Published in Dhaka Tribune on Monday, 20 August 2018

Through their movement, they have opened the gates to improvement

Over the course of a week, our children resurrected hope and restored faith in our hearts that the future of Bangladesh may be in safe hands. In an age where their elders have become jaded and cynical about our state of governance, they have refused to accept the traditional role of passive victims looking to the adult world to resolves their problems.

Over the course of a week, our children resurrected hope and restored faith in our hearts that the future of Bangladesh may be in safe hands. In an age where their elders have become jaded and cynical about our state of governance, they have refused to accept the traditional role of passive victims looking to the adult world to resolves their problems.

They have demonstrated initiative and courage in coming out on the streets, not just to spell out their long-standing concerns over road safety, but to show by example what we need to do about it.

What is troubling to all is the ultimate response to their challenge which has ended in blood and tears instead of inspiring us to follow their lead in reconstructing our approach to governance.

At the outset, we all noted the sober and sympathetic response of the government and particularly the prime minister. We believed that this signalled that the children had indeed brought forth the better angels within us and that we could attempt to draw upon their message to address other areas of deficient governance.

In order to register meaningful appreciation for their efforts, a much broader community of adults, including senior figures from the government, from political parties and civil society, should have symbolically joined the children on the streets and shared in their attempt to enforce road safety rules which have for so many years been ignored.

This would have encouraged them to recognize that their efforts had not been in vain and that they could now return to their classrooms, secure in the knowledge that all the responsible and relevant elements of the adult world could be relied upon to deliver on their message.

The spectre of weaponized goons, in the open presence of law enforcement agencies coming out in full force to drive the students from the streets through resorting to violence will have hardly sent them home with any sense of vindication or confidence that a new order may yet be ready to descend on us.

I cannot speculate on how these young people will react in the future to acts of malgovernance which remain endemic in our society or on what messages they have taken back to their proud but now deeply troubled parents.

The children’s revolution has fortunately not been without some benefit. Legislation for ensuring improved traffic safety has been tabled, with quite positive features. But this legislation has been on the table for at least seven years.

It has now been dusted up with some numerical changes on the years of punishment and the value of the fines. This legislation followed an earlier round of widely publicized deaths from negligent driving which ended the lives of one of Bangladesh’s leading cinema directors Tareque Masud, and eminent journalist Mishuk Munier.

In the wake of that horrific and tragic incident, there was a similar nationwide outcry for action, which perhaps precipitated the original legislation. But at the end of the day, in the face of resistance from the powerful bus owners and workers federations, led by powerful cabinet ministers, the legislation was kept locked in the closet.

Our children have, through their movement, unlocked this closet and hopefully the bill will be shortly voted into law. For this, our prime minister should be rightly complimented and would have earned the approbation, not just of the country but particularly its children.

Whatever may be the limitations of the prospective legislation its enactment will be a positive sum gain. However, as with all our laws, its value will be established less from its proclamation and more through its implementation on the ground.

As we have learned over the years from experience, too much time is invested in writing and rewriting our laws without trying to fully understand why such laws were needed in the first place and why most laws, however adequate or inadequate, rarely tend to be enforced.

Remarkably, our children appeared at this tender age to have gained some profound insights into our country’s incapacity to effectively implement the laws of the land, an insight which appears to have escaped most of their seniors.

The children inspired all of us by highlighting the key message of their revolution “we want justice” and the supporting message “sorry for the inconvenience or delays, state is under repair.”

The children perceptively reminded us that the problems ran much deeper than the incompetence and irresponsibility of a few untrained drivers and originated in our systems of governance.

The children established before our eyes that the system of supervision and accountability within our machinery of governance was malfunctioning on a large scale. Drivers could drive around without papers; where papers were available their provenance was questionable since they may have been obtained without proper tests for the driver and had probably been accessed through payment of money.

Similarly we never know which vehicle is actually unfit to be on the road but carries valid papers to establish its road-worthiness. The interceptions of traffic by the children also pointed to the number of official vehicles which lacked valid papers indicating that a certain category of people remained above the law and need never be subject to inspection.

Our children publicly reaffirmed the now universally recognized truth that we live in a society where one law does not apply to all, a principle which, through the ages, provided the bedrock of a society built on the rule of law.

In Bangladesh, we have all come to recognize that the law is applied, whether for traffic regulation, enforcement of building codes, or debt recovery, quite erratically and inequitably.

This awareness that our enforcement of justice is one-eyed has been absorbed by every law enforcers from their first day on the job. As a result, when conspicuous violations of the law are taking place with impunity we may deduce that the law-breaker is a politically privileged or protected person.

The recent excitement over the identity of perpetrators of violence on helpless student demonstrators by helmet-wearing, stick-wielding young men, has contributed to some peculiar responses from public figures who should, from their own life experience, know better.

Within my political memory, which goes back at least half a century to the era of the Ayub dictatorship in Pakistan, we have been able to readily establish the identity of wrongdoers whether engaged in acts of criminal violence or civil malfeasance.

If the law enforcers conspicuously avoid taking action, we can safely assume that the wrongdoer is associated with the ruling party. Incumbent members of the cabinet Rashed Khan Menon, Motia Chowdhury, Tofail Ahmed, Nurul Islam Nahid, Hasanul Haq Inu were all student leaders or activists during the Ayub era when the hoodlums of the state patronized National Student’s Federation (NSF) ruled the campuses of the then East Pakistan.

These once heroic warriors of yesteryear in the struggle for democracy and self-rule were themselves victims of violence, often by the NSF with abetment of the law enforcement agencies. They knew from experience that however conspicuous were acts of violence by the NSF no action would be taken against them by the state.

Subsequent generations of student activists engaged in challenging the state-patronized hoodlums of the Ershad and the BNP era have learnt from experience that most acts of unchallenged violence by students associated with the ruling party will only be possible if the police stand behind them.

These ruffians, however menacing they may appear, need the law enforcement agencies to protect them if they face any threat of retaliation. They similarly depend on the agencies to provide immunity from any law enforcement, even when such assaults have been transacted in broad daylight and in the presence of the print and electronic media.

In such circumstances, validated by the experience of those in power who were once at the wrong end of a hoodlums’ dao or policemen’s lathi, any time we see on camera or on our TV channels any citizen being assaulted or molested, we can instantly deduce the identity of the criminal by whether law enforcers intervene or stand by as spectators to a publicly committed crime.

The intentions, good or bad of a government towards such open criminal acts is established by whether the wrongdoers are eventually detained by the law enforcement agencies and are then exposed to the full weight of the law.

The confusion over the identities as to who were involved in escalating our recent peaceful protests into violent confrontations should have easily been cleared up. Whenever we witnessed on our TV screens, weapon-wielding goons marching the streets in the company of a uniformed law enforcer and then engaging themselves in attacking other students, their proximity to the state was made self-evident, whether they wore masks, helmets, or even suits of armour.

In the latest phase of public action, a large number of university students are now being detained for interrogation under remand. Unfortunately, not a single perpetrator of violent acts by civilian ruffians captured on camera who were moving side by side with law enforcers to attack the students has been detained.

Similar images of violence captured on camera of public assaults on quota reformers by state-linked students in the presence of law enforcers remain imprinted in public memory. To only initiate action against students, many of whom were victims of violence, remains profoundly unjust and is seen to be so by them.

To be so perceived by a large segment of the student community who are not just voters but also our next generation indicates severe political myopia.

The final stage of an event which should have projected itself as a moment of triumph for collaboration between state and civil society as manifested by our students is, tragically, taking the country on a more uncertain journey.

In moments of civil unrest a variety of players come out to play. Opposition parties, from time immemorial, have attempted to derive political gain from associating with a popular movement. The critical issue, however, remains whether such political forces are the prime movers or even have the capacity to take over a movement and direct it in an anti-government direction.

I cannot think of too many occasions where a strong social movement has been captured and used by a weak political party with even weaker organizational skills. A movement by school-children, followed up by private university students, had a unique authenticity about it because these are non-traditional players who have no record of political engagement or connections.

All that was required of the government was to keep the students’ public presence peaceful and to then let them eventually go home once they had exhausted themselves.

The latest round of oppressive actions against students now appear to relate to the cyber sphere. This is a new world with which I am totally unfamiliar since I neither have a Facebook account nor have a clear idea of how these function.

But what I have learned is that this is the 21st century’s principal medium of communication and far exceeds both the print and electronic media in its reach. In this cyber world every deed and word of a government is open to public scrutiny.

In such circumstances a government should recognize that not all its citizens or the users of the internet are their friends or enemies but may periodically express themselves on particular actions favourably or unfavourably. A much larger number of net users do not create news but merely share it with their friends.

Nor are private citizens immune from such cyber assaults, but can be freely slandered by unknown parties for particular positions they have taken for or against a government or public issue.

A regime needs to recognize that a number of its critics have a long history of commenting on public and private actions of successive regimes and would like to share these opinions with as wide an audience as possible. But such critics need not be enemies of a regime to express themselves unfavourably on particular actions.

I believe and I suspect much of the world believes that the globally recognized photographer Shahidul Alam falls into that category. His camera has, over many years, captured a great variety of events and social struggles with an authority which has earned him both global fame and respect.

All these who fall into the category of conscious citizens and are neither blind nor illiterate about Shahid’s work would know that he falls within the liberal democratic, secular, progressive school of thought, passionately committed both in life and through his work, to the ideals of Bangladesh’s Liberation War.

Throughout his professional career he has been making beautiful, haunting pictures and circulating these around the world to express his own values and perspective on society. I have envied his capacity to tell a story with a single picture.

If Shahid should capture on camera public events which move him but do not show certain public actions in a particularly flattering light or chooses to express himself on the international media as to his opinion of a government, it is his right to do so and does not make him an enemy of the government or a traitor to the state.

All of us have, in our time, been branded as deshodrohi by various regimes and have had the good fortune to discover that our reputations emerged intact but not so that of the regime, whose effrontery in so branding us was widely criticized.

As a person who has throughout his political life been a sympathizer of the political traditions of the present ruling party, I can only feel saddened at this departure from the guiding principles of political action bequeathed to them by our founding father Bangabandhu. Throughout most of his public life, Bangabandhu engaged in politics from the side of the opposition.

He spent many years on the streets resisting oppression, arbitrary detention, violation of human and democratic rights, and spent time in jail, mainly on trumped up charges without any legal merit. Drawing on his political struggles against undemocratic Pakistan regimes, he visualized a Bangladesh where such injustices would never serve as instruments of governance or suppression of the opinions of its citizens.

I am too old now to bring about radical change in my political alignments. All I can hope for, particularly in this sacred mouth of August, dedicated to the memory of Bangabandhu, is that there is still time for course correction by his political heirs to return to the path of engagement with the people, earning their love and support by example rather than demonstrations of muscle power.

As a first step, the government should take the high road and declare amnesty for all the detained university students who have been gratuitously arrested for engaging in peaceful protest and then being attacked for their presumptions.

The granting of bail to some of the students is a positive step forward, and should be extended to all the students, including the quota reform detainees. The administration would also be well advised to grant bail if not release Shahidul Alam from jail. His detention has become quite counterproductive and damaging to the domestic and global image of the government.

Under our constitution, criticizing a government or its actions is not a crime and to now arrest not just someone as eminent as Shahid but other lesser-known people crosses a red line, which drives us towards a darker terrain where not only actions but thoughts must be controlled. Such a system was never part of the legacy of democratic struggle bequeathed to us by Bangabandhu and consecrated with the blood of many political activists.

As a next step, the regime should move to mend its fences not just with an incensed student community but with a broader constituency of sympathizers who remain committed to the spirit of the Liberation War, but now find themselves alienated by the behavior of those on the streets whose violent acts repudiate everything that we fought for.

Some ancient sage once bequeathed a few wise political maxims to guide aspirant political leaders which may be helpful in our confrontational times:

Learn to distinguish your true friends from your true enemies

Try to convert your enemies into your friends

Make sure that your friends do not end up as your enemies

I would like to draw upon these wise political messages to move the present regime to reverse direction from what could be an increasingly unwise course, not just for their future but for the course of democratic politics in Bangladesh.

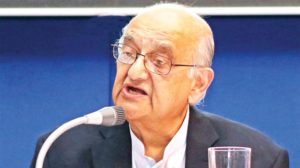

Rehman Sobhan is an economist. He is Founder-Chairman of Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD).