Published in The Daily Star on Friday, 23 March 2018

BANGLADESH’S GRADUATION FROM THE LDC GROUP: PITFALLS AND PROMISES

Why the business-as-usual approach cannot sustain graduation momentum

This is part three of a series of articles based on the Centre for Policy Dialogue’s (CPD) research on Bangladesh’s graduation out of the LDC group. Read the first, second, fourth, fifth and final parts.part.

Dr Khondaker Golam Moazzem and Akashlina Arno

As we know by now, Bangladesh has attained all three criteria for graduation from the least developed country (LDC) group. However, the graduation in 2024 will not be an unmixed blessing for Bangladesh, as the economy is expected to experience a number of challenges in the post-graduation phase. Following graduation, Bangladesh may find it difficult to maintain her global competitiveness and thereby to sustain economic growth unless measures are taken for improvement in structural transformation. (Structural transformation is defined as the transition of an economy from low productivity and labour-intensive economic activities to higher productivity and skill-intensive activities.)

As we know by now, Bangladesh has attained all three criteria for graduation from the least developed country (LDC) group. However, the graduation in 2024 will not be an unmixed blessing for Bangladesh, as the economy is expected to experience a number of challenges in the post-graduation phase. Following graduation, Bangladesh may find it difficult to maintain her global competitiveness and thereby to sustain economic growth unless measures are taken for improvement in structural transformation. (Structural transformation is defined as the transition of an economy from low productivity and labour-intensive economic activities to higher productivity and skill-intensive activities.)

A majority of the LDCs suffer from severe transformation deficits—most of them lack adequate capacity for structural transformation despite the fact that they have experienced considerable economic growth. It is important to examine whether these indicators have adequate influence on structural transformation.

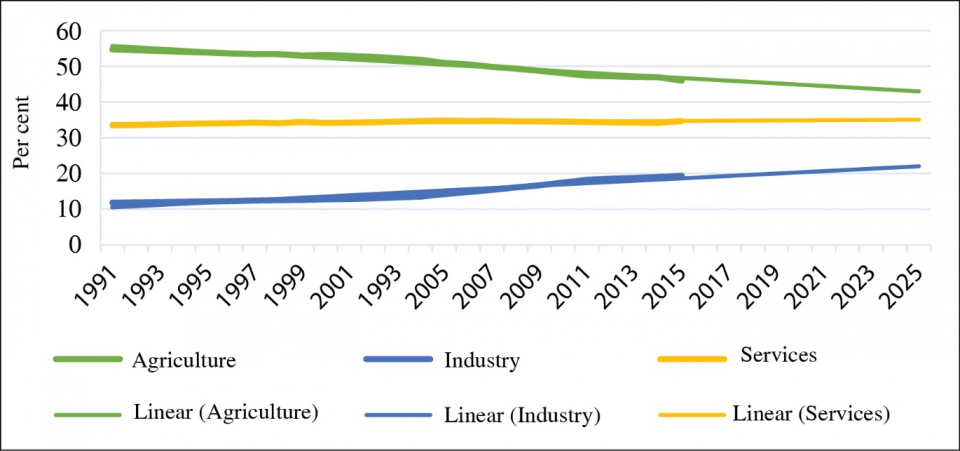

Over the last several decades, Bangladesh has experienced slow progress in structural transformation. The agriculture sector continues to have the largest share of the total labour force despite its low contribution to gross domestic product (GDP), which indicates a low level of structural transformation over the years. The share of the total labour force in agriculture decreased from 51.1 percent in 1995-96 to 43.9 percent in 2015, with a change in the agriculture sector’s contribution to GDP from 21.4 percent in 1995-96 to 15.5 percent in 2015. More importantly, there have been limited changes in sectoral productivity and the movement of labour across sectors, suggesting that structural transformation in Bangladesh is almost stagnant.

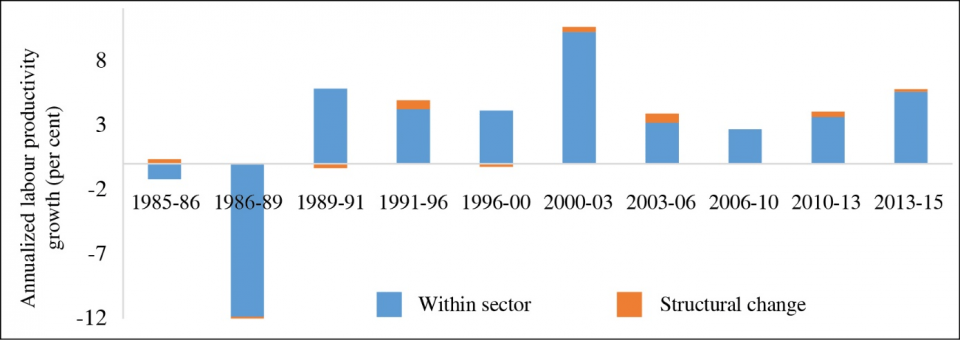

A disaggregated analysis of productivity reveals that the majority of the growth in productivity resulted from the growth of “within sector productivity” rather than “between sector productivity.” “Between sector productivity,” which indicates the structural transformation of an economy, actually decreased from 0.3 percent during 1985-86 to only 0.2 percent during 2013-15, with the average structural change for the 30 years being 0.2 percent.

Export diversification, which is another indicator for structural transformation, has also been found to be weak over the past decades. In comparison to selected export-competing countries such as India, Indonesia, Pakistan and Vietnam, Bangladesh performed the worst in export diversification with a steady rise of the value from 0.33 in 1995 to 0.40 in 2015.

In contrast, the majority of macroeconomic indicators have been found to be favourable over the past two decades in terms of, for instance, consistent economic growth with a rise in per capita income, reduced debt service payments (in terms of GDP) against long- and medium-term loans, less volatile inflation rate and rise in trade openness. All these improved indicators significantly contributed in accelerating external trade, facilitating participation in global value chains and maintaining a stable macroeconomic environment. Despite the positive changes, the economy is expected to struggle, given the present direction of structural change, as it approaches graduation in 2024.

Graduation-led structural transformation indicates Bangladesh’s pathway towards successful structural transformation, especially as it nears graduation from the LDC group. Bangladesh’s future macroeconomic trends appear to be favourable, as most of the indicators such as GDP growth, inflation, debt sustainability and unemployment seem to be moving in a positive direction.

However, Bangladesh’s projected macroeconomic performance until 2024 will partly depend on global macroeconomic conditions in the coming years. Depressed global economic growth is likely to continue and the rise of protectionist measures by Group of Twenty (G-20) countries may have a negative effect on Bangladesh’s export trade environment. During this period, the share of the total labour force in agriculture is expected to gradually creep downwards, while the share in industry is expected to rise.

An alarming trend, however, is that the movement of labour in the services sector, on which Bangladesh’s economy relies heavily upon, is very slow. Analysis shows that while Bangladesh does not exhibit a decline in “between sector productivity” growth, the pathway to structural transformation in 2025 will not improve. Therefore, even with a relatively high level of productivity, the trends for higher structural change seem to be limited.

Structural transformation-enabled smooth transition after graduation indicates how structural transformation and graduation from the LDC group are connected. As observed in the cases of graduated economies, the transition to graduation is difficult in the absence of structural transformation, especially when economies lose trade preferences and other special and differential treatment provisions. An economy experiencing graduation could maintain a position of strong structural transformation if it fulfills certain conditions. Analysis shows that a) the economies starting with a large share of the labour force employed in the agriculture sector have a higher potential for structural change and b) macroeconomic stability in terms of inflation rate and private investment is significant for structural transformation. In contrast, the graduation criteria have little effect on structural transformation. Given the different levels of importance of the abovementioned issues, the pathway to graduation needs to consider other criteria that directly affect the structural transformation of an economy.

For Bangladesh to overcome the challenge of slow structural change, policies targeting the growth of more productive sectors, such as manufacturing and services, need to be implemented. According to its Seventh Five Year Plan (7FYP), Bangladesh’s government plans to promote structural transformation by developing the manufacturing and services sectors (Planning Commission, 2015). Its strategy for the manufacturing sector is to encourage higher investment and foreign direct investment (FDI) towards export-oriented manufacturing. FDI not only encourages increases in private investment required to increase productivity but also enables the “spillover effect” which happens through transfer of better technology and managerial skills from the economies that provide investment.

To sustain long-term structural change, the services sector has to be modernised in terms of both technology and skills. According to the 7FYP, Bangladesh’s government is expected to concentrate on three industries including international transport, tourism and information and communications technology services. It plans to implement a deregulation plan for private investment in traditionally public industries such as education, information and communications technology services, aviation and electricity. It encourages investment to upgrade education and training quality, including an emphasis on expanding tertiary education. The objective is to significantly increase both labour productivity and sectoral productivity to be prepared to compete in the global market.

Khondaker Golam Moazzem is research director and Akashlina Arno is former research associate at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD).