BANGLADESH’S GRADUATION FROM THE LDC GROUP: PITFALLS AND PROMISES

Mapping out a strategy

This is part four of a series of articles based on the Centre for Policy Dialogue’s (CPD) research on Bangladesh’s graduation out of the LDC group. Read the first, second, third, fifth and final parts.

Mustafizur Rahman and Estiaque Bari

Bangladesh has become eligible for LDC graduation at the triennial review of the Committee for Development Policy (CDP) held in March 2018 by meeting the thresholds for graduation: Gross National Income (GNI) per capita, the Human Assets Index (HAI) and the Economic Vulnerability Index (EVI). Bangladesh has been able to satisfy all the three graduation criteria and that also with significant comfort margins.

Bangladesh has become eligible for LDC graduation at the triennial review of the Committee for Development Policy (CDP) held in March 2018 by meeting the thresholds for graduation: Gross National Income (GNI) per capita, the Human Assets Index (HAI) and the Economic Vulnerability Index (EVI). Bangladesh has been able to satisfy all the three graduation criteria and that also with significant comfort margins.

Consequently, Bangladesh’s graduation can claim to be distinct from that of the earlier graduates and the current candidate LDCs. This demonstrates the strength of the economy in making the graduation process a smooth one as the country prepares to finally graduate out of the LDC group in 2024 following two successive triennial reviews in 2021 and in 2024. Against this backdrop, the government of Bangladesh should consider designing an appropriate strategy which will ensure graduation with momentum towards a sustainable graduation.

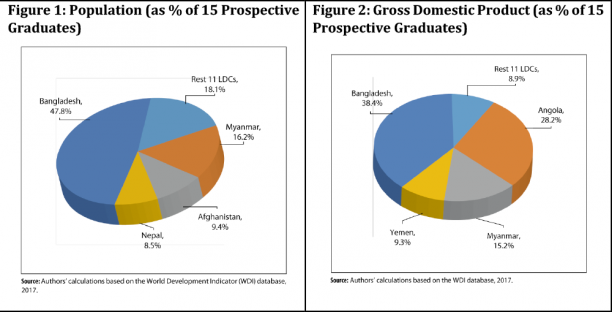

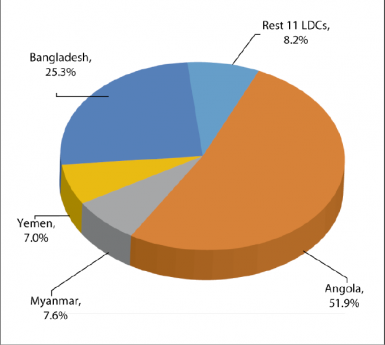

By 2024, 15 LDCs are expected to become eligible for graduation. In this context, Bangladesh will be observed closely for several reasons. First, its graduation would be an irreversible one because of its population size (more than the 75 million threshold). Second, graduation would have greater implications for Bangladesh’s relatively more globally integrated economy compared to most other prospective graduates. Third, Bangladesh stands out among 15 prospective LDCs because of the size of its population and economy.

Fourth, its journey towards graduation is taking place at a time of increasing global uncertainty arising from protectionist threats, stagnation in WTO negotiations, and shifts in global financing modalities. Fifth, graduation would take place at a time when the current highly concessional aid will be gradually substituted by blended and relatively high-cost finance for Bangladesh. Lastly, graduation period will run in parallel with implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Bangladesh. This would require Bangladesh to be more sensitive to environmental concerns and issues of inclusiveness in pursuing its developmental aspirations.

There are about 136 LDC-specific international support measures (ISMs) across the spectrum of trade and market access, development finance, technology transfer and technical assistance. Unless negotiated separately with relevant partners, a large part of these measures would be phased out in 2024. Three implications stand out in this regard.

First, Bangladesh, which accounts for more than one-fourth of total exports from the 15 prospective graduates, would experience significant erosion of preferences. Estimates by the authors indicate that Bangladesh would face additional tariffs of about 6.7 percent in absence of LDC preferential treatment, resulting in a possible export loss of USD 2.7 billion in view of potential earnings (equivalent to 8.7 percent of Bangladesh’s global exports in FY15). Preference erosion would have adverse implications for export competiveness, industrial production and jobs unless compensatory measures are put in place.

Second, Bangladesh’s graduation will parallel its lower middle-income journey. Bangladesh would see a shift from International Development Association (IDA) type of concessional foreign aid to blended and, subsequently, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) type non-concessional finance (with a higher interest rate and more stringent terms and conditionalities).

Third, the country would no longer be eligible for support measures for the LDCs in the WTO. To recall, Bangladesh enjoys a wide range of support in the form of market access, technical assistance and waivers from obligations, protracted implementation periods for obligations and commitments (e.g. Trade Facilitation Agreement), Aid for Trade initiative and other forms of special and differential treatment (S&DT).

Bangladesh’s eligibility for graduation is indicative of its robust record in terms of key macroeconomic and sectoral performance. Crossing the graduation thresholds demonstrates resilience and the underlying strengths of its economy. However, the graduation criteria are only limited to selected indicators, albeit important ones. Graduation with momentum requires energetic efforts towards the needed structural transformation of the economy. In view of the above, what follows are core elements which should inform Bangladesh’s strategy to ensure sustainable LDC graduation.

Reporting requirements as motivation

Between 2018 and 2024, UNCTAD and UN DESA will prepare vulnerability profile and undertake assessments to identify areas that call for close attention from the perspective of Bangladesh’s smooth transition. Bangladesh should take advantage of these reviews, which would help identify vulnerabilities and weaknesses that need to be addressed through its sustainable LDC graduation strategy. The consultative mechanism which would follow LDC graduation should be a good opportunity to seek global support to help the country implement various components of the strategy. Reporting to the CDP and UN ECOSOC should be seen from the perspective of mobilising global support.

Structural transformation

Supply-side diversification and a shift from a factor-driven to productivity-driven economy will continue to be challenging for Bangladesh. The country needs to prioritise policies on technology upgradation, skills endowment, productivity enhancement and increased economic competitiveness. Institutions, incentives and resource allocations will need to be geared towards structural transformation of the economy. In the era of the SDGs, which involve triangulation of economic development, social inclusiveness and environmental sustainability, Bangladesh’s transition will have to be tuned to the attendant aspirations.

Strengthening market access

Bangladesh needs to renew efforts towards supply-side capacity building, increasing export competitiveness and ensuring product and market diversification to compensate for preference erosion and phasing out of international support measures. These efforts should include targeted investment, trade policies for strengthening global integration, trade facilitation measures and mobilising significant foreign direct investment. During the run-up to the LDC graduation, Bangladesh would need to do its best to take maximum advantage of the preferences it is currently enjoying.

Emerging global trading scenario

Bangladesh must pursue strategic trade and industrial policies that will enable it to take advantage of emerging domestic and global opportunities. Proactive partnerships in the context of regional and sub-regional initiatives, including Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor and Bangladesh-Bhutan-India-Nepal Motor Vehicles Agreement, sub-regional energy grid, exploration of the blue economy opportunities, etc., will be needed.

New aid environment

Bangladesh will need to address a number of challenges in view of the newly emerging aid regime: the rising costs of finance, associated increase in external debt, negotiation of access to new financing opportunities, including at the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and New Development Bank (NDB), and raising capital through issuing sovereign bonds in the international market. Negotiating bilaterally with development partners for assistance on favourable terms following the graduation will remain a possibility that should be explored.

Learning from graduated LDCs

Drawing from the experiences of earlier LDC graduates, Bangladesh will need to adequately prepare to reduce specific vulnerabilities, undertake targeted initiatives towards structural transformation of the economy and explore windows of opportunities by proactively engaging with international organisations (e.g. the WTO), multilateral institutions (e.g. the World Bank, the ADB and regional financial entities) and development partners, and calibrate policies in view of emerging challenges (e.g. Brexit). The EU has already agreed to extend Everything But Arms (EBA) for an additional three years for all graduated LDCs (in case of Bangladesh, till 2027). Flexibility concerning preferential treatment should also be explored through negotiations with other development partners and organisations.

Mustafizur Rahman is a distinguished fellow and Estiaque Bari is a senior research associate at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD).

Disclaimer: This blog was earlier Published in The Daily Star on Saturday, 24 March 2018