Originally posted in The Daily Star on 8 February 2024

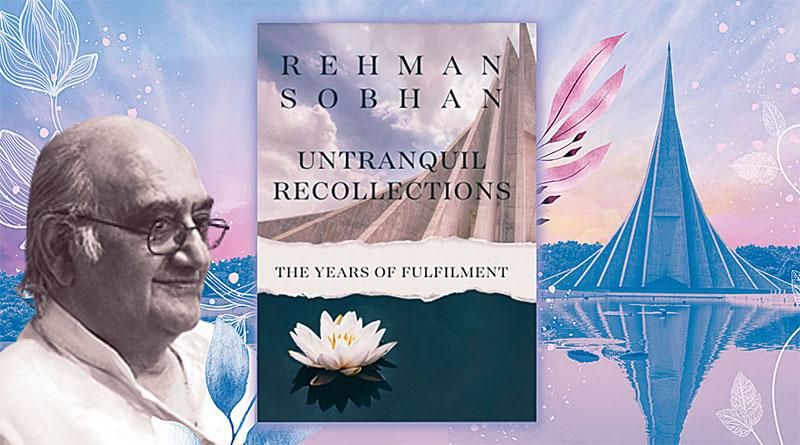

Review of Rehman Sobhan’s ‘Untranquil Recollections: The Years of Fulfilment’ (The University Press Limited, 2024)

The title of the first of Professor Rehman Sobhan’s two-part memoir suggests that it is about his “years of fulfilment”; the subject matter of its sequel therefore would be about the “untranquil” years that followed. If the promised land he arrived at as a 37-year-old man at the end of 1971 was liberated Bangladesh, the state he helped create would soon be embarking on a course that would leave him unfulfilled in subsequent years. Paradise had been sighted after much effort put in by many people but would soon be perceived to be endangered by not a few of those who had fought for the country’s liberation!

Reading the first part of Untranquil Recollections: The Years of Fulfilment (URYF), one is reminded that its author had played a noteworthy part in the making of Bangladesh. He was a key figure in coming up with the economic reasons why Bangladeshis needed to wrest itself loose from Pakistan and stop thinking of themselves as people servicing (West) Pakistanis forever. Striving to create an independent country under Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s leadership had been immensely fulfilling to him and people of his generation; the moment of liberation therefore was truly enthralling.

Given Sobhan’s family history, educational background and the career choices available to him after he had graduated from Cambridge, that he had chosen to play a part in the creation of Bangladesh, or that he had even opted to be in East Pakistan in the first place are amazing facts. Both sides of his family belonged to the landed aristocracy of West Bengal; only his mother’s side had ties to the part that would be East Pakistan afterwards as someone maternally linked to the Dhaka Nawab family. His father was from Murshidabad and would work for the Imperial Police Service of India in postings that had kept him in West Bengal. Sobhan had indeed “travelled a long way” from his “ancestral inheritance” in opting to come to Dhaka for the first time in January 1957 as a 21-year-old man!

As he puts it in the Preface to URYF, Sobhan “chose, deliberately,” to make Dhaka his “home”. He would stay there from then on except on occasions when further studies, or work, or missions on behalf of Bangladesh would take him overseas. His early years had been spent in Kolkata; he studied later in St. Paul’s School, Darjeeling, Aitchison College, Lahore, and Cambridge University. For a while he was in London getting to know the leather business since his father had invested in a tannery in Dhaka after Partition. His settling down in Dhaka was in the main, an “ideological decision” of the young man, as was his resolve to proclaim his “Bangali” identity afterwards. He would subsequently opt to teach at the University of Dhaka and become closely involved in the movement that would give birth to Bangladesh, albeit as “a behind-the-scenes player”.

The shift to academia for this scion of an aristocratic family had a lot to do with the switch from a business career to the years spent in Cambridge. But it was not Trinity Hall, “the small, boutique college” he was admitted to that transformed him to left-leaning views, but Oxbridge’s intellectual ferment of the 50s and the example of someone like Jawaharlal Nehru. The Indian leader’s “life story…resonated with me for its narrative on how a person” from an “elite background evolved into a committed political activist, motivated by a mission to transform Indian society”. Teachers like Noel Annan and Joan Robinson, and “dialectical exchanges” with the likes of Amartya Sen and Jagdish Bhagwati also altered the young man’s mindset, as did intellectual forums like the Cambridge Majlis and the Cambridge Union. The young Sobhan did enter the university town as “a largely apolitical person inclined to view the world from the lenses of the Western educated elite.” But reading “literature from the left,” and the forums he had become a part of, taught him “to assume a more left-nationalist anti-colonial perspective” that encouraged him to veer away from his inherited values. So did his marriage to Salma Sobhan, Hossein Shahid Suhrawardy’s grandchild, Pakistan’s first woman barrister and someone who would set up Ain O Salish Kendra (ASK) and distinguish herself as a woman dedicated to safeguarding human rights. In other words, Sobhan had been veering towards political activism and the rights of people of his “chosen” part of the world through all kinds of choices he made in the 1950s and 1960s.

The University of Dhaka always gets a lot of flak from some commentators as a political hotbed, but Sobhan’s memoir is one more testimony to how its faculty members (as well as students) can be drawn into political movements simply by being present in a place that is at the heart not only of the city but also of the country. Inevitably, then with his left-leaning impulses, and a conscience stirred by regional inequalities he had sighted as an economist, in addition to his travels and education overseas, he got sucked into the political vortex that was the university in the mid-1960s. With like-minded colleagues, he now “engaged in the debate that inevitably focused on the issue of deprivation of the Bangalis”. Critiquing establishment teachers, the Ayub regime and its Bangali lackeys, and coming up with the thesis of “two economies”, Sobhan would soon become part of the think tank that would be advising Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman at this stage of our founding father’s career. As Sobhan puts it, “I was no longer engaged in the study of political economy but had evolved into a political economist.” As such, he was one of the group of economists who would be firming up, first their leader’s six points program for autonomy from Pakistani totalitarian and exploitative rule with facts and figures, and then the election manifesto of 1970 that became part of Bangabandhu’s and Awami League’s march towards a landslide electoral victory in 1970.

But the Pakistani military regime had no intention of giving up power despite the clear mandate on this issue given by the people of Bangladesh to the Awami League. Sobhan now became an even more active participant in the movement for Bangladesh. The climactic part of URYF begins in Chapter 14 and is titled: “Fulfilment: Witness to the Birth of a Nation.” Although seemingly endless obstacles would have to be overcome, including the Pakistani military machine and an unsympathetic American regime, and although the Pakistani leaders would ignore Awami League’s electoral victory and Bangabandhu’s popularity, and cast him into prison and launch a pogrom against Bangladeshi men and women on March 25, 1971, Bangladeshis within the year would claim victory on December 16 with the help of the Indian Army.

After that momentous March night, when the Pakistani army used the most brutal of tactics in a bid to stop the movement led by Bangabandhu to free Bangladeshis from subjection and deprivation, and took him to a prison in Pakistan to silence him and sever him from his people, close aides and advisers of Bangabandhu like Professor Sobhan were especially vulnerable to the blood-thirsty Pakistani army. They then went into hiding or crossed the border not merely to protect themselves but also to contribute to the resistance. Professor Sobhan now switched roles from being a “political economist” to becoming a “political combatant”. The closing pages of URYF reveal the many ways in which he and other Bangladeshi intellectuals close to Bangabandhu worked in their own ways to liberate Bangladesh. He, for his part, crossed the border to Agartala, went to Delhi, then to UK and USA, to meet leaders in the country, work with expatriate Bangladeshis, take the path of diplomacy whenever possible, or do what he could for fund-raising for the Bangladeshi cause and to thwart the Pakistanis. Sobhan even felt heady at that time, discovering the urge to “climb mountains” and even relishing the “multidimensional role” he had assumed as “media star, journalist, diplomat and academic and political rabble-rouser.” No wonder then that at a New Year’s Eve party he and his friends would celebrate the country whose birth they had been witness to, and did what they could for embracing “each other in a spirit of hope and unity”. This was the climax of the “years of fulfilment”; how would they know then that “untranquil years” would follow?

Professor Rehman Sobhan’s Untranquil Recollections: The Years of Fulfilment can be said by way of conclusion is a very readable book introducing us to someone who is very personable and relishes life. His sense of humour and warm personality are among the features of the narrative that endear us to the narrator. So does his modesty and capacity to relish life and good company and embrace the right kind of causes. This, for sure, is a book worth reading and pondering over.

Fakrul Alam is Bangabandhu Chair Professor, Department of History, University of Dhaka.