Originally posted in The Financial Express on 26 December 2023

The banking sector in Bangladesh has encountered numerous challenges over an extended period. Its weaknesses have been consistently exposed through high loan default rates and subpar performance across various indicators. Bangladesh’s banking sector has consistently demonstrated vulnerability, primarily because of a lack of good governance and a dearth of reforms. This inherent fragility presents significant risks to the overall economy. Regrettably, the government’s commitments to safeguard the banking sector remain unmet. Considering recurrent instances of fraudulent activities and irregularities, the actions implemented by the government have been insufficient. Non-performing loans (NPLs) remain unchecked, threatening the health of the country’s financial system. Crony capitalists have used banks as vehicles for reaching their goal of financial oligarchy. Unfinished financial sector reforms are holding back the improvement of the economic outlook. This section briefly presents the performance of some key indicators in recent periods and makes a few recommendations to overcome the challenges.

Instances of reported irregularities in banks: During the last several years, the banking sector has encountered several irregularities perpetrated by numerous business conglomerates and individuals, resulting in the misappropriation of substantial sums of money from several banks, amounting to thousands of crores of taka. CPD has compiled published news reports of 24 major irregularities in the banking sector from 2008 to 2023, which add up to an astronomically large amount of more than BDT 922.61 billion or more than BDT 92,261 crore.

The potential recovery of the aforementioned funds remains uncertain, with the possibility of non-recovery looming large and a plausible scenario involving the funds being illicitly transferred abroad through money laundering activities. Regrettably, instances of lending irregularities have been observed by the relevant authorities. The decision and disbursement of a significant number of loans are made under the guidance and directives of higher authorities within the bank. Loans are observed to be allocated to business groups and individuals in a manner that appears to circumvent established rules and regulations, purportedly under the guidance of influential individuals. The absence of mechanisms to hold loan defaulters accountable for their actions and fraudulent behaviours has demoralised and frustrated honest borrowers. The provision of undue privileges is exclusively reserved for borrowers with substantial loan amounts. Unfortunately, it has been observed that small borrowers have been subjected to legal consequences, including imprisonment, in instances where they fail to fulfil their financial obligations. However, large defaulters continue to remain unscathed.

Implementing effective measures to combat large-scale unlawful lending is often hindered by many of these borrowers either holding ownership stakes in the banks or possessing influential support from powerful entities. The banking sector has exhibited instances of monopolisation, leading to a decline in the governance of the sector. The phenomenon in question has additionally given rise to a form of capitalism called crony capitalism, wherein financial institutions are utilised to extract resources or wealth by a group of people favoured by the authorities.

The current state of the banking industry is precarious as it is plagued by fraudulent activities and irregularities. The incidents indicate a notable lack of proactive measures by the authorities to address the issue and establish a sense of order within the sector. The observed escalation in defaulted loans and ongoing instances of embezzlement within the banking sector failed to demonstrate any urgency on the government’s part in addressing this issue.

Lack of independence of the central bank: The central bank, which has the principal duty of supervising the banking sector, must be able to act with complete independence if it is expected to play any meaningful role in upholding discipline among banks. Bangladesh Bank, the central bank of Bangladesh, has a wide gamut of macroprudential regulations designed to limit systemic risk and reduce the incidence of disruptions in the financial system that may jeopardise the real economy. Broad regulations such as countercyclical capital buffers, capital conservation buffers, limits on leverage ratios and caps on credit growth apply to the banking sector. There are also regulations for the household sector, such as a cap on credit growth to the household sector, a cap on loan-to-value ratio, a cap on debt service-to-income ratio, a limit on amortisation periods, restrictions on unsecured loans and exposure caps on household credit. Corporate lending is regulated by monitoring banks’ indebtedness to large corporate borrowers. The liquidity coverage ratio, net stable funding ratio, loan-to-deposit ratio, cash reserve ratio and statutory liquidity ratio are used to regulate the liquidity position of banks. The central bank also has tools such as the Interbank Transaction Matrix and Bank Health Index, which it uses to examine the threat of systemic risks and financial contagion. Despite being armed with such a potent regulatory arsenal, Bangladesh Bank has been unable to reduce the rise in the volume of NPLs in Bangladesh’s banking sector. This indicates that policies cannot result in favourable outcomes in the absence of good governance and the independence of the central bank.

One may recall, the Central Bank Strengthening Project was initiated in 2003 to establish a robust and efficient banking regulation and supervisory framework. The Bangladesh Bank (Amendment) Act, 2003, was enacted in parliament, granting the central bank the authority to function independently. Regrettably, Bangladesh Bank has progressively lost its autonomy and become weaker over time despite possessing such a mandate. An explicit illustration of how the Bangladesh Bank’s sovereignty is disrupted by the Financial Institutions Division (FID) of the Ministry of Finance (MoF) is observed in the mandate of the FID, which clearly states the primary function of FID is the ‘administration and interpretation of the Bangladesh Bank Order, 1972 (P.O. No. 127 1972) and orders relating to the specialised banks and other matters relating to state-owned banks, insurance and financial institutions’ (MoF, 2017). By asserting this function in its mandate, the MoF has established its authority to oversee the governance of the Bangladesh Bank.

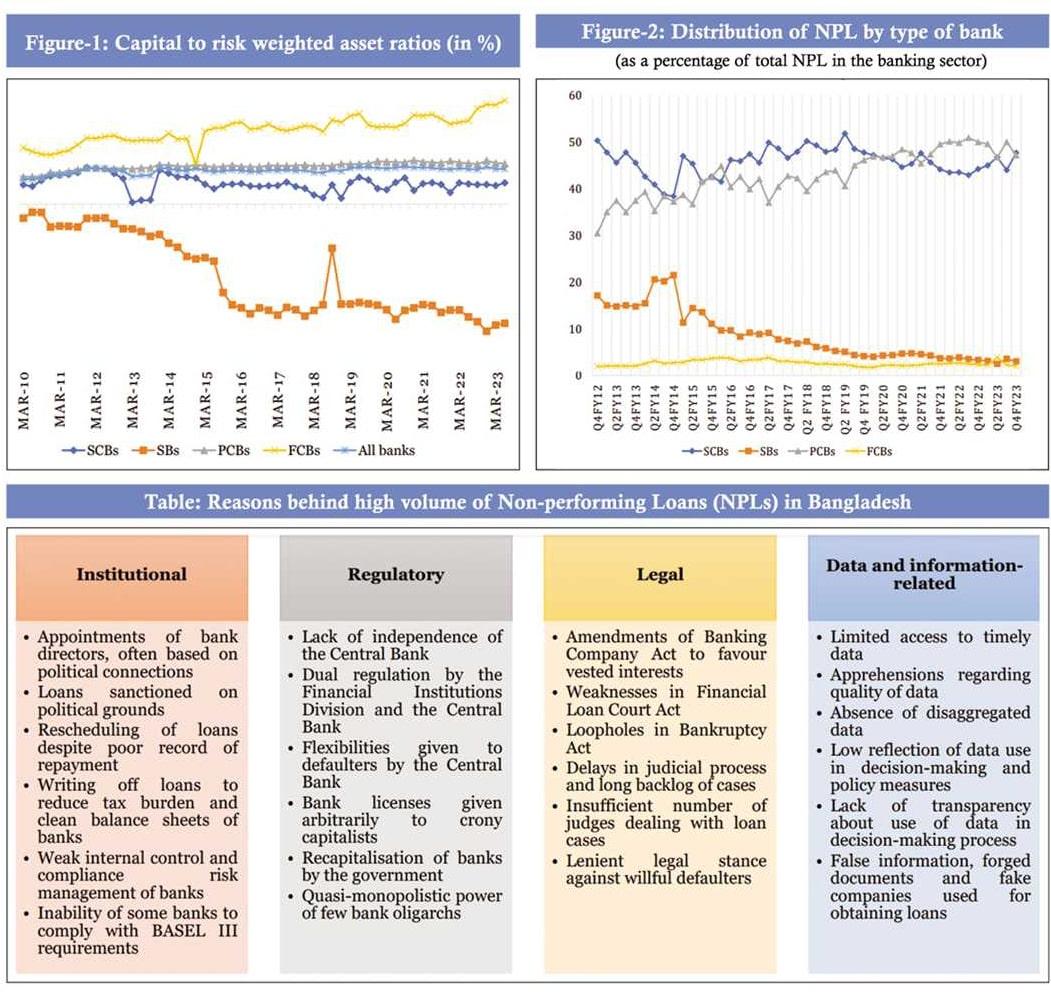

Capital inadequacy of banks: Bangladesh Bank’s Guidelines on Risk-Based Capital Adequacy state that banks must maintain a minimum total capital ratio of 10 per cent (or minimum total capital plus capital conservation buffer of 12.5 per cent) by 2019, in line with BASEL III. However, state-owned commercial banks (SCBs) have failed to maintain minimum capital adequacy requirements for the past ten years (Figure-1). On the other hand, the specialised banks (SBs) have remained critically undercapitalised. Without reducing NPLs, capital adequacy cannot be improved since higher levels of NPLs lead to increased provisioning requirements, which results in capital shortfall.

High volume of non-performing loans (NPLs): NPLs are a direct threat to a country’s financial health and development. NPLs may appear innocuous, occurring merely because borrowers cannot repay loans associated with high interest. However, studies have shown that, in general, high interest rates are not causally related to high levels of NPLs in Bangladesh (Ahmed & Islam, 2006) (Mujeri & Younus, 2009) (Hossain, 2012). For small and medium enterprises (SMEs), high interest rates could be a reason behind NPLs (Jahan, 2016).

The reality is that NPLs originate from uncertainty and corruption, both of which have detrimental effects on the growth of a country’s banking sector (Park, 2012) (Moshirian & Wu, 2012) (Lin, 2012) (Serwa, 2010). Research has shown that the reasons behind the high amount of NPLs in Bangladesh include political instability, corruption, poor governance, and weak rule of law (Banerjee, et al., 2017) (Alam, Haq, & Kader, 2015). Poor management of state-owned commercial banks, coupled with malpractices and corruption, has contributed to the high levels of NPL (CPD, 2018a and CPD, 2018b). Contrary to all established banking norms, state-owned commercial banks (SCBs) have been awarding loans purely on political grounds (Habib M. N., 2017). Consequently, these banks do not routinely assess the potential risks associated with the borrower. Creditworthiness is judged by political worthiness. As a result, having good political connections is perceived to be adequate to obtain large loans. Additionally, the government’s tendency to fund loss-making state-owned enterprises, through SCBs has aggravated the problem of NPLs even further. Research has shown that, on average, only 33 per cent of first-time and 30 per cent of third-time rescheduled loans were recovered during 2011–2014 (Habib M. N., 2017). The study also mentioned that over the same period, loans worth Tk. 455.274 billion were written off by the banking sector. Evidence has also emerged that only 14 per cent of bank officials consider the borrower selection process extremely effective (Habib M. N., 2017).

The total volume of NPL has increased by more than three times in the last ten years, from Tk 427.25 billion in Q4FY12 to Tk 1560.4 billion in Q4FY23. However, actual NPL will be much higher if distressed assets, loans in special mention accounts, loans with court injunctions, and rescheduled loans are included.

Disaggregation of the absolute volume of NPLs shows that over the years, the volume of NPLs in SCBs as a percentage of the total NPL of the banking sector has decreased slightly from 50 per cent in Q4FY12 to 48 per cent in Q4FY23. However, a sharper decline was observed for SBs, where the volume of NPLs in SBs as a percentage of the total volume of NPLs in the banking sector decreased from 17 per cent in Q4FY12 to 3 per cent in Q4FY23. Regrettably, the volume of NPLs in the PCBs as a percentage of the total NPLs in the banking sector increased from 31 per cent in Q4F12 to 47 per cent in Q4FY23. Such a high concentration of NPLs in the PCBs reveals that NPL is not only a problem affecting the SCBs. Furthermore, the increase in the share of NPLs in PCBs shows that the performance of the PCBs has worsened substantially over time.

Policymakers in Bangladesh have been ignoring the severity of high NPLs for far too long. Pertinent stakeholders have voiced consistent apprehensions regarding the persistent decline in banking performance and its potential ramifications for the sector’s long-term viability. The predominant reliance on banks within the country’s financial sector implies that any deterioration in the banking sector’s condition will inevitably negatively affect overall economic growth. Hence, it is imperative to address and rectify the aforementioned issues without further delay.

Reasons behind NPLs: Based on the review of the past literature and analysis of the developments in the banking sector, a conceptual framework explaining the reasons behind high NPLs in the banking sector was developed. Under this conceptual framework, the factors influencing NPLs were classified under four categories: (a) institutional; (b) regulatory; (c) legal; and (d) data and informational.

Factors driving NPLs under the institutional category included: (i) bank directors, CEOs and senior officials placed and controlled by the government; (ii) loans sanctioned on political grounds; (iii) rescheduling of loans despite the poor record of repayment; (iv) writing off loans to reduce tax burden and clean balance sheets; (v) weak internal control and compliance risk management of banks; and (vi) inability of some banks to comply with BASEL III requirements.

Factors driving NPLs under the regulatory category included: (i) dual regulation by the Financial Institutions Division and the Central Bank; (ii) lack of independence of the central bank; (iii) privileges given to defaulters by the central bank; (iv) bank licenses given arbitrarily to crony capitalists; (v) recapitalisation of banks by the government; and (vi) quasi-monopolistic power of a few bank oligarchs.

Factors driving NPLs under the legal category included: (i) amendments to the Banking Company Act to favour vested interests; (ii) weaknesses in the Financial Loan Court Act; (iii) loopholes in the Bankruptcy Act; (iv) lenient legal stance against wilful defaulters and corrupt bank officials; (v) insufficient number of judges dealing with loan cases; and (vi) delays in the judicial process and long backlog of cases.

Factors driving NPLs under the data and informational category included: (i) limited access to timely data; (ii) apprehensions regarding the quality of data; (iii) absence of disaggregated data; (iv) low reflection of the use of data in decision-making and policy measures; (v) lack of transparency about the use of data in decision-making process; and (vi) false information, forged documents and fake companies used for obtaining loans. Table-1 illustrates this conceptual framework of the nexus between governance and NPLs.

The shortfall in loan loss provisioning requirements: On a bank’s balance sheet, provisions are assets put aside to cover losses expected to occur in the future. As of Q4FY23, the required loan loss provisioning was Tk 1010.3 billion, whereas the actual loan loss provisioning maintained was only Tk 795.7 billion which is 78.8 per cent of the requirement. The rise in the required loan loss provisioning and the gap between the required loan loss provisioning and the actual provisioning are equally worrying.

Management of commercial banks: From 2008 to 2022, the average expenditure-income ratio was 0.81 in SCBs and 0.74 in PCBs. This reveals the poor management effectiveness of both SCBs and PCBs, even prior to the start of the pandemic. Regrettably, PCBs have maintained an expenditure-income ratio above 0.70 over the past 10 years, indicating that their management has been consistently poor.

The decline in liquidity of banks: Excess liquidity in the banking sector has declined from Tk 16.9 billion in October 2022 to BDT 158 billion in October 2023. Excess liquidity as a share of the total liquid assets of the banking sector declined from 41 per cent in October 2022 to 37 per cent in October 2023.

This fall in excess liquidity has been mainly driven by the liquidity crisis in five of ten Islamic Shariah-based PCBs, plagued by poor governance since the ownership change of the bank. Analysis of the data shows that the average excess liquidity as a share of total liquid assets in IBs from January 2011 to December 2016 was 39 per cent but fell to 26 per cent between March 2017 and October 2023 after the change of ownership of Islami Bank in January 2017. Before the ownership change of Islami Bank, IBs had excess liquidity of Tk 101.12 billion in December 2016. However, after the ownership change of Islami Bank, IBs suffered a liquidity shortfall of Tk 22.18 billion in January 2023. The reason behind such a large shortfall should be investigated by the central bank.

Increase in advance-deposit ratio: Banks are experiencing pressure on their liquidity positions. Since the cost of living has increased, many people are forced to use their savings to make ends meet. The advance-deposit ratio (ADR) has increased from 0.80 in September 2021 to 0.87 in September 2023.

Negative real interest rate on bank deposits: The real deposit rate, calculated as the weighted average of the monthly deposit rate of all scheduled banks adjusted with the point-to-point monthly consumer price index inflation, fell from -4.78 per cent in October 2022 to -5.41 per cent in October 2023. The negative real interest rate on bank deposits means that a depositor becomes a net loser by keeping money in the bank.

Recommendations: Pursuing a hasty solution to Bangladesh’s complex and challenging banking situation is unlikely to result in any positive outcome for the banking industry and the broader economy. There are apprehensions that the culture of deception, dishonesty and distrust fostered in the banking sector will cancerously spread to other sectors of the economy and further degrade the state of good governance in the economy. If immediate action is not taken to resolve the problems, the nation’s long-term progress will be limited by the banking sector, which has consistently shown itself to be a vulnerable sector of the economy. This section discussed some of the pressing issues of the banking sector based on the limited data available at the time of writing. If the banking sector is expected to play any constructive role in the economic recovery, its performance must be improved drastically. Based on the findings of this report, the following policy recommendations are put forward:

Commercial banks need to be strengthened

• Appointment of board members of banks should be depoliticised and based only on qualifications and experiences • Loans should be sanctioned based on the Central Bank’s “Guidelines on Internal Credit Risk Rating System for Banks” • Single borrower exposure limit for commercial banks should be strictly enforced • Repeated rescheduling and writing-offs of NPLs should be stopped permanently • Internal Control and Compliance Departments of commercial banks should be revitalised, and effective internal audits should be ensured • The Central Bank should appoint firm administrators to oversee the operation of troubled banks which cannot comply with BASEL III requirements

Central Bank should be empowered to act in the best interest of the depositors

• The autonomy of the Central Bank should be upheld in line with the Bangladesh Bank Amendment Bill 2003 • Recapitalisation of poorly governed commercial banks with public money should be stopped • An exit policy for troubled banks should be formulated by protecting depositors’ money in those banks • The need for new banks should be assessed pragmatically before issuing licenses for new banks • Acquisitions of commercial banks should be probed for anti-competitive practices • A single individual or group of individuals should not be allowed to obtain majority ownership of more than one commercial bank

A conducive legal and judicial environment should be created. The Banking Companies Act should be amended to reduce both the number of family members on the board of directors and the tenure of each director to enhance transparency and accountability.

Dr Fahmida Khatun, Executive Director, Centre of Policy Dialogue (CPD); Professor Mustafizur Rahman, Distinguished Fellow, CPD; Dr Khondaker Golam Moazzem, Research Director, CPD; Mr Towfiqul Islam Khan, Senior Research Fellow, CPD; Mr Muntaseer Kamal, Research Fellow, CPD; and Mr Syed Yusuf Saadat, Research Fellow, CPD. towfiq@cpd.org.bd ; muntaseer@cpd.org.bd.

[Research support is given by Mr Tamim Ahmed, Senior Research Associate; Ms Marium Binte Islam, Research Associate; Mr Mahrab Al Rahman, Programme Associate; Ms Anika Ferdous Richi, Programme Associate; Ms Zazeeba Waziha Saleh, Programme Associate; Mr Rushabun Nazrul Yaanamu, Research Intern; and Mr M M Fardeen Kabir, Surveyor, CPD.]