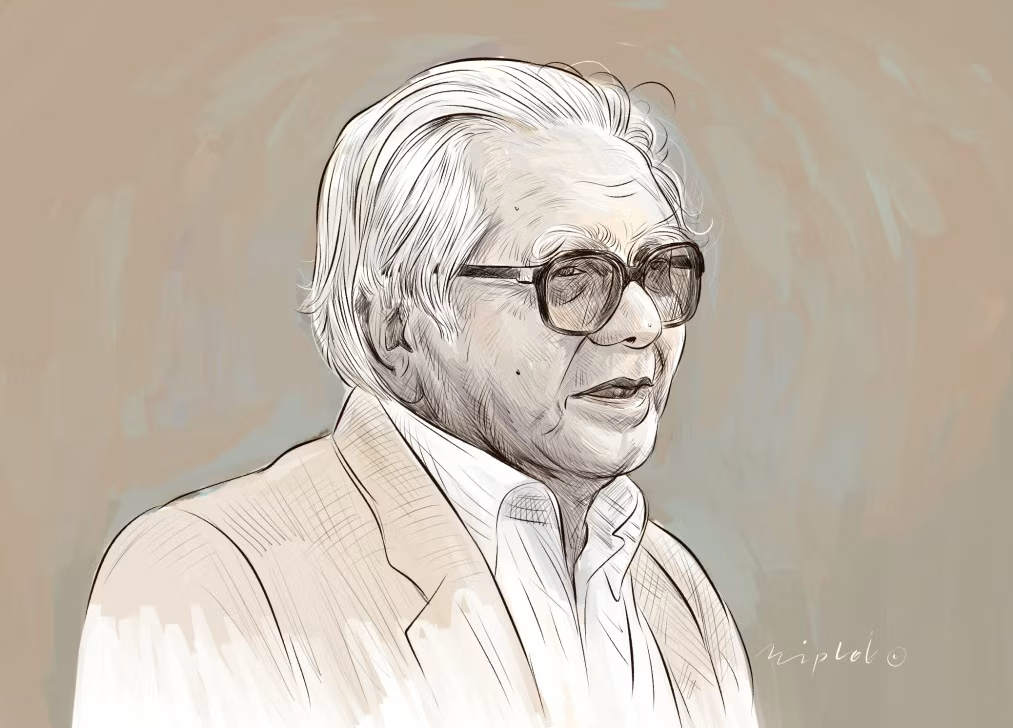

Originally posted in The Daily Star on 13 September 2025

I have just bid farewell to yet another dear friend and comrade with whom I embarked on a journey towards a more just Bangladesh nearly six decades ago. I was introduced to Badruddin Umar by our mutual friend Mosharraf Hossain sometime around 1961. Umar had just returned from Oxford where he had graduated with a degree in PPE (politics, philosophy and economics). Mosharraf, Umar and I believed in a socialist future for what was then East Pakistan, though Umar’s approach to socialism was much more solidly grounded than mine and was firmly anchored in the Stalinist variant of socialism. Umar believed, and possibly continued to believe to the end, that the decline and disintegration of the Soviet Union began with the death and repudiation of the Stalinist legacy by his successor Nikita Khrushchev.

The finer points of socialism and the nature of a socialist society remained an ongoing discourse with Umar over the next 62 years. We had fierce debates on politics and policy, which were intensified once I became involved in the political movement for self-rule for Bangladesh. In the post-liberation period, during my tenure as a member of the first Planning Commission, along with Mosharraf Hossain, Anisur Rahman and Nurul Islam, Umar in the columns of the Holiday was a regular, if not always well-informed, critic of our policies. Yet, over the years of intellectual and political contestation, Umar remained one of Mosharraf Hossain’s closest friends and a good friend to me. We argued and disagreed, but the relations remained civilised and never crossed the bounds of decency.

Umar was more than a friend; he was also a relation through my late wife, Salma Sobhan. Salma’s mother, Shaista Ikramullah, and Meherbano, Umar’s mother, were first cousins. Umar’s grandmother and Salma’s grandfather, Prof Hassan Suhrawardy, were children of the reputed scholar Ubaidullah al Ubaidi, founder and principal of the Aliya Madrasa in Dhaka. Umar was, thus, a legatee of a political aristocracy where his great grandfather Abdul Jabbar Khan, his grandfather Abul Kasem Khan, and his father Abul Hashim were important figures in Bengal politics over the course of a century.

Our family relationship rarely intruded into our personal and professional relationship. In 1961, when Kamal Hossain and I decided to establish a think tank, the National Association for Social and Economic Progress (NASEP), we drew in Mosharraf Hossain, then a reader in economics at Rajshahi University, and his two university colleagues, Prof Salahuddin Ahmed from the history department and Badruddin Umar, then a reader in the political science department. In those days, we identified the primary contradiction within the Pakistan state as the undemocratic nature of the state and its consequential implications for denial of self-rule for the Bangalees. We also believed in the need for a secular, egalitarian, social order with our own varied perspectives on the nature of a socialist system which would be appropriate for our society. NASEP sought to initiate debate to explore policy options for the then East Pakistan. We prepared a number of pamphlets on the challenges of democracy, disparity and education, and on the challenge of communalism, prepared by Umar.

The finer points of socialism and the nature of a socialist society remained an ongoing discourse with Umar over the next 62 years. We had fierce debates on politics and policy, which were intensified once I became involved in the political movement for self-rule for Bangladesh.

Umar, more so than other members of NASEP, had very little confidence in the Awami League, then led by HS Suhrawardy, who was in fact his mamu as he was Salma’s mamu. Umar was highly critical of Suhrawardy as the prime minister of Pakistan when he declined to honour the 21-point manifesto of the Jukto Front, which swept the 1954 provincial elections in East Bengal, demanding that Pakistan withdraw from the US-led military pacts of CENTO and SEATO. Here, all of us at NASEP were in full agreement with Umar. I had, indeed, as a student in Cambridge, participated in a debate between the Cambridge University Majlis and the Cambridge Conservative Society, where I had argued along with Amartya Sen and Arif Iftikhar, “This house rejects SEATO.” When the AL split on this issue of the US alliance and also on the demand for full autonomy for East Pakistan, Umar strongly identified with Maulana Bhashani and the politics of the National Awami Party (NAP) founded by him.

Among all of us at NASEP, Umar was the most politically oriented and believed that it was not enough to just write and debate about politics; we needed to be directly engaged in the process. Somewhere around 1968, Umar made a life-changing decision to join politics, not just as a part-time activist but on a full-time basis. A number of academics and professionals did indeed become members of political parties without leaving their income-earning professions. But few Bangalee Muslims such as Prof Muzaffar Ahmed, who had become one of the leaders of NAP, had opted to actually do so on a full-time basis. In the case of Umar, this meant resigning from his position as professor and chair of the Department of Political Science at Rajshahi University. He was already under attack by the then governor, Monem Khan, for his critical writings against state policy, as were some of us in the economics department at Dhaka University.

Since neither Umar nor his wife owned any income-generating assets, the only source of income available to the family was Umar’s salary from Rajshahi University. His resignation thus had severe implications for the livelihood of his family, which included three children: a son and two daughters.

This absence of a regular source of income for Umar prevailed to the end of his life. Fortunately, his wife Suraiya could be provided with employment in a bank just after liberation, and she remained the principal breadwinner of the family. After her retirement, Suraiya continued working at Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK) for a number of years. Umar’s son Sohel is now well-established as a professional in a company and could help his family.

It would, however, be unjust to say that Umar remained exclusively dependent on his family members for the upkeep of the family. He was a prolific writer, with a large readership across Bangladesh, India and even internationally. I will have more to say about this later. But royalties from his writings provided a significant contribution to the family coffers and continued to do so to the very end of his life. His definitive work on the Language Movement of 1952 is still in print after 60 years and continues to provide him with royalties along with many other of his publications.

Umar’s heroic and principled decision to commit himself to full-time politics unfortunately came at an unpropitious moment. His political engagement was associated with his commitment to join the then Communist Party. The East Pakistan Communist Party (EPCP) had unfortunately gone through a number of divisions in the 1960s, associated with the split in the global communist movement between Moscow and Beijing. A once powerful left movement associated with the NAP and backed by a united underground Communist Party had weakened itself through division. One faction of the EPCP, associated with China, sided with the Maulana Bhashani-led faction of NAP. The other, pro-Moscow faction backed the segment of NAP led by Prof Muzaffar Ahmed.

Towards the end of the 1960s, the pro-China component of the NAP-EPCP alliance further weakened itself by sub-dividing itself into four factions: one led by Maulana Bhashani, which served as the NAP; another faction led by Mohammad Toaha and Abdul Haque, which was joined by Umar; a third faction led by Matin and Alauddin; and a fourth faction led by Abul Bashar, the trade union leader, Kazi Zafar, and Rashed Khan Menon. At that time, the pro-China faction of the left were far from clear about where they stood in relation to the Bangalee nationalist movement, which was reaching its apotheosis through the Six-Point Movement led by Bangabandhu. Umar in his own writings strongly argued for the left fully committing itself to the emerging struggle for a self-ruled Bangladesh, but such a clearly defined position was not decisively embraced by the left factions.

Umar wrote in Volume 2 of The Emergence of Bangladesh:

“Bhashani was invited to China for a visit and he left Dhaka on 29 September 1963 after meeting Ayub Khan in Rawalpindi on the way. They reached some political understanding in the context of Ayub’s changed attitude towards the US and Bhashani’s visit to China was the result of this new-found relationship between him and Ayub Khan and further strengthened the bond between him and the pro-Chinese Communists and led to a softening of his attitude towards Ayub Khan, who was considered as an ‘anti-imperialist’ factor in the region” (Page 83).

Whatever may have been the outcome from Umar’s political activism, as a scholar and intellectual of the left, he remained a powerful figure till the end of his life. As a scholar, I would personally rate Umar as the most outstanding political historian produced by Bangladesh. His historic work on the Language Movement in East Pakistan remains the definitive work on this historic phase of the nationalist struggle.

Umar remained associated with Toaha during the Liberation War, but had disagreements with him on the role of his party in the Liberation War and eventually left the party. For most of the 54 years after the liberation, Umar remained involved with the left movement both at the grassroots and cultural levels. He was associated with a left group led by himself and Prof Shahiduddahar. They once invited me to address one of their discussion groups on agrarian reform, a subject on which I had earlier published a book. I do not have much knowledge of this final phase of Umar’s political life, but it does not appear that his involvement did much to advance the left cause, which remained divided and ineffective.

Whatever may have been the outcome from Umar’s political activism, as a scholar and intellectual of the left, he remained a powerful figure till the end of his life. As a scholar, I would personally rate Umar as the most outstanding political historian produced by Bangladesh. His historic work on the Language Movement in East Pakistan remains the definitive work on this historic phase of the nationalist struggle. The work is clearly informed by a political perspective, but the scholarship, with access to primary sources of information such as the detailed diaries of Tajuddin Ahmad, remains without equal. The volume, based on deep research carried out without any institutional support or financial backing, was a labour of love by Umar and the product of a true scholar. The work is still in print after 60 years and will be read long after Umar’s departure.

Umar has written other works on political history. Of these, one of his most important works is provided through his two-volume publication, The Emergence of Bangladesh (OUP, 2004). This work originated in a series of articles Umar had begun publishing in the Holiday. I read these articles with interest and was deeply impressed by the highly informative and analytical quality of his work, which I believed should be widely read by a generation who had little if any memory of the historical antecedents of the emergence of Bangladesh. I suggested to Umar that he should collect these articles together and publish this as a coherent volume of political history. Umar was unsure if his version of history would find ready publishers in Bangladesh, so I suggested that I could reach out to Oxford University Press (OUP) in Pakistan, which could also provide a large market in Pakistan, since the work covered the entire period of Pakistani rule up to 1971.

I contacted the CEO of OUP in Pakistan, Ameena Saiyid, who was well-known to me. She had transformed OUP in Pakistan into a globally recognised brand, whose books could be found on the shelves of bookshops and libraries not only in Pakistan but also in India and around the world. Ameena readily responded to my suggestion and OUP, after some hiccups between Umar and his editor at OUP, went ahead and published both volumes, which were widely acclaimed. Once OUP surrendered its copyright after exhausting the sales potential of the work in Pakistan, Cambridge University Press in India took up the publication of the two volumes. I have read, learnt much and drawn upon both volumes in writing parts of my memoir. The two volumes are again well-researched and written from a left perspective. Indeed, the first volume is sub-titled Class struggles in East Pakistan, 1947-58. Umar’s political perspective did not prejudice the width and depth of the historical research informing his work in these volumes.

Beyond his political activism and scholarship, Umar was an exceptional human being. He cherished his family, who remained devoted to him to the end. His wife Suraiya was a pillar in his life, where not only did she serve as a breadwinner but also as a pillar of the family where Umar’s long absences in the field and his risk-prone involvement in political movements exposed the family to much insecurity. Both Mosharraf’s wife Inari and Salma were especially close to Suraiya, who treated them as her elder sisters.

For all the tribulations he faced and the intensity and passions underlying his political conflicts, not just with successive regimes but within the left, Umar retained his sense of humour and civility in his social life. In our final encounter at my home in April of this year, he was in top form. He had lost most of his hearing, but not his eloquence and sharpness of mind. He could not attend my 90th birthday celebrations due to illness, but felt obliged to subsequently call on me as an old friend to contribute to the celebrations. His anecdotes were full of humour, where he laughingly observed that the harshest criticisms he received in his life were not from his ruling class enemies, but from the divided community of the left.

Umar is and will be remembered today as a committed and uncompromising icon of the left. He invested his scholarship as well as his public activism behind various struggles of working people, the unending fight against autocracy, the global war against imperialism, and what Umar regarded as the deeply divisive menace of communalism. But in any final analysis of his life, it will be his works of scholarship which will invest him with immortality.

Prof Rehman Sobhan, one of Bangladesh’s most distinguished economists and a celebrated public intellectual, is founder and chairman of the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD).

Views expressed in this article are the author’s own.