Published in The Daily Star on Monday, 19 February 2018

Informal sectors need incentive to be formal

Analysts say at discussion

Star Business Report

Small enterprises need incentives and policy support to become formal as the graduation entails costs and lots of barriers, experts said yesterday.

Small enterprises need incentives and policy support to become formal as the graduation entails costs and lots of barriers, experts said yesterday.

They came up with the suggestion as they found that despite Bangladesh’s positive economic development for more than a decade, employment in the informal or unorganised sector has been increasing constantly.

“There are costs and barriers to formalisation,” said Mustafizur Rahman, a distinguished fellow of the Centre for Policy Dialogue, at an event held at the Westin Dhaka.

Adam Smith International, The Asia Foundation and the UK government’s Department for International Development jointly organised the event as part of its annual dissemination work on economic dialogue on green growth and inclusive growth.

Incentives should be there to bring the informal enterprises into formal ones, Rahman said.

He, however, said it will not be easy to bring the informal sector under the formal umbrella.

Rahman, who presented a paper on the informal labour market in Bangladesh at the event, also called for vocational education instead of relying on the traditional secondary education system to meet the needs of the future formal economy.

“We will have to deploy policies accordingly,” he said.

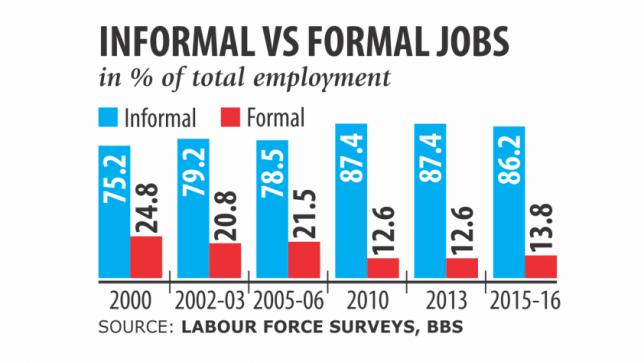

According to the Labour Force Survey (LFS) 2015-16, Bangladesh’s 86.2 percent labour force is engaged in some type of informal employment, up from 75.2 percent in 2000. Informal employment in the garment sector has also increased to 95.3 percent in 2015-16 from 92 percent in 2010.

But the definition of informal-formal dichotomy has undergone a number of changes in successive LFSs.

For example, before 2010, informality was associated with four attributes: unpaid family workers, irregular paid workers, day labourer in agriculture and non-agriculture, and domestic workers.

In 2013, those not receiving pension and not contributing to retirement fund were also added in the definition of informality. Debapriya Bhattacharya, a distinguished fellow of the CPD who moderated the programme, said an understanding of the informal sector is very important as lots of people are there.

Bangladesh’s economy has been going through structural transformation as it is moving slowly from agriculture to manufacturing.

Like other developing countries, Bangladesh’s services sector, which contributes to more than 50 percent of the gross domestic product, has been expanding, bypassing the manufacturing sector. “Services sectors absorb most of the informal employment.”

“If you remain informal, you remain outside of the government policy and incentives,” Bhattacharya said, referring his research in the 1980s, when small enterprises in old Dhaka’s Dholaikhal could not get financing from Agrani Bank because they did not have any formal documents, even trade licences.

Ismail Hossain, chairman of the department of economics of North South University, stressed on linking other policies, such as social safety nets and education with the informal and formal sectors.

He also called for skills improvement as low-skill entrepreneurs cannot get finance from banks.

Formality is now a label and firms tend to be formal because it is related to the productivity of the labour force, said Alberto Lemma, research fellow of the International Development Group.

“You have to be formal if you want to hire higher skill manpower.”