Originally posted in The Business Standard on 16 August 2021

An ‘occupation-based perspective’ has been increasingly essential to understand the ‘health-economy dual’ crisis and management of that crisis

It can be said that the transmission channel of adversity caused by covid pandemic in the Bangladesh economy is well-understood. At the same time, it is highly unclear what is the recovery channel from this ‘health-economy dual’ crisis.

The path to recovery gets more complex when resilience capacity gets exhausted due to the prolonged period of the crisis. This has been causing major damage to a large number of occupations. This happens owing to different levels of opportunities for employment and income, different levels of recovery of linkage industries and different spatial reasons.

A large section of these occupations are related to the tertiary sector, i.e. different service oriented occupations. In other words, the recovery of these occupations is largely dependent on the recovery of major primary and secondary sectors – agriculture and manufacturing.

In this backdrop, an ‘occupation-based perspective’ has been increasingly essential to understand the ‘health-economy dual’ crisis and management of that crisis. Such a perspective is different from the usual approach of perceiving the ongoing economic crisis where employment and income related challenges are perceived in generic forms – ‘unemployed’, ‘loss of jobs’, ‘poor’, ‘new poor’ and ‘marginalised’.

Under the occupation-based perspective, translating those ‘broader generic categories’ of destitute people into ‘occupation-based categories’ would help to better understand the occupational challenges and would help to better target public actions to facilitate the recovery process.

According to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), there are 602 different types of occupations within the country. These occupations are spread over three broad sectors – primary (agriculture), secondary (industry) and tertiary (services). The top 15 occupational categories include field crop and vegetable growers (15.8%), livestock and dairy producers (8.5%), poultry farming (3.1%), wearing apparels (3.9%), construction of residential building (3.13%), retail sales of grocery (2.0%), retail sale of food in specialized store (2.4%), passenger land transport (2.5%), non-mechanized road transport (2.7%), tailoring services (2.4%), shop keepers (9.15%), shop sales assistants (2.3%), car, taxi and van drivers (2.4%), crop farm laborers (5.4%) and hand & pedal vehicle drivers (2.0%).

These 15 categories of occupations comprise 67.7% of total people engaged in different occupations. During the time of crisis, these 15 categories of occupations are found to be well-linked with major sectors which helped them survive and recover. Besides, public policy responses have well attended to these occupations under different stimulus packages.The opposite side of the coin is – as many as 587 occupations are employing the remaining one-third of total working population and those are mostly unaddressed in public actions. A large part of these occupations did not come in public policy discussions. Among the 587 occupational categories, those which are linked with primary (agriculture) and secondary (manufacturing) sectors are assumed to recover quickly once the economy bounces back.

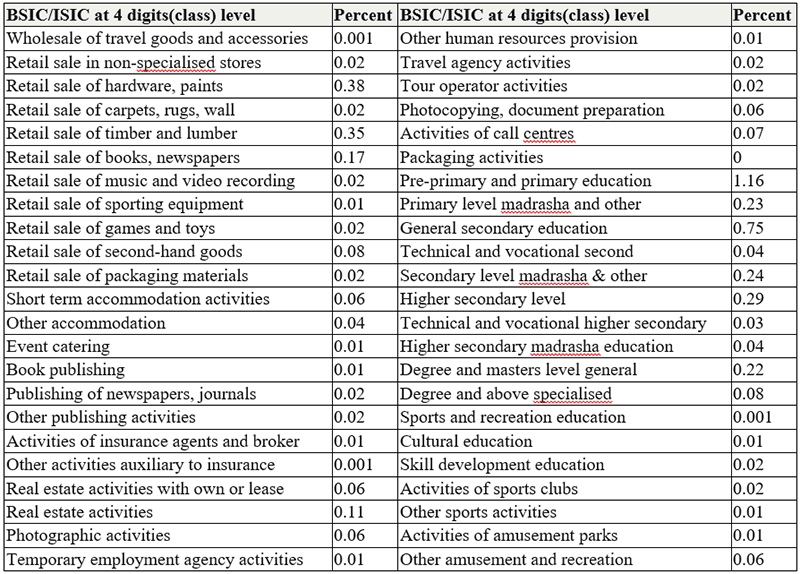

However, a large pool of people working in other occupations where linkages with overall economic activities is weak, are suffering and are likely to suffer in the coming days/years. Following table presents selected occupations which are less noticed and get less attention in public policy process

Table: Selected occupations which get less attention in public policy discussion and public actions, and share of their employment

All the above-mentioned occupations are related with different kinds of market and non-market tertiary activities. To note some, teachers in private education institutions like kindergartens, schools, colleges or madrasa, cultural professionals, sports professionals, animal vendors, printers and publishers, flower vendors, stationary proprietors, electronic vendors, seamstresses, etc. were some of the most affected professions.

Similarly, tourism business, hotels, traditional dine-in restaurants, cinema halls, barbershops, shopping complexes, book-sellers, show-piece shops, convention centres etc. were some of the most affected small and medium enterprises.

During the pandemic period, the majority of people working in these categories have been confronting dual challenges – difficulty in providing services due to health safety restrictions and lack of consumers’ demand due to uncertainty in normalcy in economic activities and pressure on individuals’ monthly earnings. Given the nature of activities where these people are involved, their recovery is highly conditional to the recovery of primary and secondary activities in agriculture, manufacturing and industries.

Thanks to limited opportunities and less public attention, a section of these people have been forced to take lower-graded jobs for survival. Overall, people of these occupations are on the verge of economic and social downgrading, which would cause a permanent loss of skilled professionals under these occupational categories.

Unfortunately, these people are largely untraced and unidentified and did not get attention in public discussion and policy actions. Majority of these people work in the informal sector and are less/unorganised and have no collective voice to raise their demands. Most importantly, these people have less political patronage both within the ruling party and the opposition. Hence, their voices are less-heard in the administration-driven public actions which are currently ongoing.

Public policy responses targeting different occupational categories are limited and sporadic. In July, 2021, the government has announced a stimulus package for transport workers, day labourers, small traders and water transport workers (Tk.450 crore).

Earlier it announced subsidised credit to farmers (Tk.5,000 crore), credit support for returnee migrants (Tk.900 crore) and credit support for fish farmers/shrimp farmers (Tk.100 crore). Besides, credit support provided to SMEs (Tk.23,000 crore), cash and kind support extended to the poor people, OMS operation and emergency food support through district commissioner’s office and local government offices – partially contributed to people in different occupations.

However, those support covers mainly the large occupational groups. Different occupational categories who are the worst victims of pandemic, are largely outside those supports.

Hence, the government needs a targeted support programme for people of those occupational categories who are the worst victims of pandemic and are still deprived of attention. Since the people in these occupations are less in number, the total amount of support required for them would not be so high.

However, these people may need support for more than once in a year till they get sufficient response from consumers for their services. It is expected that the people of those occupational categories will be quickly identified, will be included in the national database under social safety nets and will be provided support to help them survive and gradually recover. Moreover, the services which these occupations provide to the economy need to be attended both by the private sector and the public sector through targeted measures.

Dr Khondaker Golam Moazzem is the Research Director at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD)