Originally posted in The Daily Star on 21 May 2023

Private investment falls for second time in 3 years

The private investment-to-GDP ratio in Bangladesh declined in the current fiscal year owing to a lower confidence among investors amid the persisting dollar crisis and global uncertainty, higher inflation and a fall in demand for goods in international markets.

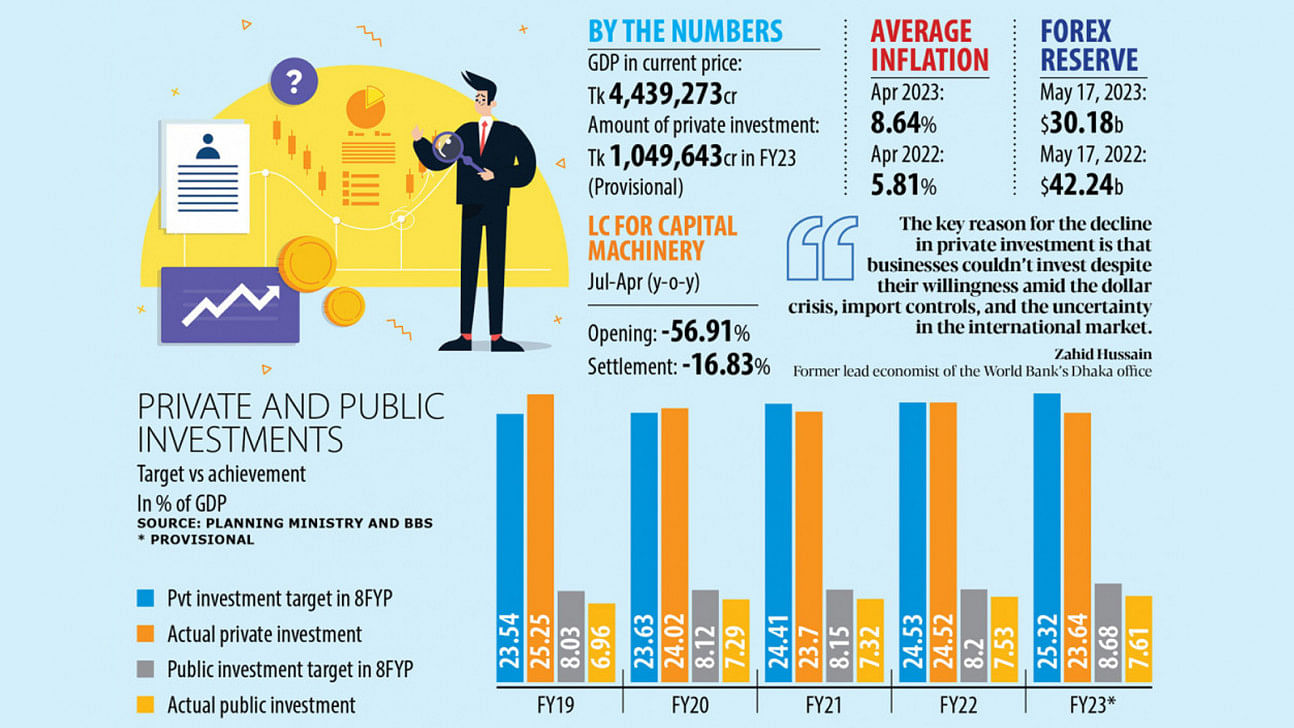

The private investment-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratio declined by 0.88 percentage points to 23.64 per cent in 2022-23, provisional data from the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics showed.

This is the second fall in the ratio in three years.

Usually, private investment either remains unchanged or slightly increases in a fiscal year compared to the preceding year. However, it witnessed a slight decline in 2020-21 owing to the impacts of Covid-19.

In keeping with the recovery of the economy from the health crisis, the ratio rebounded strongly in 2021-22, rising 0.82 percentage points to 24.52 per cent.

During the peak of the pandemic, the global economy suffered and Bangladesh was no exception. As Covid-19 cases started to drop, the economy of Bangladesh returned to its higher growth trajectory as the world economic outlook brightened, pushing up imports to meet both local and global demand.

But following the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war in February last year, the country’s foreign reserves came under huge pressure, prompting Bangladesh to initiate some import control measures to save the reserves.

The reserves slipped to $30.18 billion on May 17 this year from $42.24 billion on the same day a year earlier, a decrease of about 28.50 per cent.

According to Zahid Hussain, a former lead economist of the World Bank’s Dhaka office, the key reason for the decline in private investment is that businesses couldn’t invest despite their willingness amid the US dollar crisis, import controls, and the uncertainty in the international market.

“Businesses that had planned to set up new industrial units couldn’t do so because of the constraint they faced while importing machinery for the dollar crisis.”

The dollar crisis has persisted for almost a year since earnings from remittance and exporters did not offset the surge in import bills, causing an erosion in the reserve.

Thus, the opening of letters of credit for capital machinery slumped 56.91 per cent and settlement dropped 16.83 per cent in the July-April period of FY23 compared to the same period in the previous fiscal year, Bangladesh Bank data showed.

The uncertainty in investments that deepened since the introduction of China’s zero-covid policy is still lingering, according to Hussain.

“In the past, the investment-to-GDP ratio would either remain flat or witness growth. It did not fall.”

Higher inflation is another factor behind the lower investment.

Average inflation shot up to 8.64 per cent in April from 5.81 per cent in the identical month last year, driven by higher commodity prices.

“Inflation has always been recognised as unfriendly to investments and it makes it difficult for businesses to project profits and losses. So, investors have adopted a wait-and-see approach,” Hussain said.

Hussain thinks the $4.7-billion lending programme of the International Monetary Fund might give a boost to the confidence level of investors to some extent, but restoring confidence to the pre-crisis level will depend on the result of the programme.

Professor Mustafizur Rahman, a distinguished fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue, says the drop in private investment gives a negative signal about the economy.

“The stalling investment scenario also reflects the decline in the growth of GDP and imports.”

The economy is estimated to have expanded by 6.03 per cent in 2022-23, according to the BBS. The GDP grew by 7.1 per cent in 2021-22.

Rahman said exports could not meet the targets in the first 10 months of FY23 and there was even negative growth in shipments in March and April.

“So, it will have a negative impact on the economy in terms of GDP growth, employment generation and income augmentation.”

He blamed structural problems, apart from the dollar crisis, an elevated level of inflation and the gloomy global economic situation, for the lower private investment.

Structural constraints include the cost of doing business, absence of a sound investment environment, and the failure to deliver an effective one-stop service, according to Rahman.

Private investment had been stagnant at around 23 to 24 per cent of GDP for about a decade before the pandemic, as a shortage of skilled labour, opaque regulations, and limited credit availability outweighed discretionary government incentives, said the World Bank in April.

The incentive to defer investment has increased with rising global uncertainty, higher capital goods prices, an unpredictable domestic forex regime, energy shortages, and political uncertainty ahead of upcoming elections, it said.