Originally posted in The Business Standard on 11 June 2024

One can safely say that these are not the last incidents. Shouldn’t Bangladesh be looking for a predictable legal solution to the issue of shared geographical resources?

The Recurring Issue

It has happened again. As the backlash from the controversy over the Geographic Indications (GI) awarded to India for Tangail Saree begins to simmer down, a new concern has emerged.

It may be recalled that on February 1, 2024, India’s Ministry of Culture announced that the West Bengal State Handloom Weavers Co-Operative Society secured the GI status for ‘Tangail Saree’.

This move triggered outrage and criticism from a large cross-section of Bangladeshi citizens. Following the public outcry, the Bangladesh government has also gone ahead with national GI registration, as well as legal initiatives concerning the product.

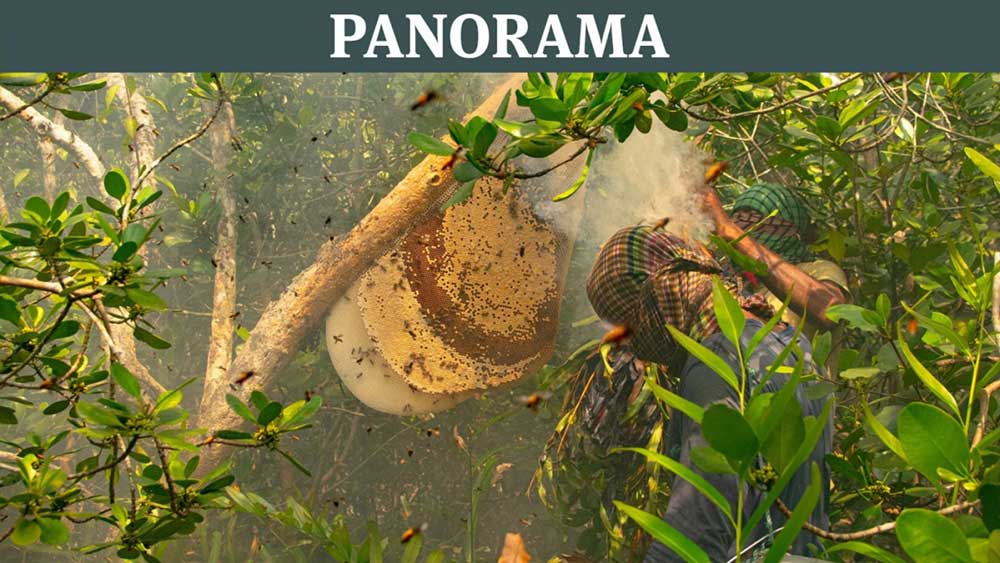

At the recently held Diplomatic Conference on Genetic Resources and Associated Traditional Knowledge organised by The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) in Geneva (May 13-17, 2024), Sundarban Honey was displayed as a GI product of India.

This information came to light through a tweet by the West Bengal Forest Department on May 16 2024, declaring that ‘Sundarban Honey is the only GI product from West Bengal selected for Display’ at the Conference.

This sole representation of the said product by India sparked questions in our minds, as the majority of Sundarban’s territory lies within Bangladesh. Indeed, Bangladesh is the primary extractor of Sundarban honey.

While official government records could not be found, media reports indicate that about 200-300 tonnes of Sundarban honey are extracted annually, while India produces about 111 tonnes per year, as mentioned in its GI application.

Bangladesh government’s Department of Patent, Designs and Trademark (DPDT) under the Ministry of Industries, on its website, has listed 31 GI products of Bangladesh as of April 30 2024. This list does not include the Sundarban honey.

Curiously, the district administration of Bagerhat filed an application for the GI tag of Sundarban Honey six years back, on August 7, 2017, and there has been no development since then. This is a rather astonishing example of administrative dereliction of duty!

Thus, the GI of Sundarban honey in Bangladesh has remained unsecured. In contrast, West Bengal Forest Development Corporation Limited applied for GI rights for Sundarban Honey on July 12 2021, and the GI tag was issued on January 2 2024.

There are a number of products shared between India and Bangladesh that are registered as GIs in both countries. These include ‘Nakshi Katha’, a traditional embroidered quilt that originates from Jamalpur in Bangladesh, Khirsapat mangoes from Chapainawabganj, Fazli mangoes from Rajshahi and Chapainawabganj, and Sundarban honey from the Sundarbans, a mangrove forest shared by both countries.

All these products are also found and registered as GIs in India with the titles ‘Nakshi Kantha’, ‘Malda Khirsapati (Himsagar) Mango’, ‘Malda Fazli Mango’, and ‘Sundarban Honey’ under the jurisdiction of West Bengal.

In addition, Dhakai Muslin, a handwoven fabric, has its roots in Dhaka, but India has registered a GI for Muslin as well, under the title ‘Bengal Muslin’. Such is the case for the intricate Jamdani Saree, which also finds expression in Andhra Pradesh, registered as ‘Uppada Jamdani Sarees’ in India.

One can safely say that these are not the last incidents. Shouldn’t Bangladesh be looking for a predictable legal solution to the issue of shared geographical resources? In the subsequent part of this article, we attempt to explore those options.

The legal framework for shared GI

As is known, a trans-border GI ‘originates from a geographical area which extends over the territory of two adjacent Contracting Parties’. Given the contingency of geographical proximity and shared natural resources, it is now obvious that we need to find a mechanism to have shared GIs as global members have for this purpose.

The prerequisite for any country to protect its origin-based traditional products is to register them first in the country of origin. Thereafter, protection can be sought internationally in other jurisdictions by means of bilateral agreements or the Lisbon Agreement for the Protection of Appellations of Origin and their International Registration 1958.

The Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement on Appellations of Origin and Geographical Indications was adopted on May 20 2015, by revising the pre-existing Lisbon Agreement. Although the number of signatories to this act is still limited with only 44 countries, it could be an important first step for extending the supranational protection of GIs alongside the AOs.

Since the EU has acceded to the Geneva Act, EU-registered Protected Geographical Indications (PGIs) and Protected Designation of Origin (PDOs) are also protected by other signatories of this agreement.

The act further allows contracting parties to jointly apply for the registration of AOs/GIs originating from trans-border geographical areas through a common competent authority. States that are parties to the Paris Convention or members of the WIPO with compliant legislation can accede to the Geneva Act.

As members of the Paris Convention, both Bangladesh and India are eligible to join. However, neither Bangladesh nor India has acceded to the act as of now.

Within the European Union’s (EU) system of intellectual property rights, non-European product names can also be registered as GIs, if their country of origin has a bilateral or regional agreement with the EU. Such agreements include mutual protection for these names, allowing the non-EU countries to claim exclusive rights over the product.

We could not trace whether Bangladesh has signed any such contract with the EU at all. Additionally, two countries can submit a joint application for the PGI status of their shared resources under the EU’s GI scheme. Darjeeling and Kangra Tea are the two PGIs of India that have been included in the EU register.

Furthermore, both India and Pakistan have separately published journals before the EU’s Council on Quality Schemes for Agricultural and Foodstuffs for the PGI right over Basmati rice. However, neither country, as of now, has been granted this right.

In alignment with Articles 22-24, Part II, Section 3, of Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), each WTO member has an international obligation to ensure that a GI product genuinely originates from their territory. If there is confusion about the geographical origin, the concerned members should seek a mutually agreed upon solution.

As per WIPO, when geographical indications are assigned to ‘homonymous products’ or shared resources, honest use of GI can be possible across countries provided that ‘the indications designate the true geographical origin of the products on which they are used.’

It is worth noting that in some instances, India did not specify the place of origin in the GI title (e.g. ‘Nakshi Kantha’), while in others, the designated geographical origin mentioned in the GI title did not fall within India’s demarcation (e.g. Tangail Saree of Bengal).

The global experience

The issue of trans-border GI protection is a novel area in the multilateral sphere and more attention should be paid to this issue in WIPO and the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Trans-border GI conflicts are not necessarily common, but they have occurred around the world. Issues arise when producers from different countries claim GI protection for similar products with overlapping geographical areas or historical connections. We recall below some instances from the global experiences.

The conflict between Chile and Peru over the Pisco brandy stands out as a prominent example of trans-border GI disputes. Chile initially secured protection for its Pisco in the EU through a bilateral agreement in 2002, but Peru later joined the Lisbon Agreement and obtained international registration for Pisco.

Consequently, the EU member states were obligated to protect the Peruvian Pisco GI as well. The EU resolved this conflict by designating a PGI to Peruvian Pisco, while still allowing Chile to use Pisco for its brandy under a PDO.

While some countries recognise both Chile and Peru’s claim to Pisco (e.g. United States, Canada, China, and the European Union), others support Chile’s exclusive right to the appellation (e.g. Japan, Australia, New Zealand and Mexico).

India, along with Nicaragua, Cuba, Panama, Venezuela, and Colombia, supported Peru’s claim to the name.

This ongoing dispute has resulted in significant costs for both countries as they have to engage in legal battles in every market a Pisco brand attempts to enter. The prolonged conflict highlights the need for mutual recognition, which would give Pisco a fighting chance to compete with other liquors on the global market.

Hungary and Slovakia have been fighting for years over who can call their wine ‘Tokaj’. An agreement between the two countries in 2004 allowed some Slovak wine to use the same name, but Slovakia did not follow the agreed standards enshrined in Hungarian wine laws.

While Hungary tried to stop Slovakia from registering ‘Tokaj’ in an EU database, courts sided with Slovakia, meaning both countries can use the name under EU law.

Towards a shared GI covenant

In light of the ongoing disputes surrounding GIs between Bangladesh and India, questions loom over the equitable recognition of trans-border GIs.

Without any established legal framework, tensions may continue to rise between Bangladesh and India regarding trans-border GI protection.

The motive behind seeking such protection is entirely rational from a national perspective. Given the reputation and consumer faith that a GI status brings, it is in the economic interest of both countries to register as many GIs as possible for their traditional products, regardless of the ambiguity of the exact geographical linkage.

However, registering separately under the Sui Generis System of WIPO may make the GI product semi-generic in other countries. This may undermine the ability to command premium export prices as neither country can establish exclusivity over the product (as seen with Basmati rice) and may even result in a loss of protection against imitation.

Furthermore, there will be apprehension about legal disputes if either country attempts to deter the other from entering international markets.

To protect trans-border GIs effectively across borders, Bangladesh and India need to adopt a collaborative approach instead of a competing one based on shared understanding and mutual consultations.

We believe that a joint binational approach for exploiting trans-border GIs would be the best commercial strategy to enhance the recognition and value of the shared resources of both countries in international markets.

While there is no denying that there is a long way to go in establishing a system for shared protection of trans-border GIs, we recommend that Bangladesh sign a regional agreement with the EU if it hasn’t yet and accede to the Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement 2015.

Subsequently, through mutual understanding among the two neighbouring countries, potential avenues for joint protection should be explored.

Furthermore, once both Bangladesh and India sign up for The Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement 2015, discussions can be initiated on submitting joint applications under the Geneva Act for all trans-border GIs, since the accession of the EU to the Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement means that as soon as any third country joins the Agreement, their GIs will gain protection throughout the EU as well through the Lisbon system.

The Prime Minister of Bangladesh is expected to travel to India for a summit-level visit in the later half of June 2024. During this high-level visit, the two neighbouring countries may consider signing a shared GI protection agreement. This can be done by committing to upholding a common standard for shared resources and jointly applying to the EU register or under the Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement 2015.

This collective effort would serve the greater good by safeguarding the integrity of the cultural heritage and preserving the economic interests of consumers as well as the marginal producers who grapple with various adversities for the production of these products in both nations.

The authors of this article are respectively a Distinguished Fellow and a Programme Associate at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD).