism. The purpose of such monitoring is to analyse and review the implementation of all S&D provisions contained in WTO agreements and decisions.

Though this is not only limited to LDCs, the adoption of such a mechanism is expected to have positive implications for LDCs. Such mechanism will provide opportunities for LDCs to raise issues and flag difficulties faced by them in implementing S&D provisions.

Way forward

At the core of the implementation of S&D provisions is the issue of implementation of DFQF market access for LDCs. Meaningful and enhanced market access for LDCs remains to be an unfulfilled agenda. Several studies have estimated the benefit of DFQF market access.

It has been found that effective market access of LDCs after S&DT in the USA is negative and in the EU is positive but negligible because of 3% of tariff lines excluded from DFQF market access that make up a significant share of LDCs exports (Carrere and de Melo 2009). On the other hand, DFQF access for LDCs from 97% to 100% of tariff line will increase LDCs export to developed countries by $4.2 billion (Vanzetti and Peters 2012).

Related to market access is the issue of preference erosion. Currently, many LDCs benefit from non-reciprocal preferences granted mostly by developed countries. As liberalisation intensifies, LDCs will lose out on this as their preferences margins will erode. In order to compensate LDCs which suffer from preference erosion, there should be financial support to LDCs.

Meaningful market access requires preferential RoO that are transparent and simple. There has been some progress on this. Canada, the EU and Switzerland have adopted revised RoO criteria that have positive impact on LDC exports. Other countries also need to adopt liberal RoO.

Operationlisation of “Development” provisions of the Doha Development Agenda depends, in many ways on the implementation of S&DT provisions. However, many of the WTO agreements as regards S&DT are operationally problematic for at least two reasons.

First, many provisions are of “best endeavour” nature. The African group and the LDCs emphasised for 88 agreement-specific proposals for S&DT enhancement. Only 38 provisions that related to modulation of commitments are legally binding while 50 provisions on trade preferences and declaration of support are not. So there is a need to develop an approach that defines clear and concrete rights and obligations for all members.

Second, many current S&D provisions are also of “one size fits all” nature. This notion ignores the fact that development challenges faced by the WTO members are varied and therefore cannot be addressed by uniform rules. Thus, there is need for specifying rights and obligations of members for implementing S&D provisions.

Unfortunately, discussions during the run up to the Bali WTO Ministerial Conference have not led to any clarity on the work programme as regards the implementation of agreed proposals by the developed countries. Therefore, LDCs will have to continue to pursue the issue during the post-Bali period.