Download CPD’s Presentation | See UNCTAD’s LDCs Report 2019

According to the 2018 review of the list of the least developed countries (LDCs), Bangladesh (along with Myanmar) is on of the first historical cases of pre-qualification for graduation through heightened performance under all three graduation criteria (per capita income, human assets and economic vulnerability). Bangladesh is expected to graduate from the LDC group in 2024.

Structural transformation and financing for development

- As of 2019, seven LDCs, including Bangladesh, are meeting the 7 per cent growth target, while the number of LDCs experiencing a contraction of real GDP per capita is only marginally lower than what was peak in 2015–2016.

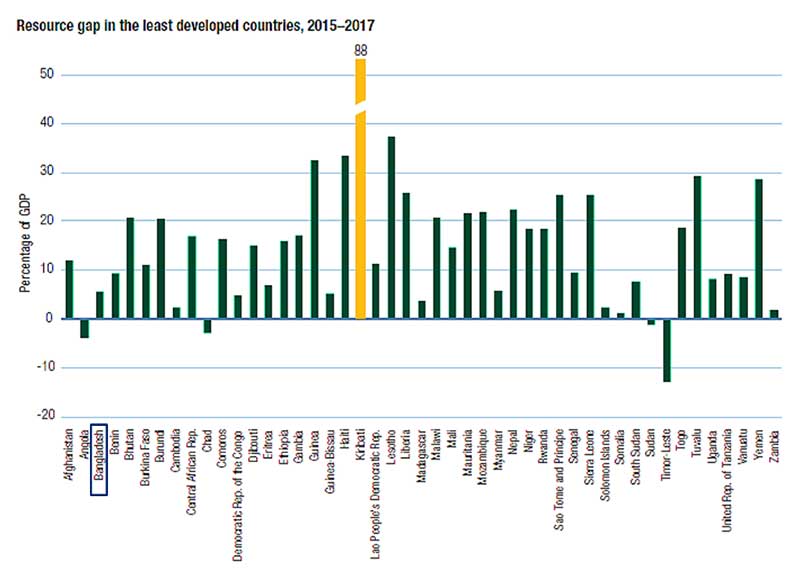

- Resource gap (defined as the difference between domestic savings and gross fixed capital formation) in Bangladesh in 2015-2017 was lower than the LDC average 8 per cent of GDP.

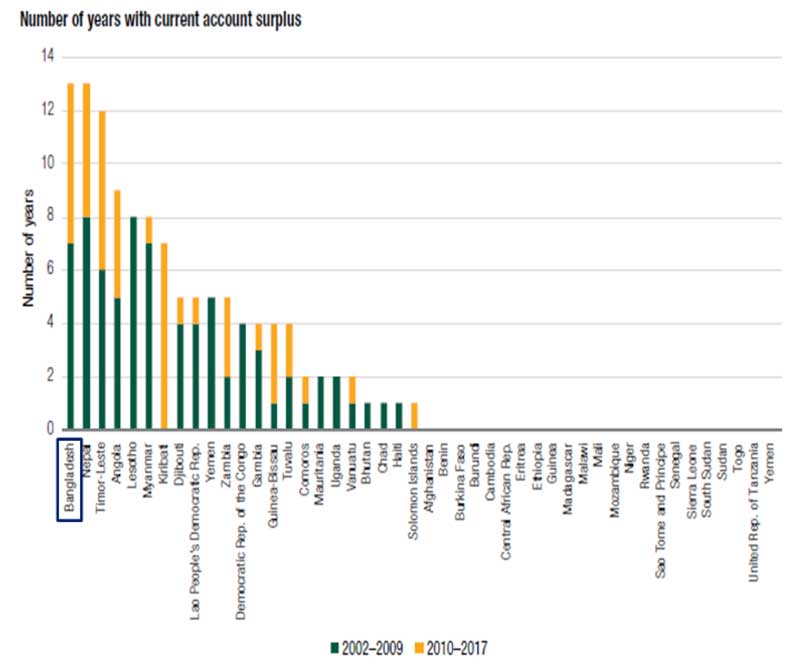

- Bangladesh experienced current account surplus for 13 years during 2002-2017 period. This is largely contributed by remittances from a significant number of workers abroad.

The evolving terms of aid dependence

- The aid dependence (ratio between net ODA in total financing of central government expenditure) of Bangladesh had a ratio lower than 20 per cent.

- During 2015-2017, Bangladesh, Angola, Senegal, Liberia, Cambodia and Afghanistan, in decreasing order of importance, accounted for two-thirds of all other official flows (than ODA) disbursed to LDCs.

- During 2015-2017, the ODA flows have continued to be distributed more evenly across individual LDCs than other official flows or other sources of external finance, such as FDI and remittances. Bangladesh had a very high value (USD 3,691 million) during 2015-2017 in terms of distribution of gross disbursements of ODA.

- During 2015-2017, for Bangladesh, the share of gross ODA disbursements was highest in energy and transport and storage sectors, according to the weight of Aid for Trade subcomponent.

- Bangladesh had the highest share of loans in total ODA gross disbursements which was about 65 per cent in 2015-2017, from around 45 per cent in 2010-2012.

Private development cooperation: More bang for the buck?

Private development cooperation: More bang for the buck?

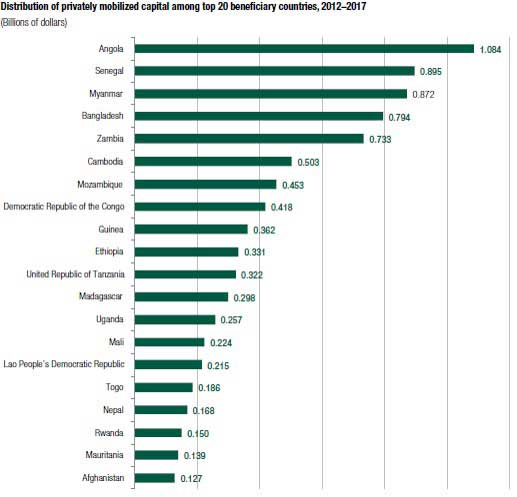

- Bangladesh ranks 4th among the top 20 beneficiary LDCs in terms of distribution of privately mobilised capital during 2012–2017, which accumulated to USD 0.794 billion.

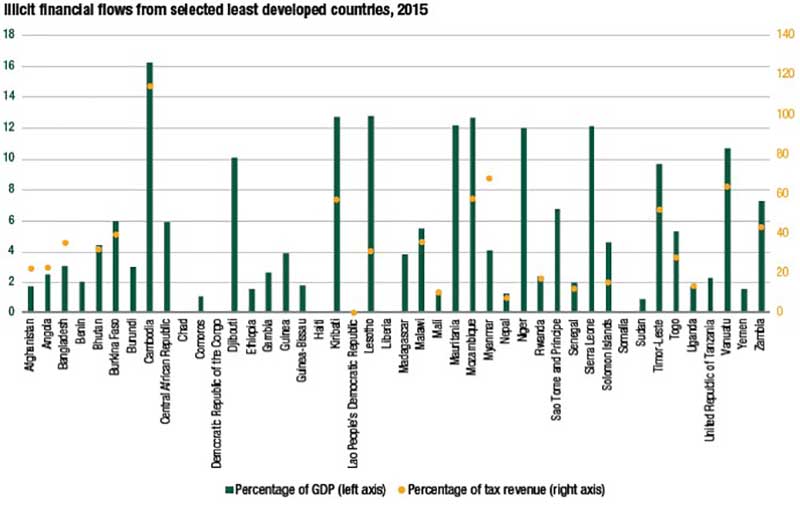

- Cross-border tax evasion and avoidance, linked to the flow of exports and imports, remains a challenge for Asian LDCs like Bangladesh. Potential trade misinvoicing and outflows for Bangladesh, as percentage of total trade with advanced economies, has been estimated to be more than 7 per cent.

External development finance and fiscal space

- Bangladesh remains in the list of LDCs which have less than 10 per cent tax revenue-to-GDP ratio. The analysis of tax revenue potential shows the tax efforts in some LDCs like Bangladesh needs to be improved.

- Bangladesh is among the seven LDCs having relatively lower tax efforts with a score of 0.68, ranking 27th among 29 LDCs.

- Illicit financial flow from Bangladesh, as of 2015, was 36 per cent of tax revenue, which is equal to the average for all LDCs.

- Bangladesh has been listed among the LDCs which are facing an alarming increase both in domestic and external public debt for the last five years.

Policy options

- It will be necessary to revitalise the aid effectiveness agenda established by the Paris Declaration of 2005 on the quality of aid and its impact on development to take into account a significantly changed aid and development finance landscape.

https://www.facebook.com/cpd.org.bd/videos/479973699276749/

- LDC Governments on their parts must assume the driver’s seat of their development agenda and take a more proactive role in managing the allocation of external development finance in alignment with national development priorities. On the other hand, the international community needs to step up their related support towards this common goal.

- Domestic coordination of all external development finance will be critical. This can be done through clarifying decision making process, adoption of mechanisms for efficient disbursement and safeguarding fiscal space, alignment of external support with national development plans, and enforcement of mutual accountability, transparency and monitoring.

- Strengthening the state capacity to drive structural transformation and sustainable development is the key to effectively mobilise and manage domestic resources.

- Actions by the international community in support of LDCs will be a must to delivering the SDG commitments.