Published in The Daily Star on Saturday 16 May 2020

Bangladesh has attained considerable development progress in the past three decades. This has led it to enter a dual-graduation phase—moving out from low-income country to lower middle-income country group (World Bank classification) in 2015, and meeting all three criteria for exiting from the least developed country (LDC) group (United Nations classification) in 2018. Bangladesh willingly embraced its graduation journey as it added landmarks to its development milestones. However, the Covid-19 pandemic is amplifying the country’s pre-existing vulnerabilities, and adding new challenges to the progress of the economy and society.

Bangladesh has attained considerable development progress in the past three decades. This has led it to enter a dual-graduation phase—moving out from low-income country to lower middle-income country group (World Bank classification) in 2015, and meeting all three criteria for exiting from the least developed country (LDC) group (United Nations classification) in 2018. Bangladesh willingly embraced its graduation journey as it added landmarks to its development milestones. However, the Covid-19 pandemic is amplifying the country’s pre-existing vulnerabilities, and adding new challenges to the progress of the economy and society.

Covid-19 has been unfolding in Bangladesh at an alarming rate. As of May 15, 2020, 20,065 infections and 298 deaths have been reported, which are the highest numbers among all 47 LDCs. As the country struggles to address the so-called dilemma between saving lives and securing livelihoods, it is obvious that the economy in the coming years will go into a slump, manifesting in loss of jobs, income and savings. These adverse impacts of the pandemic will fall disproportionately on the traditionally “left behind” citizens, slowing down attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Thus, there are justified concerns whether the pandemic will jeopardise the smooth and sustainable transition of the largest LDC in the world. Should Bangladesh defer its LDC graduation, scheduled in 2024? The urgency of a response to this question is dictated by the upcoming triennial review of the United Nations Committee for Development Policy (UN-CDP), where Bangladesh’s progress towards graduation will come up for scrutiny for the second time.

As is known, in order to graduate from the group, LDCs have to meet at least two of the following three criteria for two consecutive triennial reviews: gross national income (GNI) per capita; human asset index (HAI), consisting of education and health indicators; and economic and environmental vulnerability index (EVI) based on a host of structural factors. Alternatively, a country can also graduate upon meeting the “income only” criteria by recording GNI per capita of USD 2,460. Bangladesh is likely to experience deterioration of all the indicators underwriting the three sets of graduation criteria in the coming years.

The GNI per capita of Bangladesh during the last review in 2018 was USD 1,274 (against the threshold of USD 1,230), which may be expected to stagnate, if not fall. Besides an upward estimation of the national income by 15 percent in 2015, three other factors which contributed towards attainment of the income threshold by Bangladesh were robust growth rate of gross domestic product (GDP), high inflow of remittances and stability of exchange rate. International financial institutions have already downgraded the forecast for GDP growth rate between 2-3 percent for the year 2019-20, and more pessimistically for the upcoming fiscal year. Remittance inflows (providing the differential growth between GNI and GDP) are already significantly down, and do not portend well because of the dampened oil price and return of our migrant workers. Due to the emerging weakness in the current account, not the least because of subsidence of apparel exports, the international exchange rate of the national currency may depreciate. All these three factors will be under pressure, and may report a downward trend in the coming years.

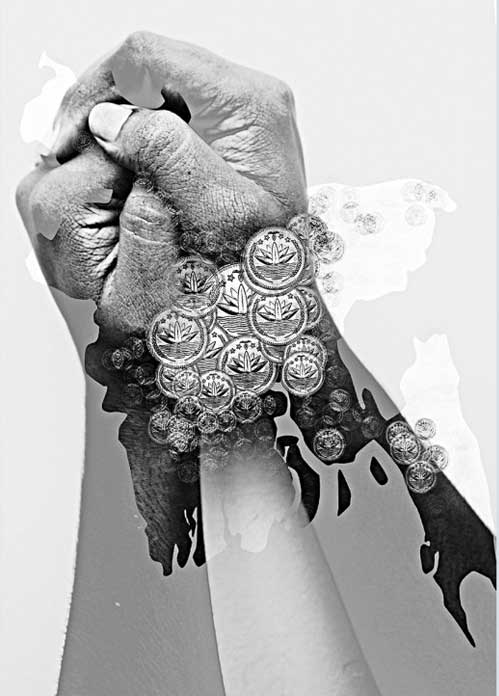

Regrettably, many of the six indicators of the human asset index of Bangladesh, three each from health and education components, will also decline due to the pandemic. The distress in our health sector has been chronic, with budget allocation for health being as low as less than one per cent of GDP. Although maternal mortality and under-five mortality due to Covid-19 infections have been low, these indicators are expected to suffer in the coming months. Increased domestic violence against women are being reported. Pregnant women are opting for unattended deliveries and unsafe practices due to fear of being infected in hospitals. In addition, there is constrained access to antenatal and postnatal services, leading to severe consequences on women’s health. Children under-five and newborns may be deprived of access to nutrition and emergency healthcare during the pandemic, which can lead to malnutrition and make them prone to stunted growth, infections and lethal illnesses.

In the education sector, gross secondary enrollment may fall as the poverty level increases, particularly in the rural areas, in the aftermath of the pandemic. Arguably, the gender parity index for gross enrollment at the secondary level will be most adversely affected as poverty escalates. Grassroots-level information indicates the possibility of higher dropout of female students as incidence of early marriages is on the rise.

Two of the eight Economic and Environmental Vulnerability Index indicators, namely, instability of exports of goods and services and instability of agricultural production, could become important for Bangladesh in the post- pandemic phase. Slackened demand in the global market for both manufactures and services originating from the LDCs is going to affect Bangladesh’s export and remittance earnings. More importantly, if the global economy enters into a protracted recession, prospects for these two sectors will remain unstable, if not uncertain, in the near future.

Regarding agricultural production, it is to be seen how the current aus and the upcoming aman harvests fare in the country.

Paradoxically, during the review in February 2021, the impact of Covid-19 will not be reflected in the available data for the assessment of graduation criteria of the LDCs. However, the UN-CDP has recently adopted a broader assessment framework as well as country-specific risk analysis, to make an informed decision. The candidate countries are entitled to put up their views in written form, and CDP may also seek their advice regarding the graduation process. It will be a country by country decision, including the one on Bangladesh.

At the same time, a growing global sympathy for the LDCs is observed in view of the Covid-19 impact. The G20 has called for special support measures for these countries to help them counter the impact of the pandemic. If this trend gathers momentum, a systemic decision through a resolution at the United Nations may be taken to defer the graduation of all LDCs.

Nevertheless, Bangladesh will have to prepare its technical analysis soon. By staying in the group, Bangladesh may not only continue to enjoy the available preferences, but could also tap into new opportunities. On the other hand, by sticking to the graduation process, the country may use the Covid-induced situation as an opportunity to accelerate its preparation for graduation.

In the final analysis, deferring the graduation of Bangladesh from the LDC group will be a political decision to be taken by the government of the day. In part, it will be dictated by our emotions linked to the 50th anniversary celebrations of the country in 2021. It will also be associated with the development narrative we want to project—a victim of vagaries of nature or a resilient nation in the face of extreme adversities (or maybe both!). Regardless of the choice, Bangladesh will have to take a decision in this regard soon.

Debapriya Bhattacharya and Fareha Raida Islam are Distinguished Fellow and Programme Associate-Research at the Centre for Policy Dialogue, respectively.