Originally posted in The Daily Star on 5 November 2024

Bangladesh’s shared GIs with India: The conflict and the outlook

In the recent past, the topic of shared Geographical Indications (GI) between India and Bangladesh has frequently appeared in public discourse. A comparative review of the GI journals published by the Department of Patents, Designs and Trademarks under Bangladesh’s Ministry of Industries and Intellectual Property India under the Ministry of Commerce and Industry reveals that at least eight products are recognised as GIs in both countries, reflecting historical and cultural overlaps.

In the recent past, the topic of shared Geographical Indications (GI) between India and Bangladesh has frequently appeared in public discourse. A comparative review of the GI journals published by the Department of Patents, Designs and Trademarks under Bangladesh’s Ministry of Industries and Intellectual Property India under the Ministry of Commerce and Industry reveals that at least eight products are recognised as GIs in both countries, reflecting historical and cultural overlaps.

For instance, Bangladesh’s Nakshi Kantha from Jamalpur corresponds to India’s Nakshi Kantha from West Bengal, while Chapainawabganj’s Khirsapat Mango parallels Malda Khirsapati (Himsagar) Mango in India. Similarly, Rajshahi-Chapainawabganj’s Fazli Mango is registered as Malda Fazli Mango in India, and the renowned Dhakai Muslin in Bangladesh is registered as Bengal Muslin in West Bengal. The Jamdani saree, another significant traditional craft, is registered in both Dhaka, Bangladesh, and West Bengal, with further Indian registrations for Uppada and Fulia Jamdani sarees. Gopalganj’s Rasogolla also has its counterpart in India’s Banglar Rasogolla, and Tangail saree of Bangladesh has been registered as Tangail saree of Bengal in West Bengal. This shared registration pattern underscores the need for comprehensive legal protections to avoid conflicts, particularly as both countries seek to capitalise on the economic and cultural values of these products.

Products registered as GIs under both Indian and Bangladeshi jurisdictions due to overlapping geographical areas or historical connections fall under the category of trans-border GIs. A trans-border GI originates from a geographical area that extends over the territories of two adjacent contracting parties. While trans-border GI conflicts are not particularly common, they do occur globally. These conflicts arise when producers from different countries seek GI protection for similar products.

Given the reputation and consumer faith that a GI status brings, it is in the economic interest of every country to register as many GIs as possible for their traditional products, regardless of the ambiguity of the exact geographical linkage. The motive behind seeking such protection is entirely rational from a national interest perspective. Consumers associate GIs with specific qualities and origins, differentiating them from similar products. They help develop collective brands for products with shared geographical characteristics, building a stronger market presence. It can also prevent unauthorised use of the indication by others ensuring only qualified producers benefit from its reputation. Additionally, GIs can lead to competitive advantages, premium prices for higher product value, increased export opportunities, stronger brand image, and higher export prices. The significance of these products extends beyond market economics and increased profits; they often embody the heritage, tradition, and culture of their place of origin.

However, when multiple countries register GI for a product separately under the national jurisdiction or the “Sui Generis System” of World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)—which protects at national level only, it may make the GI product semi-generic, where the name merely becomes a description or class of product that can be produced in several countries. This may undermine the ability to command premium export prices as neither country can establish exclusivity over the product (as seen with Basmati rice) and may even result in a loss of protection against imitation. Furthermore, there remains apprehension about legal disputes in case either country attempts to deter the other from entering international markets.

To illustrate the gravity of the issue regarding the shared resources and their GI registrations between India and Bangladesh, below we briefly analyse two case studies:

Tangail saree is now an Indian GI

The Tangail saree is a longstanding cottage industry in Bangladesh, tracing back to the British era. These are completely made by handwork. Tangail’s zamindars patronised Dhaka Jamdani weavers during the British colonial period. Over time, these weavers innovated various motifs, shaping the Tangail saree as we know it today.

On January 4, 2024, the Tangail saree was officially registered as a GI of India under the title “Tangail saree of Bengal.” Coming to know about the Indian action, the agony and anguish of the people of Bangladesh were expressed through public outrage, including those of the weavers and the local people of Tangail.

Bangladeshi Tangail saree has a global market, spanning Europe, North America, the Middle East, Japan, and several Indian states. Bangladesh exports about 50,000 sarees to India every week. By registering a GI for Tangail saree, India has demonstrated an inclination to “free ride” which may lead to unfair competition for Bangladeshi producers of Tangail saree. Although Bangladesh completed the GI registration for Tangail saree on April 25, 2024, this is not going to stop India from using the GI of Tangail saree and capitalising on it. India now has the opportunity to capitalise on the heritage brand of Bangladeshi Tangail saree, which was built over 250 years.

India claimed the GI based on the argument that “Basak,” the key weaver family of Tangail saree migrated to West Bengal post-partition in 1947 and again after the Liberation War of Bangladesh in 1971. They claim this category of saree to be a hybrid of Shantipur design and Dhaka-Tangail. However, the documentary evidence submitted in the GI Journal of India nowhere had the mention of “Tangail saree of West Bengal,” rather one of their submitted documents referred to Tangail of Bangladesh as the place of origin of Tangail saree. Based on these fuzzy arguments, the Indian GI registration for Tangail saree is neither fully factual nor compelling.

As specified by WIPO, GIs must be linked to products produced in a specific territory. Bangladesh had a strong case to contest this GI as the Indian GI refers to “Tangail saree,” which is a specific geographic location in Bangladesh.

Building on this foundation, in May 2024, Bangladesh decided to legally challenge the “Tangail saree of Bengal” GI by India. A first draft has been prepared to contest and the legal team has continued its effort to gather further evidence to strengthen their case.

Sundarban honey GI conundrum

As the backlash from the controversy over the GI awarded to India for Tangail saree began to simmer down, a new concern emerged. Sundarban honey was displayed as a GI product of India at the Diplomatic Conference on Genetic Resources and Associated Traditional Knowledge organised by WIPO in Geneva (May 13-17, 2024).

This sole representation of the said product by India sparked questions in our minds as the majority of Sundarban’s territory lies within Bangladesh. Indeed, Bangladesh is the primary extractor of Sundarban honey. While official government records could not be found, media reports indicate that about 200-300 tonnes of Sundarban honey are extracted annually, while India produces about 111 tonnes per year as mentioned in its GI application.

Curiously, the district administration of Bagerhat filed an application for the GI tag of Sundarban Honey on August 7, 2017. Yet for seven years there had been no development. This is a rather astonishing example of administrative dereliction of duty. The initiatives to secure GI status for Sundarbans’ honey only gained traction after we drew attention to the matter through a media briefing organised at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD). The GI registration for Sundarban honey was finally completed in Bangladesh in July 2024.

Contrary to Bangladesh, West Bengal Forest Development Corporation Limited of India applied for GI rights for Sundarban Honey on July 12, 2021. The GI tag was vigilantly issued on January 2, 2024. Consequently, India once again surpassed Bangladesh in the GI registration of shared resources. As a result, India alone received global recognition for the genetic uniqueness and traditional collection methods of Sundarban honey, while Bangladesh’s contribution remains overlooked.

Way forward

Given the ongoing disputes surrounding GIs between Bangladesh and India, questions loom over the equitable recognition of trans-border GIs of Bangladesh. One can safely say that these are not the last incidents between Bangladesh and India. Without any established legal framework, tensions may continue to rise regarding trans-border GI protection. Given the contingency of geographical proximity and shared natural resources, Bangladesh should find a mechanism to systematically protect its GIs and look for a predictable legal solution to address the issue of GI conflicts of shared geographical resources. In view of that, we would like to make the following recommendations:

– It is important to have an assessment of the list of Bangladeshi GIs. There is a need to be clear on which Bangladeshi GIs have export potential, especially in Lisbon contracting states. Converting these into global products is essential to fully reap the benefits.

– GIs must be secured for all products with geographic reputation and export potential. The prerequisite for any country to protect its origin-based traditional products is to register them first in the country of origin.

– To seek protection internationally, GIs must be registered separately in each jurisdiction where protection is desired, often through bilateral agreements. The Lisbon Agreement for the Protection of Appellations of Origin and their International Registration (1958) can also be utilised. The Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement on Appellations of Origin and Geographical Indications, adopted on May 20, 2015, revised the pre-existing Lisbon Agreement. Although the number of signatories to this act is still limited to 44 countries, it could be an important first step for extending supranational protection of GIs alongside Appellations of Origin (AOs).

– Registering collective marks for the country’s GIs should also be given thought. The primary purpose of collective marks is to indicate the origin of products within an association. Even if the association is geographically based or has specific standards for membership, other associations from the same region with different standards or features can coexist without confusing consumers about the origin of the trademark. A regionally based collective mark, such as a GI, not only indicates the origin of the product but also serves as a brand. Protecting GI products as “collective marks” within the trademark system opens up the possibility of using the international Madrid System, administered by WIPO, to file international trademark registrations after registration in the home country. The Madrid System offers a convenient and cost-effective solution for registering and managing trademarks worldwide. By filing a single international trademark application and paying one set of fees, protection can be sought in up to 131 countries. However, it is important to note that marks are vulnerable to revocation if they have not been used in a real and effective manner within a certain period after registration, often five years.

– To safeguard products with geographic reputations, constant monitoring of the GI Journal of other countries, particularly of those having shared borders with Bangladesh, is necessary to prevent wrongful registration of GIs for Bangladeshi products.

– In case of any GI conflict with another nation, bilateral consultations and legal recourse should be pursued.

– In alignment with Articles 22-24, Part II, Section 3, of Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), each WTO member has an international obligation to ensure that a GI product genuinely originates from their territory. If there is confusion about the geographical origin, the concerned members should seek a mutually agreed upon solution.

– If a GI is believed to be wrongfully appropriated by another nation and bilateral negotiations cannot resolve the issue, an appeal can be made to the High Court for its cancellation. Upon receipt of an application in the prescribed format from any aggrieved party, the Registrar or the High Court has the authority to issue an order to cancel or vary the registration of a GI based on “any contravention or failure” to observe a condition entered on the register in relation to the GI.

– Indeed if bilateral consultations and legal recourse through the country court system do not work, the case could be taken to the WTO dispute settlement mechanism (which remains dysfunctional at the moment due to the absence of an adequate number of judges) under a possible TRIPS Agreement violation.

– To protect trans-border GIs effectively across borders, Bangladesh and India need to adopt a collaborative approach instead of a competing one based on shared understanding and mutual consultations. A joint binational approach for exploiting trans-border GIs would be the best commercial strategy to enhance the recognition and value of the shared resources of both countries in international markets.

– While there is a long way to go in establishing a system for shared protection of trans-border GIs, it is recommended that Bangladesh sign a regional agreement with the EU if it hasn’t yet and accede to the Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement (2015). Subsequently, through mutual understanding between the two neighbouring countries, potential avenues for joint protection should be explored.

– Once both Bangladesh and India sign up for the Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement 2015, discussions can be initiated on submitting joint applications under the act for all trans-border GIs since the accession of the EU to the Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement means that as soon as any third country joins the agreement, their GIs will gain protection throughout the EU as well through the Lisbon system.

– To secure and reap the benefits from GI recognition, the government’s role is necessary, but the role of producers is inevitable. Although 28 GI products have been registered in Bangladesh, none have been exported with the GI tag, indicating a failure on the exporters’ part. Eligible businesses must contact the GI owner organisations to benefit from premium export prices.

– Furthermore, it has not been decided who will approve the GI tags to be used by exporters. The relevant government authority needs to address this issue.

– Producers must be vigilant to ensure that no one unlawfully registers a GI for their products within the country or in neighbouring jurisdictions.

– Commercialisation is required, but the downstream distribution of benefits is also a concern. It must be ensured that GI protection has the potential to improve the conditions of farmers and rural producers, who often do not see the benefits of intellectual property protection in a globalised world.

There is much work to be done before Bangladesh can reap the benefits of any GI registration and effectively safeguard its GIs. By implementing these recommendations, Bangladesh can better protect its GIs, resolve conflicts, and maximise the economic and cultural benefits of its unique products.

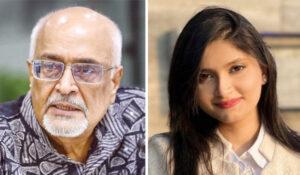

Debapriya Bhattacharya is distinguished fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD). Naima Jahan Trisha is currently working as a Research associate at CPD.