Originally posted in bu.edu on 16 April 2024

By Jwala Rambarran and Fahmida Khatun

Developing countries require considerable capital investments to accelerate the shift to low-carbon economies, enhance resilience to climate shocks, address loss and damage, restore biodiversity loss and navigate the cross-border spillovers associated with the global climate transition.

Estimates of these external financing needs converge around $1 trillion per year by 2030, which are well beyond the restricted fiscal capacities of many developing countries, especially those with high and rising debt that further constrains their borrowing space and debt sustainability prospects. International cooperation is therefore essential to help these countries urgently unlock and mobilize substantial and affordable financing to achieve a just, global climate transition.

As the only multilateral, rules-based institution responsible for promoting macroeconomic and financial stability, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has a central role to play in the transition to a low-carbon and resilient global economy. In this respect, the IMF took an important step to expand and complement its lending toolkit by creating a new instrument, the Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST).

The RST is designed to provide longer-term, concessional financing to low-income countries, small developing states and vulnerable middle-income countries to help them reduce the risks to prospective balance of payments stability, including those stemming from key structural challenges such as climate change and pandemic preparedness. The IMF’s Executive Board approved the RST in April 2022, and it became operational in October 2022.

Costa Rica, Barbados, Rwanda, Bangladesh and Jamaica were the first five countries to access financing from the RST under the Resilience and Sustainability Facility (RSF), the instrument through which the IMF makes RST loans available to its members. At the end of March 2024, the number of RSF programs had grown to 18, well below the average of 33 active RSF programs a year that the IMF had initially estimated. All these arrangements focused exclusively on climate change; the IMF’s Executive Board has yet to approve RSF programs focused on pandemic preparedness.

Going forward, the key question is how can the IMF ensure that the RST addresses a major gap in the global financial architecture, namely balance of payments support for climate shocks and green transitions to foster resilient and sustainable growth over the medium-term?

Based on the initial experiences of some of the pilot countries accessing RST financing, a new policy brief from the Task Force on Climate, Development and the IMF offers recommendations for the design of future RST loans to ensure they adapt to the specific and unique circumstances of the IMF membership and the urgent need to address the climate crisis.

Policy recommendations for a stronger RST

The policy brief takes stock of the early experiences of three climate vulnerable countries – one developing country in Asia (Bangladesh) and two emerging market economies in the Caribbean (Barbados and Jamaica) – in accessing concessional RST financing, and it evaluates the climate conditionality and potential catalytic financing impact of the three RSF programs.

The brief identifies five areas where the IMF should show greater leadership to strengthen the RST so that it aligns with a more development-centered approach to climate change: expanding resources, eliminating concurrent programs as a key requirement, aligning RST program design with ambitious climate and development polices, emphasizing a focus on catalyzing finance for maximum impact and institutionalizing collaboration with the World Bank.

EXPANDING RESOURCES

The RST is currently capitalized at $40 billion but usable resources stand at about $25 billion, accounting for buffers that are built into the RST. Given both the demand of the RST and the unprecedented scale of financing need to meet shared development and climate change goals, replenishment through re-channeled Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), the Fund’s reserve asset, will be vital in the next five years. Furthermore, financial resources alone will not be enough; the RST will also require the human resources to support and execute a high-quality program design.

ELIMINATING THE REQUIREMENT FOR A CONCURRENT IMF PROGRAM

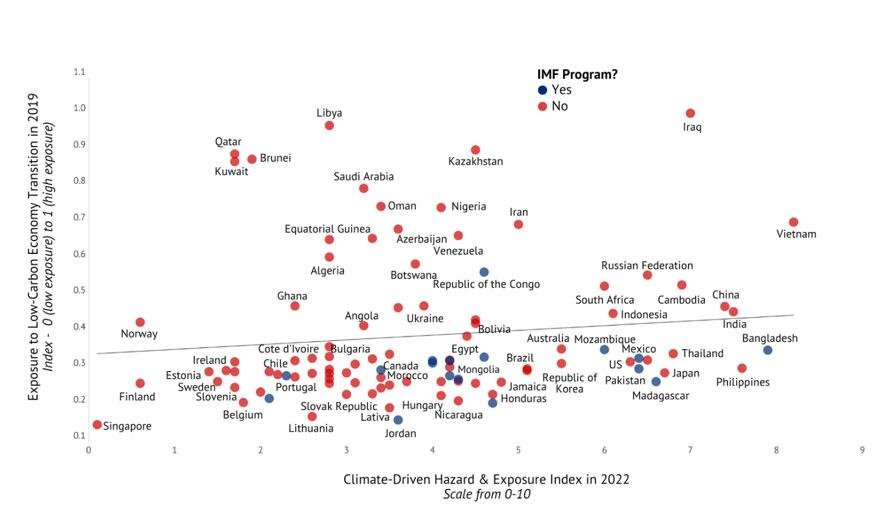

To qualify for RST financing, eligible countries need, among other things, to have a concurrent on-track financing or non-financing IMF-supported program with “upper credit tranche” quality policies and at least 18 months remaining in the program at the time of approval of the RSF arrangement. However, such a requirement restricts members’ access to the RST. Figure 1 shows, as of April 2023, if countries facing climate vulnerability have an IMF program, revealing overwhelmingly that this is not the case.

Figure 1: Climate Vulnerability and IMF Programs

Source: Task Force on Climate, Development and the IMF (2023) from Ramos, L. (2023); Data source: IMF and World Bank (2023).

The qualifying requirement is also reducing the overall effectiveness of the push to re-channel SDRs. The RST is funded through voluntary rechanneling by the Group of 20 (G20) countries as part of the IMF’s 2021 historic allocation of SDRs. Going forward, it is essential for the IMF to remove the requirement to have a concurrent Fund program.

ALIGNING PROGRAM DESIGN WITH AMBITIOUS POLICIES

As it stands now, the policy brief shows that Barbados and Jamaica in particular see a substantial increase in conditionalities. However, as shown in Table 1, the conditions in IMF RSF programs are predominantly low-depth reforms which, in themselves, do not bring about a change but can pave the way for implementation of more critical reforms. This means that RSF arrangements are not tackling longer-term structural reforms, despite these countries having ambitious nationally determined contributions and adaptation strategies.

Table 1: Depth of Structural Conditions in IMF RSF Programs

| Country | Low | Medium | High | TOTAL |

| Bangladesh | 10 | 1 | 0 | 11 |

| Barbados | 4 | 5 | 1 | 10 |

| Jamaica | 6 | 6 | 0 | 12 |

| 20 | 12 | 1 | 33 | |

Source: Task Force on Climate, Development and the IMF 2024.

To that end, RSF arrangement conditions should align with and add momentum behind ambitious climate and development policies.

In designing future RSF arrangements, particularly in highly indebted, climate-vulnerable countries, the IMF should consider deploying more RST resources to create fiscal space for climate action through debt relief solutions that are timely, fair and effective. This could be done by linking debt relief options such as debt pause clauses, debt restructuring and reprofiling, and debt swaps to investments in green resilience policies aligned to a country’s national climate and development plans.

More generally, affordable and accessible liquidity support arrangements are crucial to ensuring that countries can manage short-term shocks. The high cost of borrowing faced by emerging market and developing economies makes the provision of low-cost financing urgent. The G20 should tackle this directly by issuing a new round of SDRs to help countries cope with liquidity challenges and increase the supply of concessional finance.

CATALYTIC ROLE

RSF arrangements have an overwhelming reliance on the IMF’s catalytic effect to unlock external financing for investments in climate mitigation and adaptation, even though there is limited empirical evidence to justify this catalytic role. The potential of private finance to help close a country’s climate financing gap is compelling, but the RSF’s catalytic character in making this happen is still unproven.

Early RSF country experiences demonstrate that the signaling effect of climate policy reforms to spur large-scale private climate investments faces strong headwinds. At the end of 2023, both Barbados and Jamaica had not attracted any private climate finance flows, despite having an RSF arrangement for 12 months and nine months, respectively. Bangladesh received a marginal amount of private climate financing.

Programmatically, the IMF can have RSF arrangements play a much stronger catalytic role in mobilizing private climate finance through a focus on a few ambitious, high-depth policy reforms that stand a reasonable prospect of successfully generating transformational change or having a long-lasting impact. This shift may encourage the private sector to come to the table.

INSTITUTIONALIZING WORLD BANK COLLABORATION

Catalytic structural conditions would also require the IMF to closely engage with the World Bank and other regional multilateral development banks (MDBs). The World Bank’s deep sectoral expertise can provide the analytical foundations to design material RSF policy reforms. To this end, the IMF should institutionalize its climate collaboration with the World Bank. This collaboration could also allow the IMF to leverage the human resources of the World Bank. High quality program design will require the IMF to have access to the necessary expertise. Furthermore, closer collaboration with the World Bank could also help increase the catalytic impact of the RST. The design of country platforms requires the involvement of development finance institutions.

These policy recommendations from the Task Force not only suggest ways in which the IMF can strengthen the RST, but they are also relevant for IMF member countries wishing to access concessional RST financing through RSF programs.

In a recent keynote speech at Kings College, Cambridge – where John Maynard Keynes, one of the founders of the Bretton Woods institutions, studied and worked – the IMF’s Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva stated that Keynes provided a framework, a “multilateralism for the 20th century,” that served the global community well. Now, it must be updated for a new era.

The IMF has a central role in helping to create this 21st century multilateralism framework by fostering a globally coordinated transition to a low-carbon, climate resilient pathway. It has taken important steps forward in creating the RST, but as this policy brief demonstrates, the IMF must show faster and bolder leadership to make the RST an important, transformational part of the global financial architecture.

*Never miss an update: Subscribe to the newsletter from the Task Force on Climate, Development and the IMF.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published as a product of the Task Force on Climate, Development and the International Monetary Fund, a consortium of experts from around the world utilising rigorous, empirical research to advance a development-centered approach to climate change at the IMF. To learn more, visit gdpcenter.org/TaskForce.