Published in Dhaka Tribune on Saturday, 26 March 2016

An accidental diplomat’s war of liberation

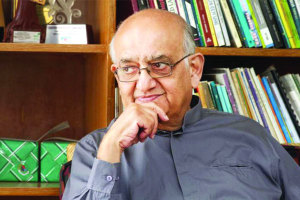

Habibul Haque Khondker

Rehman Sobhan’s memoirs provide a window into the War of Independence

On March 27, 1971, Rehman Sobhan, an economics professor of Dhaka University, with close association with the leadership of the Awami League, busy negotiating with the Pakistani officials about the rightful share of the then East Pakistan as Bangabandhu was negotiating with President Yahya Khan, left home for India.

On March 27, 1971, Rehman Sobhan, an economics professor of Dhaka University, with close association with the leadership of the Awami League, busy negotiating with the Pakistani officials about the rightful share of the then East Pakistan as Bangabandhu was negotiating with President Yahya Khan, left home for India.

On a small boat, his own fate was as uncertain as that of Bangladesh — as he recollected many years later in his autobiography, Untranquil Recollections: The Years of Fulfilment (Sage, 2016). A reviewer of his wonderfully written memoirs, Lincoln Chen, an American professor and a friend of Bangladesh, wondered: Why fulfilment?

The fulfillment for Sobhan was seeing Bangladesh’s liberation, a dream that finally materialised on December 16, 1971, which he saw from his temporary house at Oxford on TV with a broken ligament sustained at the UN building in New York. Though he saw the surrender ceremony on TV, he was fortunate to see the buildup leading to the war of liberation from the ringside.

Until December 15, 1971, Sobhan, an officially anointed “envoy extraordinaire” by the Mujibnagar government, lobbied hard at the United Nations. He moved from lawmakers’ offices in Washington, DC to persuade them to support the cause of Bangladesh.

He was on a personal mission to win the hearts and minds of politicians, intellectuals, and public figures in the West for whom Bangladesh was a remote news bite, far removed from their day to day preoccupations.

Rehman Sobhan’s journey began in 1957 when a 21-year-old Cambridge graduate landed in Dhaka. He called Bangladesh home, even though his facility with the Bangla language was almost non-existent. His power of articulation in English is exceptional. I remember distinctly the day in December 1996 when Rehman Sobhan was recollecting his days of diplomacy at a conference held at Columbia University, New York to celebrate 25 years of Bangladesh. He mentioned the unforgettable Aretha Farnklin’s hit song of 1971, “Spanish Harlem.”

His eloquence charmed the audience so much that a woman seated next to me whispered into my ears: “I wish I had his power of articulation.” The lady in question was Shelly Feldman, a Cornell Professor. Sobhan’s power of articulation on a live television show of PBS in Boston in 1971 impressed a young Benazir Bhutto, then at Radcliff college, a sister institution of Harvard, so much so that after many years as prime minister of Pakistan, she once referred to him as “the Rehman Sobhan.”

Such a gift of gab that Sobhan cultivated in his school days at St Paul’s, Darjeeling, Aitchison College, Lahore, or Cambridge, where he was the president of Majlish, came handy in his role as an envoy for a country yet to be born. It is his boarding school experience of living in the Spartan way that helped him, squatting in his host’s living room in Washington, DC or in Kolkata.

He embarked on a diplomatic role and headed for America in a borrowed, oversized overcoat of a friend in Delhi. Sobhan as an envoy for Bangladesh was on a mission to lobby hard to persuade the Aid consortium for Pakistan, joint meetings of the IMF and World Bank not to give aid to Pakistan unless it stops genocide in Bangladesh.

It was his Cambridge connections that helped him establish linkages to an international, old boy network, some of whom were economists and others prominent journalists.

As an essayist of distinction, Sobhan wrote for The Guardian, New Statesman, The Nation, and several other print media in the West to publicise the cause of Bangladesh. He gave speeches and participated in debates at Cambridge, The Chatham House, Sorbonne, Paris, Yale, MIT, the University of Pennsylvania, Syracuse University, and Williams College to drum up support for Bangladesh.

A scion of high nobility of Murshidabad from his father’s side and the Nawab family of Dhaka from his mother’s side, he was known for his simplicity. His lifestyle was unassuming; the furniture of his modest Gulshan house was Spartan. He dedicated his life to public service.

But it is his elite background that gave him a ringside view of history. He met Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, the president of the All Pakistan Awami League, at the residence of Kamal Hossain, whose father was Suhrawardy’s physician.

He met Bangabandhu along with Chief Minister Ataur Rahman at the residence of his nana, his maternal grandfather, Khwaja Nazimuddin in 1957.

He also met Bangabandhu at the hospital room of Mian Iftikharuddin, president of a small opposition party of Pakistan. But it was not until 1964 that he developed a close relationship with the founder of future Bangladesh.

It was in 1964 when Bangabandhu invited Kamal Hossain and Rehman Sobhan to help draft the manifesto for the 1964 elections. When Ayub Khan declared his candidacy for the 1964 elections and issued a list of his achievements, Bangabandhu asked the duo to contribute to the drafting of his response.

Sobhan fondly recollects Bangabandhu’s greatest quality to reach out to people and draw upon their perceived qualities at the service of the nation.

Rehman Sobhan, along with a group of brilliant Bengali economists at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, developed the germs of the two-economy theory in the early 1960s for which many give Sobhan singular credit. Sobhan shares this glory with his colleagues.

Inclusivity is one of Sobhan’s virtues. It is quite likely that through his sportsmanship — from boxing to hockey, he developed a team spirit. A considerable part of his 444–page memoir is devoted to the stories of his friends from the tennis pitch of South Club, Kolkata, St Paul’s school and Cambridge.

Sobhan is endowed with an amazing memory with names. In a recent interview, I pressed him, whether he kept a diary or Googled the spelling of some of his old friends. He assured me that he remembers the names and places very well.

A truly public intellectual, Sobhan wrote penetrating analyses of economic disparity between the two wings of Pakistan. His book on basic democracy was an expose on Pakistan’s authoritarian rule under the garb of democracy. As a teacher at Dhaka University, he fired the imagination of a future generation of economists, civil servants, and political leaders.

Later as head of BIDS and the founder of the Centre for Policy Dialogue, he was able to mobilise a fine group of economists dedicated to public service.

Rehman Sobhan’s memories take the readers to so many untold stories of the challenges of the liberation war, the intrigue in Kolkata between the Mujibnagar, 8 Theatre Road, and the Bangladesh Foreign Ministry at Park Circus where Mushtaq and his gang were conspiring with the US officials.

His masterly narratives vividly record the story of sacrifice and commitment of so many who cast their lots with the cause of Bangladesh. Americans, Indians, the British, French academics, philosophers, and ordinary men and women who were able to make the right choice, in favour of justice. Some made the right choice on their own, others needed a little persuasion.

The memoirs of Rehman Sobhan, a freedom fighter extraordinaire, ends on the last day of December 1971 when he returns to Dhaka after accomplishing his mission.

His memoirs provide a window into the complicated political and diplomatic processes of the background of the War of Independence and the historical antecedents that led to the birth of a nation. The process, surely, was untranquil.