Originally posted in The Daily Star on 27 March 2024

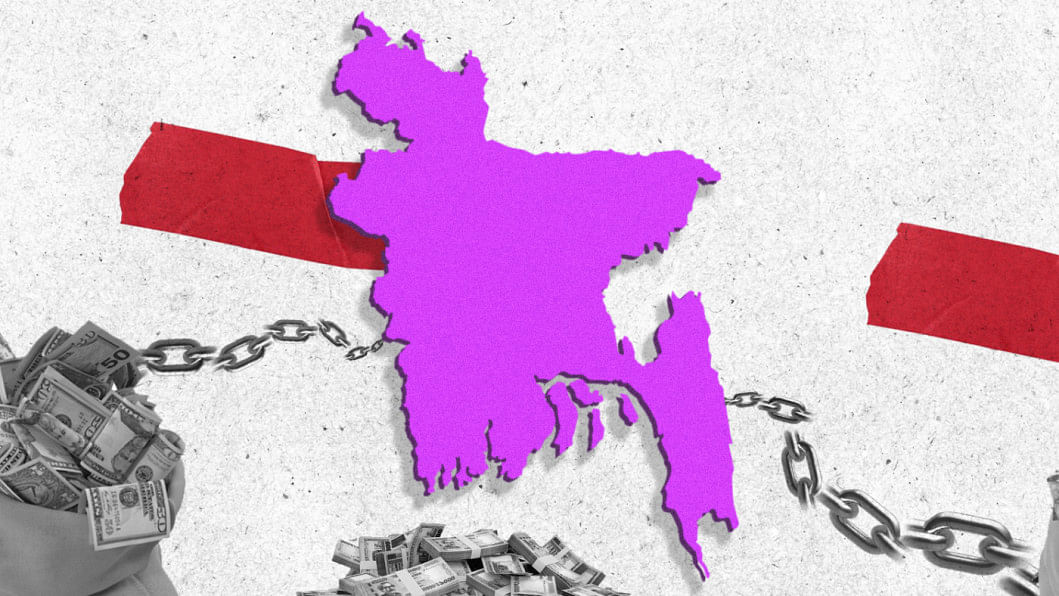

Recently, Bangladesh’s external debt situation has become a topic of discussion—and for several reasons. While Bangladesh’s external debt is deemed comfortable according to the IMF’s Debt Sustainability Report (November 2023), there are concerns about the significant increase in debt servicing liabilities. Due to high interest expenses, a larger share of non-concessional loans in the borrowing portfolio, and stricter loan conditions imposed by the lenders, the burden of foreign loans is increasing. The mounting debt servicing obligations also threaten to exacerbate the strain on the country’s low foreign exchange reserves.

In December 2023, external debt in Bangladesh reached $100.6 billion. Of this, the share of public sector debt was 79.2 percent, while that of the private sector was 20.8 percent, as per the data from the Economic Relations Division (ERD). The increase in external debt from December 2022 to December 2023 is 4.3 percent.

The debt-to-GDP ratio in Bangladesh has been steadily increasing over the past few years. In June 2023, external debt constituted 15.9 percent of the GDP, compared to 13.2 percent in FY2016 (Flow of External Resources into Bangladesh, ERD, 2024).

Several other pertinent indicators paint a concerning picture of Bangladesh’s external debt situation. For instance, the ratio of external-debt-to-exports surged from 56.3 percent in FY2016 to 116.6 percent in FY2023. The change in debt-to-exports highlights slower export growth compared to the increase of external loans, exacerbating the nation’s debt burden. The escalating external-debt-to-exports ratio is disquieting as it implies that there may be a shortfall in resources to meet forthcoming repayments. The ratio of external debt to revenue collection has risen from 133.3 percent in FY2016 to 192.3 percent in FY2023. This underscores the pressing need for increased revenue generation. With high demand for foreign loans due to infrastructural gaps, Bangladesh faces a heightened dependency on both domestic and external borrowings. However, with the tax-to-GDP ratio remaining around eight percent, the government’s constraints on development spending from domestic sources highlight the necessity for higher external borrowing.

Another feature of external debt is that since the amount of external borrowing is increasing, the external debt outstanding has witnessed significant increase. For example, the external debt outstanding has gone up from $26.3 billion in FY2016 to $62 billion in FY2023. This is concerning since the amount of money borrowed and the amount that needs to be repaid exceeds the amount of debt Bangladesh has serviced.

With the growth in external debt, repayment of foreign loans has also surged, escalating from approximately $3 billion in FY2013 to $4.78 billion in FY2023, marking a 59.3 percent increase over a decade. Given exchange rate fluctuations and the potential for further interest rate hikes on foreign loans, the repayment amount could increase even more.

Since Bangladesh made a transition from a low-income country to a lower-middle-income country in 2015, according to World Bank’s criteria based on per capita income, the terms and conditions for borrowings from the World Bank have changed. This has also been the case for other lenders including the Asian Development Bank (ADB), Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and Japan International Cooperation Agency (Jica). Indeed, the World Bank and ADB’s interest rates are up from one percent to two percent, while that of Jica has gone up to 1.6 percent, which used to be lower than one percent. The proportion of non-concessional loans in the portfolio has been steadily increasing. Borrowing conditions are becoming stricter, characterised by reduced grace periods and maturity periods, as well as additional fees and service charges.

Besides, Bangladesh has obtained certain foreign loans tied to adjustable London Inter-Bank Offered Rate (LIBOR), which has now been replaced with Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR). In recent years, there has been a noticeable rise in these rates. For instance, the SOFR currently stands at over five percent—a significant increase from its previous level of under one percent. Therefore, clear signs of an impending increase in the country’s debt servicing liabilities in short and medium terms are visible.

Another concern arises from the existing problems of low forex reserves and a volatile exchange rate. Bangladesh may face hurdles in effectively managing its debt servicing in the forthcoming years, especially considering the ongoing decline in forex reserves. The government should therefore plan effectively when pursuing foreign borrowings. This entails reducing reliance on loans with stringent conditions, prioritising foreign-loan-funded projects, and ensuring efficient governance in implementing publicly funded projects.

Bangladesh’s economic trajectory has been on a tumultuous path since the onset of the pandemic. FY2024 continued to reflect this trend. While economic resilience contributed to growth for a long time, the economy is currently going through difficulties in the form of high inflation, declining forex reserves, volatile exchange rate, insufficient revenue collection, and limited investment. The combination of high growth and low inflation enjoyed by the country for a long time is now gone. Amid these adversities, the prominence of external debt and its servicing liabilities sends us a cautionary signal.

Given the current situation, a judicious repayment strategy and structural reforms are required to effectively mitigate the pressure of foreign debt repayment. Indeed, prudent management of the overall debt situation is needed—both domestic and external—in view of Bangladesh’s emerging external debt landscape. Reforms of the relevant institutions responsible for performing crucial tasks such as revenue generation, public expenditure, and project implementation are critically important.

Dr Fahmida Khatun is executive director at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) and non-resident senior fellow of the Atlantic Council. Views expressed in this article are the author’s own.

Views expressed in this article are the author’s own.