Published in Economic & Political Weekly on Saturday, 9 July 2016

Birth of Bangladesh

Recollections of a Politician Economist

Habibul Haque Khondker (habib.khondker@gmail.com) is a professor of sociology at Zayed University, Abu Dhabi, UAE.

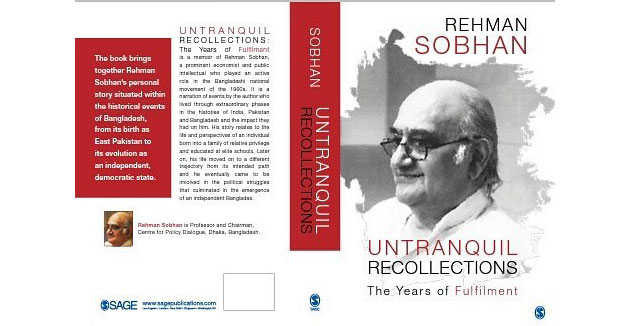

Untranquil Recollections: The Years of Fulfilment New Delhi: Sage, 2016; pp 445,₹450 (paperback).

Rehman Sobhan, the author of this book, describes himself as a “politician economist” who became a combatant, not at battlefield, but in the arena of diplomacy and international politics. During the liberation war of Bangladesh, Sobhan had a role in drafting the Proclamation of Independence—a draft that he worked with Barrister Amirul Islam in Delhi where he inserted “Peoples” before the “Republic of Bangladesh.” Sobhan justified the insertion by stating that the independence of Bangladesh would be the culmination of the struggle of the people.

Rehman Sobhan, the author of this book, describes himself as a “politician economist” who became a combatant, not at battlefield, but in the arena of diplomacy and international politics. During the liberation war of Bangladesh, Sobhan had a role in drafting the Proclamation of Independence—a draft that he worked with Barrister Amirul Islam in Delhi where he inserted “Peoples” before the “Republic of Bangladesh.” Sobhan justified the insertion by stating that the independence of Bangladesh would be the culmination of the struggle of the people.

Sobhan was also at hand in introducing and vouching for the credentials of Tajuddin Ahmed, the would-be Prime Minister of Bangladesh to the Indian political elite. He knew some of the key economists in Delhi at that time, Amartya Sen and Ashok Mitra—they introduced him to P N Haksar, Principal Secretary to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Sobhan was both the ultimate fixer and the go-between in those crucial moments in the history of Bangladesh.

Sobhan played a key role in laying the economic basis of a nationalist struggle. He took Bangladesh’s cause to London, Washington, Paris and Rome, pleading and cajoling the World Bank, and other donors, opinion-makers, and powerful politicians to look at the unfolding tragedy from his country’s standpoint. Sobhan has multiple identities. A quintessential public intellectual, a freedom fighter, an “Envoy Extraordinaire in charge of Economic Affairs” (p 409), a confidant of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (like most Bangladeshi nationalists, he adoringly refers to him as Bangabandhu) in the formative phase of the nationalist movement, an inspiring professor, a caring mentor, a journalist, an institution builder, a food aficionado, a sports enthusiast, and a connoisseur of music. When such a multivalent personality, a legend in his own rights, writes his memoirs, multiple twists, strands and dimensions are natural. It is difficult to find a point of departure.

With Politicians and Intellectuals

Let us start with a photograph in the middle of the book under review (before page 232) where Rehman Sobhan as a young student is seen with some of the most distinguished politicians, business tycoons and future academics and journalists of South Asia. Jawaharlal Nehru and Swaran Singh, along with others, are seen with young Sobhan, the then president of Mazlish, a platform for the South Asian students at Cambridge. There is another photo of him running a marathon at St Paul’s school at Darjeeling. Sobhan‘s marathon of a long public life is yet to end. His friend’s circle at Cambridge days included Amartya Sen, Mahbub ul Haq and Manmohan Singh, among others and his teachers included Joan Robinson, Peter Bauer, Maurice Dobb and other luminaries. The network of economists was probably the only network that existed in South Asia in the 1960s and early 1970s; this network played a crucial role in the early phase of the liberation war.

Sobhan and Anisur Rahman, a fellow economist at Dhaka University, crossed into Agartala in disguise following the military crackdown that was launched on the night of 25 March 1971. This was a perilous journey during which Sobhan was mistaken as a non-Bengali, and was about to meet popular justice. Fortunately for him—and for Bangladesh—he was spared when two students of Dhaka University vouched for his identity. Sobhan was in jeopardy for his lack of facility in Bangla, a hallmark of the Bengali Muslim elite, many of whom spoke only Urdu and English.

Days and Nights in Kolkata

Sobhan was a product of an elite class; his father trained at Sandhurst and later served as a top police officer in Kolkata, and his mother belonged to the Dhaka Nawabi family, which he refers to as DNF. (Sobhan has a penchant for abbreviations.) He was sent to a boarding school in Darjeeling at a very young age. At the boarding school, he was noticed for his eloquence, brilliance in classroom and leadership qualities, especially in sports. He was a man of enormous self-confidence. He once asked President Yahiya Khan of Pakistan why there was no Bengali economist at the top echelon. Khan, perhaps in half jest, asked him to fill the vacuum.

Sobhan has fond memories of his childhood that alternated between the spartan conditions of boarding school and a carefree lifestyle in Kolkata household. His loving, perhaps somewhat indulgent mother used to take him (he was eight years old then) to a movie show in New Empire, Metro or Light House where new Hollywood movies would be screened. In one such instance in early 1943 a newsflash alerted the viewers about bombs dropping in Kolkata. Sobhan writes: “My mother was not one to be deterred from watching a good movie to its conclusion merely by a few Japanese bombs” (p 33).

A good part of the book reminisces about Kolkata, his birthplace and a city where he grew up amidst great affection. The narrative brings the sights and sounds of Kolkata of the 1940s alive and one can almost smell the chicken tikka of Nizams or fried bhetki at Firpo. A foody and a film buff, he spent his halcyon days in Kolkata.

Sobhan admits his ignorance of the developments leading to the partition of India and the attendant nationalism and bloodletting when he was at St Paul’s busying himself with academic and sporting pursuits. He was barely 12 at that time. But as he began to grow up, Sobhan’s commitment to the social causes and his empathy for the downtrodden were abundantly clear by his option to teach at the Dhaka University, the center-point of the nationalist struggle.

A Professor with a Cause

Through his family connections, Sobhan knew some of the stalwarts of politics. His paternal uncles included the finance minister of the princely state of Bhopal and the Chief Justice of Pakistan’s Supreme Court. Hussain Saheed Shurwardy, the chief minister of undivided Bengal was his wife’s uncle. His maternal grandfather Khwaja Nazimuddin too held the position of chief minister of undivided Bengal from 1943–45. He went on to become the chief minister of East Bengal, governor general and later Prime Minister of Pakistan. It was at a dinner hosted by Nazimuddin that Sobhan first met Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1957. Sobhan does not provide full disclosure to his well-connected family.

The privileged connections did not stand in his way; rather he leveraged them in his pursuit to become an indefatigable fighter against exploitation and injustice. Widely admired as an articulate voice of the downtrodden, Sobhan identified with the cause of the Bengalis in their struggle for social justice. Regional disparity overlaid an exploitative social structure where the Bengalis, the numerical majority in Pakistan, were on the receiving end of exploitation, humiliation and discrimination. Sobhan cast his lot with the aspirations of the ordinary Bengalis whose extraordinary courage and resilience deeply impressed the Cambridge University graduate, who had become a reader at the Dhaka University.

Characteristic Humility

Sobhan narrates his life story without taking credit for any of his achievements. But it is difficult to deny the imprint of a humanist, a scholar with a heart for the downtrodden on his students, many of whom played—and continue to play—a decisive role as politicians, public officials and civil society activists. The “two-economy theory,” the backbone of the Six-Points that provided the basis for the movement of political and economic autonomy from Pakistan under the leadership of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, is attributed to him. Yet Sobhan deflects credit by sharing it with a group of Bengali economists whose nationalistic aspirations were bred in the context of Pakistani economic exploitation. In his book Basic Democracies, Works Programme and Rural Development in East Pakistan (1966), he launched the first intellectual salvo on the authoritarian rule of Pakistanis. The book was a painstaking, politico-economic analysis of rural development which was underwritten by food aid under PL480 and the Pakistani government under Ayub Khan.

With his cousin Kamal Hossain, Sobhan organised fellow intellectuals to set up a discussion group, the National Association for Social and Economic Progress (NASEP). This soon became a think tank, where like-minded nationalists discussed problems economic disparity, issues of education and authoritarian politics of Pakistan. The young academics were spirited, highly educated, nationalists yet cosmopolites, who sought to forge linkages with political parties which led to the formation of Janamaitri Parishad (JMP) in 1962.

As a young economist, he was questioning the older economists, mostly Pakistani, about regional disparity. His constant probing and questioning gave him notoriety but also rightful exposure within the circle of the economists. However, his reputation was anchored in his contributions to newspapers where he sought to mobilise the intellectual class who read the English dailies. Sobhan along with Kamal Hossain and Hameeda Hossain brought out a weekly magazine Forum from 1969 to 1971, which published some of the most penetrating analyses of the political economy of Pakistan and provided a blueprint for the nationalist struggle. As a journalist he quickly caught the imagination of the intelligentsia and attention of the authority. He was sought both by the nationalist politicians as well as by the Pakistani intelligence community.

An Accidental Diplomat

On 27 March 1971 Sobhan, then an economics professor at Dhaka, left home for India. His own fate was as uncertain as that of Bangladesh, he recollects in this memoir subtitled The Years of Fulfilment. Lincoln Chen, an American professor and a friend of Bangladesh in a review of Sobhan’s book in the Hindu (28 February 2016) wonders, “why fulfilment?”

Fulfilment for Sobhan was seeing Bangladesh’s liberation, a dream that finally materialised on 16 December 1971, which he saw from his temporary house at Oxford on TV with a broken ligament sustained at the United Nations (UN) building in New York. Until 15 December 1971 Sobhan, an officially anointed “envoy extraordinaire” by the Mujibnagar government, lobbied hard at the UN. He moved from lawmakers’ offices in Washington DC to persuade them to support the cause of Bangladesh.

Sobhan’s journey began in 1957 when a 21-year Cambridge graduate landed in Dhaka. He called Bangladesh home, even though his facility with Bangla language was almost non-existent. His power of articulation in English is exceptional. But the gift of gab that Sobhan honed in his school days at St Paul’s, Darjeeling, Aitchison College, Lahore, or Cambridge where he was the president of Majlish, came handy in his role of an envoy for a country yet to be born. His Cambridge connections helped Sobhan establish linkages with an international old boy network some of who were economists and other prominent journalists.

Though, he met Mujib along with Chief Minister Ataur Rahman at the residence of his maternal grandfather, Khwaja Nazimuddin in 1957, it was not until 1964 that Sobhan developed a close relationship with the founder of future Bangladesh. That year, Mujib invited Kamal Hossain and Sobhan to help draft the manifesto for 1964 elections. When Ayub Khan declared his candidacy for the 1964 elections and issued a list of his achievements, Mujib asked the duo to contribute to the drafting of his response. Sobhan fondly recollects Sheikh Mujib’s greatest quality to reach out to people and draw upon their perceived qualities at the service of the nation.

Sobhan’s memories take the readers to so many untold stories of the challenges of the liberation war, the intrigue in Kolkata between the Mujibnagar, 8 Theatre Road and the Bangladesh foreign Ministry at Park Circus where Mushtaq and his gang were conspiring with the US officials. His narratives vividly record the story of sacrifice and commitment of so many, who cast their lot with the cause of Bangladesh. Americans, Indians, British, French academics, philosophers and ordinary men and women were able to make the choice in favour of justice. Some made the right choice on their own, others needed little persuasion.

Sobhan was one of the few who had an audience with Sheikh Mujib only hours before his arrest on 25 March 1971 along with Mazhar Ali Khan, a Pakistani journalist with links to Bhutto’s Peoples Party. To whom Sheikh said, “they may kill me, but an independent Bangladesh will grow on my grave.” Sobhan chronicles some of the most crucial days leading to the launching of genocide by the Pakistani military on 25 March 1971. Following the abrupt postponement of the inaugural session of the constituent assembly on 1 March 1971 Bangladesh, what was then East Pakistan, exploded in protest. The elections of December 1970 gave the Awami League of Sheikh Mujib a mandate to become the Prime Minister of Pakistan as it won 160 of the 162 seats in the 300-seat parliament in a free and fair national election. The postponement of the parliamentary session sine die by President Yahiya Khan was taken as an act of betrayal.

Sheikh Mujib reacted sharply, but judiciously, declaring a non-violent, non-cooperation movement immediately which led to civil servants, and business communities pledging support and allegiance to Bangabandhu. From 5 March onwards, Sobhan notes, “the call of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman repudiated the political authority of the Pakistani government within the territory of Bangladesh. This political authority was never restored” (p 330). The transference of authority from the military-ruled Pakistan to Bangabandhu on 5 March “renders contemporary political discussions on the declaration of independence both mindless and pointless” (p 330). Sobhan along with Nurul Islam, Tajuddin Ahmed and Kamal Hossain were instrumental in running the day-to-day functions of the government in those fateful days.

The memoir ends on the last day of December 1971 when Sobhan returned to Dhaka after accomplishing his mission. His memoir provides a window to the complicated political and diplomatic processes of the background of the war of independence and the historical antecedents that led to the birth of a nation. The process, surely, was untranquil. In the early days of April 1971 in Delhi, Sobhan was prescient as he wrote in the Declaration of Independence, a document that accompanied the Proclamation of Independence, “Pakistan lies dead and buried under a mountain of corpses” (p 368).