Originally posted in The Business Standard on 7 March 2024

A ticking time bomb? Bangladesh’s NEET crisis paints a bleak future

A high NEET (Not in Education, Employment, or Training) rate can spell trouble for an economy, especially when it constitutes primarily the country’s youth

Asim (alias) has dropped out of a reputed private university in Bangladesh. His friends have long since graduated and begun working in various jobs. But Asim is not doing that; all he does is hit the gym and idle away his day – living off his working mother’s salary. He ‘does not feel like working.’

Sara (alias) was studying in Class 8 at a high school in Narayanganj when she met Akash (alias), a student in Class 10 in Tangail. Romance bloomed and they eloped. Within a year, she gave birth to a baby daughter. Now, all three of them are living off the income of Akash’s father. Neither Akash nor Sara work anywhere.

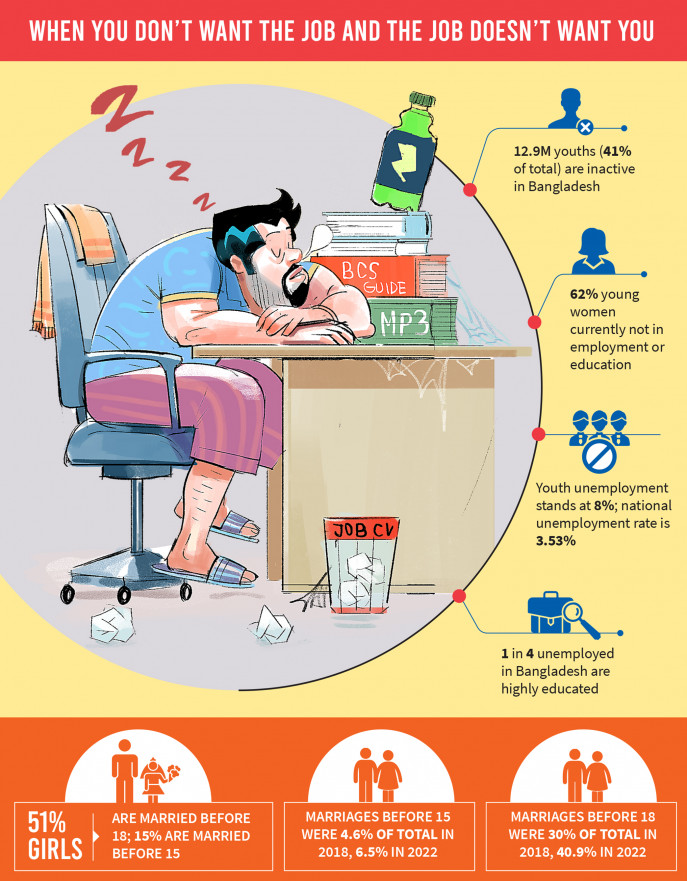

They are not alone. In fact, they are just three of the 41% of Bangladeshi youth who are inactive, totalling about 12.9 million individuals. They are not in the labour force, nor are they actively seeking jobs.

And the situation for Bangladeshi young females is even worse, as 62% of them fall into this category. The statistics paint a grim picture in the backdrop of Bangladesh’s closing demographic dividend window.

Bangladesh now has the highest youth population that it has ever had. With individuals aged 15 to 29 years accounting for approximately 28% of the total population, the country should have been looking at a brighter future. Instead, we have a major population sinking into depression and frustration.

According to BBS statistics, the unemployment rate among young people is the highest in the country. While the national unemployment rate is around 3.5%, the unemployment rate among young people is 8%. The higher the education level, the higher the unemployment rate. The unemployment rate among the highly educated is around 12%. One in four of the total unemployed in the country is highly educated.

There’s a word for this phenomenon

NEET means ‘Not in Education, Employment, or Training.’ It means that a section of the workforce is unemployed and not actively seeking work. This includes individuals who have not returned to school after discontinuing their studies, or those who have not started any form of formal education yet.

A high NEET rate can be indicative of several underlying issues, such as lack of access to quality education, limited job opportunities or societal barriers to employment. This is especially concerning in the context of Bangladesh’s demographic dividend, where a large youth population has the potential to drive economic growth but, based on the statistics, faces significant challenges in entering the workforce.

Bangladesh’s recent BBS Census and Household Census Report-2022 paints a concerning picture of youth inactivity. It says among approximately 31.6 million young people (aged 15-24), 40.67% are classified as inactive, meaning they are NEET.

This finding is further supported by the 2022 BBS Labour Force Survey, which reports a 22% inactivity rate among individuals aged 15-29. While slight discrepancies exist between these surveys due to differing definitions of ‘inactive,’ both paint a clear picture of a significant and concerning NEET population among Bangladesh’s youth.

The studies also show that 61.71% of the educated females are NEET.

What does an inactive youth population mean

Dr Khondaker Golam Moazzem, the Research Director at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), thinks that the country is missing out on valuable potential due to the high NEET rate.

“The demographic dividend, which we could have used to increase our economic growth, can not be utilised due to such high youth inactivity.”

Idle youth may be more susceptible to social ills like crime, drug abuse and extremism. This can further strain the social fabric and hinder overall societal progress. Dr Moazzem said, “The ones who become part of the teen gangs are mostly the inactive youth, and the anti-social activities have a large social cost.”

At the same time, the negative consequences of a high NEET population can be perpetuated across generations. When young people are not equipped with the necessary skills and education, they may struggle to find decent employment, leading to a cycle of poverty and limited opportunities for their children as well.

The socio-economic consequences of the unaddressed NEET crisis can be long-lasting and detrimental.

Underlying causes

For one, skill mismatch has been rampant in the labour force, and it has contributed greatly to the inactivity of the youth. Due to a lack of proper training, they cannot enter the workforce, turning into NEET.

Dr Zahid Hussain, the former lead economist of the World Bank’s Dhaka office, pointed out the failure of the education system to create a skilled labour force out of our youth.

“Many young graduates cannot enter the labour force as the skills they have been taught at the educational institutions are not enough to get a job. The mismatch has created a paradoxical problem. The youth are saying – We are not looking for jobs because there is no job for us. The employers are saying – We can not hire new people because they do not have the skills. So, there is a supply of skills with no demand; and there is a demand for skills with no supply.”

Tasmiah Rahman, the Associate Director of BRAC and Head of Programme, Skills Development, has the same opinion regarding the matter.

“There are not enough jobs to absorb the new people joining the labour force each year. Our economy does not have the capacity.”

Meanwhile, as the companies have to hire foreign executives to fill the highly skilled posts, it is costing the country valuable foreign currency.

Dr Moazzem pointed it the same as well. “If our youth could be trained and educated for such highly skilled jobs, then we would not have hired foreign professionals at such high expense. We could have saved our foreign currencies.”

There is another issue at play here. The societal expectation of a ‘good job’ has shaped the youth’s perception of job seeking. The so-called ‘white collar jobs’ are highly valued in society, so whenever an educated youth does not get such jobs, they get frustrated and discouraged. And since the ‘blue-collar jobs’ are demeaned and looked upon, they cannot take any high-paying blue-collar jobs like technicians or mechanics.

“Society has failed our youth,” Dr Zahid Hussain said. “It is not just their fault. Since childhood, they have been taught that they must be engineers, doctors, officers or bureaucrats. But not everyone can become one, and so whoever does not get such a job, they give up.”

Additionally, early marriage has been another important reason behind the lack of female labour force participation. Child marriage is on the rise; 51% of girls in Bangladesh are married before their 18th birthday and 15% are married before the age of 15.

In 2022, marriages before 15 spiked to 6.5%, up from 4.6% in 2018. Shockingly, 40.9% of girls were married before turning 18 in 2022, compared to 30.0% in 2018, marking an alarming annual average increase of 2.18 percentage points. When such an alarming trend is rising in Bangladesh, it is going to affect the overall youth participation in the labour force.

What are they exactly doing?

Tasmiah Rahman also thinks that the perception of ‘good jobs’ has pushed many youth to pursue government jobs or formal jobs only, instead of taking up more technical jobs. And this has created a skill mismatch in the job sector.

At the same time, Rahman has a different point of view regarding the data. She pointed out the fact that there is a huge informal economy in Bangladesh, and it is not represented in the data.

“Whenever a young person drops out of school, he or she joins the informal sector of the economy,” she said, “But the informal economy is not counted in the statistics. So, they are included in the NEET.”

It is clear that while one-third of Bangladesh’s population falls within the youth demographic (15-35 years old), signifying a demographic dividend, this large youth cohort does not automatically translate to accelerated development. Inadequate access to quality education and a skills gap further disadvantage young people in the labour market.

Such statistics, of a highly inactive youth population, make us question the effectiveness of government policies regarding our youth, because almost half of young people remain outside the workforce.

Bangladesh must prioritise empowering its youth by equipping them with the physical and intellectual skills needed to maximise their potential and drive national growth and prosperity.