Originally posted in The Daily Star on 18 February 2025

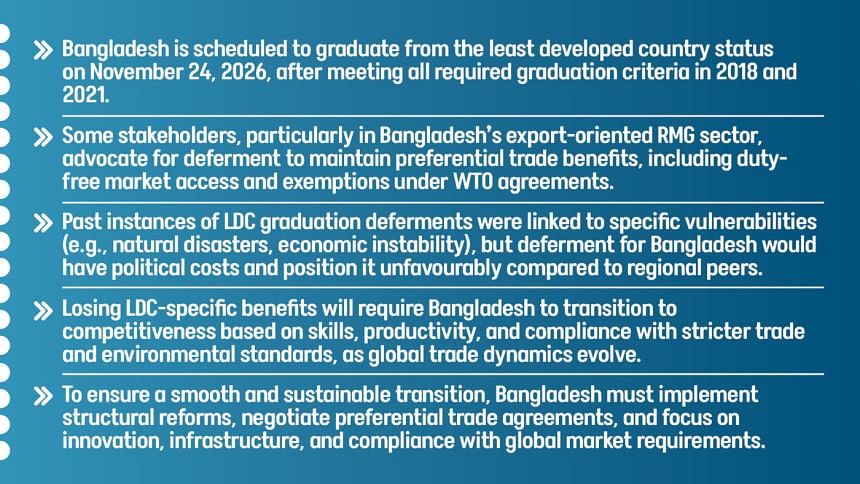

The title of this write-up may appear somewhat misleading, but there are valid reasons to pose such a question, as there is context to it. Bangladesh is set to graduate from the group of least developed countries (LDCs) on November 24, 2026. However, there are some sections among concerned stakeholders in Bangladesh who are arguing for the deferment of this graduation for an unspecified period. An objective analysis of the issue and an assessment of the veracity of the divergent views regarding it have practical significance.

As may be recalled, the group of LDCs was first identified by the United Nations in 1971 as a sub-stratum among developing countries. At the time, the global community felt that several developing countries would require special and additional international support measures (ISMs) to help them in their quest for economic development. Accordingly, a separate group of developing countries, called the LDCs, was identified for additional assistance and special and differential (S&D) treatment. What is important to note in this context is that inclusion in the LDC group was to be decided on the basis of certain criteria, but the decision for inclusion would only be effective if the concerned developing country agreed to be categorised as an LDC. On the other hand, graduation from the group would be decided based on the LDCs meeting the criteria stipulated for graduating out of the LDC group. In this sense, inclusion in the LDC group was voluntary, while graduation would be mandatory.

Accordingly, a developing country that satisfies the relevant criteria for inclusion in the LDC group may choose whether or not to join the LDC group. For example, in 2006, Zimbabwe rejected the determination by the UN Committee for Development Policy (CDP) to be categorised as an LDC (Bangladesh joined the LDC group in December 1975). Zimbabwe took this stance, stating that it “refuses to be downgraded as an LDC.” On the other hand, as noted, there is a defined procedure for an LDC’s graduation from the group. An LDC needs to meet the criteria for graduation and sustain the record over two successive triennial reviews carried out by the CDP. The CDP then recommends the LDC in question to the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) for graduation. Based on these, and following consultations and deliberations, the UN General Assembly (UNGA) takes the final decision regarding the graduation of the concerned LDC, as well as when the decision will come into effect.

The criteria for inclusion and graduation are periodically reviewed by the CDP; indeed, these have undergone several changes since 1971. According to the current procedures (2024), an LDC needs to meet at least two of the three graduation criteria to be considered for graduation: a GNI per capita of $1,306 and above, a Human Asset Index (HAI) of 66 and above, and an Economic Vulnerability Index (EVI) of 32 and below. An LDC may also be eligible for graduation based on the income criterion alone if its GNI per capita is three times the income graduation threshold (i.e. $3,918 or above) over two consecutive triennial reviews by the CDP.

To recall, Bangladesh first met the criteria for graduation in 2018. In fact, the country met all three criteria (at the time, the threshold for GNI per capita was $1,222 and above, while HAI and EVI values remained the same at 66 and above, and 32 and below, respectively). This record was sustained at the next triennial review of the CDP, held in 2021 (Bangladesh’s GNI per capita was estimated to be $1,827, HAI was 75.4, and EVI was 27). Bangladesh, thus, was set to be recommended for graduation to the UNGA, and the graduation was expected to be effective from 2024. However, graduation for all LDCs eligible for graduation at the time (in 2021) was deferred by two years because of the adverse impacts of the Covid pandemic on the economies of these countries. In this context, Bangladesh’s LDC graduation was recommended by the UNGA, in its meeting held on November 24, 2021, to be effective from November 24, 2026 (instead of 2024, which would have been the general scenario).

IS DEFERMENT OF GRADUATION AN OPTION FOR BANGLADESH?

As noted at the outset, a number of stakeholders in Bangladesh are calling for the deferment of Bangladesh’s LDC graduation. However, as mentioned, when an LDC satisfies the graduation criteria and the attendant procedure, it is the UNGA that takes the final decision. This has already been the case for Bangladesh, with a concrete timeline now set. It is true that the graduation of LDCs has been deferred in the past even when eligibility for graduation has been met by the concerned LDCs.

Decisions regarding the graduation of several Pacific Island LDCs—e.g., Small Island Developing Countries (SIDS), such as Vanuatu, Kiribati—were deferred several times, as these were considered highly vulnerable to environmental challenges (they were eligible for graduation primarily based on the “income only” criterion). Samoa’s graduation timeline was deferred by three years when it was hit by a tsunami (it finally graduated in 2014). In 2005, the UNGA unanimously adopted a resolution to defer the Maldives’ smooth transition period, and the country graduated in 2011. Nepal, an LDC that first met the graduation criteria in 2015 (three years earlier than Bangladesh), was not recommended by the CDP at the 2018 triennial review due to the devastating earthquake in April 2015, which brought havoc to the country’s economy and people’s well-being. Nepal was recommended at the next triennial review in 2021. Nepal will, thus, graduate (three years later than originally envisaged, plus the Covid-related additional two years) at the same time as Bangladesh (on November 24, 2026, along with Lao PDR). In 2023, the UNGA decided to extend the graduation of the Solomon Islands until December 13, 2027. Angola was scheduled to graduate in February 2021, but the UNGA decided to defer its graduation to a later date due to the deterioration of its economy.

The call for Bangladesh’s graduation deferment is being spearheaded by the country’s export-oriented RMG sector. Since the sector accounts for about 85 percent of Bangladesh’s total exports, the implications of losing preferences for the sector, as well as the country, are understandable. Deferment of graduation would allow Bangladesh to continue enjoying various S&D treatments in the WTO for which it is currently eligible as an LDC (e.g., as part of the 25 S&D provisions in the WTO specifically targeted at the LDCs). These include preferential access to almost all markets for almost all products of exports (about 70 percent of the country’s exports enjoy duty-free, quota-free market access as part of the 40 or so LDC-GSP schemes maintained by its trading partners), derogation from obligations under the WTO-TRIPS (Trade-related Intellectual Property Rights) Agreement, aid for trade support, assistance from the Technology Bank for LDCs, flexibility with regard to many compliance requirements, and financial support for participation in various global fora, etc.

Bangladesh will need to strengthen the competitiveness of its exports and regional and global integration of the economy from a position of strength. Photo: Star

LDC preferential treatment allows Bangladesh’s apparel to enjoy significant preferential margins in almost all destination countries (except the US market, where the GSP scheme does not cover most apparel items). Preferential market access is particularly important for apparel since import duties on these items in all major export markets tend to be significantly high (e.g., in the markets of the EU, UK, Japan, and Canada, these duties range from 10-15 percent). Additionally, Bangladesh has benefitted significantly from the derogation from TRIPS compliance, as evidenced by the impressive performance of the country’s pharmaceutical sector, both in the domestic and external markets. Indeed, among the LDCs, Bangladesh has the distinction of being the country that has benefitted the most from LDC preferential treatment due to its higher supply-side capacities compared to most other LDCs. Not surprisingly, the country has also the most to lose in the absence of preferences. Indeed, estimates carried out by the WTO (2020) show that, of the potential losses arising from preference erosion (in terms of foregone export earnings) to be incurred by the 12 LDCs (that were eligible for graduation at the time), 90 percent would be on account of Bangladesh alone!

While it is conceivable that the government may, at some future point, decide to submit a request for the deferment of graduation, there must be strong supporting arguments favouring the request. The CDP will closely monitor and assess the smooth transition process. In the final analysis, the UN General Assembly will need to be convinced of the reasons and justification for such a request. Ultimately, this is a political decision that Bangladesh will need to weigh very carefully.

Indeed, as the White Paper Committee Report has noted, according to the most recent triennial review by the CDP (in February 2024), Bangladesh’s eligibility for graduation has been reconfirmed. Even after taking into account the hyperbole about the development track record promoted by the previous government of Sheikh Hasina, “there is hardly any plausible reason, as of now, for Bangladesh to request a deferment of the exit date from the group,” the White Paper states. Bangladesh still has some time to make up its mind and take a decision regarding whether to make such a request. To be true, Bangladesh is considered by other LDCs (and many other countries) to be an outlier among the LDCs, given the size of its economy and the surplus score with respect to the relevant correlates. Asking for deferment has political costs as well. As the White Paper cautions, such a call for deferment “is going to invite political backlash from expected quarters.” As is known, Nepal and Lao PDR are gearing up for graduation at full speed; the issue of deferment is not on their agendas. Bhutan, in the South Asia region, graduated in December 2023 (the country did not ask for any deferment). Bangladesh’s deferment would result in a situation where, in the South Asian region, it would be the only country along with war-ravaged Afghanistan remaining as an LDC beyond 2026. Not a scenario to look forward to.

STRATEGIES GOING FORWARD

The fact is that a date (November 26, 2026) has now been fixed by the UNGA for Bangladesh’s graduation. The smart thing for Bangladesh to do, in this context, is to undertake the necessary preparations for a smooth and sustainable graduation from the LDC group.

As is known, Bangladesh has already prepared a Smooth Graduation Strategy, with concrete recommendations provided by the seven sub-committees. The strategy is to be approved by the National Committee on Graduation. The White Paper states that “concerns remain regarding coordinated implementation of the strategy, including the challenge of institutional and policy leadership.” Such concerns must be addressed through energetic actions and urgent initiatives in a time-bound manner. It will be prudent for Bangladesh to prepare for graduation in 2026 by undertaking the necessary reforms and ensuring structural transformation towards smooth and sustainable graduation. Trade policies, incentives, and import duties will need to be scrutinised to ensure compliance with global obligations that graduation will entail. There must be a transition from preference-based competitiveness to skills- and productivity-based competitiveness as part of the sustainable graduation strategy. Adequate measures will need to be taken to ensure compliance with TRIPS obligations, obligations under the Trade Facilitation Agreement, and other WTO-mandated Agreements (as are applicable for non-LDC developing country members of the WTO). Compliance with ILO Conventions and Protocols will need to be ensured and enforced.

As may be recalled, the EU and the UK (along with a number of other preference-providing countries such as Canada) have agreed to extend preferential treatment (duty-free market access) for goods originating from graduating LDCs such as Bangladesh for an additional three years following their respective graduation timelines. However, one must keep in mind that these are time-bound offers (and not all currently preference-providing countries have made this offer). Bangladesh’s work on preparing for graduation must begin earnestly, and now.

It is also to be recognised that the global trade and competitiveness scenario is set to undergo significant changes in the coming years, which will accentuate the graduation challenges for Bangladesh. Even if preferential market access under the EU’s GSP plus scheme remains an option for Bangladesh, after the additional three-year period ends, it must be kept in mind that under this scheme, the rules of origin will become more stringent (for example, in the case of RMG, this will require a two-stage conversion—yarn to fabric to RMG—instead of the current one-stage conversion from fabric to RMG). Moreover, the GSP plus scheme covers only 66 percent of the items imported by the EU. It is also important to note that, due to the threshold for GSP plus eligibility (the share of a single country in total EU-GSP imports of a particular item, as proposed under the new EU-GSP scheme to be effective from 2027), Bangladesh’s apparel items, its major export to the EU, will no longer be eligible for preferential treatment under the proposed stipulations. Negotiating with the EU (before the new EU-GSP scheme becomes effective in 2027) to raise the threshold should be seen as a high priority for Bangladesh’s policymakers.

Also, as shown by the outcomes of the 13th WTO Ministerial Conference in Abu Dhabi (held between February 26 and March 2 of last year), the proposal submitted by the LDC group in the WTO seeking a new set of ISMs for graduating LDCs failed to gain tangible traction among member countries.

There is a need to closely monitor how Bangladesh’s macroeconomic scenario develops and how the various indicators (criteria) associated with eligibility for LDC graduation evolve over the coming months. In the meantime, work on sustainable graduation must be carried out proactively and vigorously.

Bangladesh will need to strengthen the competitiveness of its exports and regional and global integration of the economy from a position of strength. Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreements (CEPAs) must be negotiated, and offensive and defensive strategies designed accordingly. In the absence of such trading partnerships and groupings, Bangladesh may end up needing to export on a non-preferential (i.e., most-favoured nation, MFN) basis, while its competitors, such as India, Pakistan, Vietnam, China, and Cambodia, enjoy preferential access in many markets (thanks to bilateral and regional free trade agreements and CEPAs of which these countries are members).

The global trading scenario is changing rapidly: there is an increasing emphasis on greening trade and trade facilitation, and compliance requirements for both preferential and non-preferential trade are becoming more stringent. Carbon dioxide emissions in the production process and supply chains are being tracked, and environmental, gender, and social considerations are coming into sharper focus. Ensuring compliance with these will require skill-based interventions, innovation in green technology, and training. To be sure, all these steps would require additional investment in infrastructure, technology, and capacity.

It is a matter of concern, though, that many graduating LDCs are still having to deal with the adverse impacts of Covid and the Russia-Ukraine war on their economies. Their domestic resource mobilisation continues to remain weak, and the level of inflation remains very high. It also needs to be kept in mind that many of the ISMs in favour of the LDCs, including the WTO-Hong Kong Ministerial Decision regarding DF-QF market access for goods and the WTO-Bali Ministerial Decision concerning the offer of preferential market access for LDCs in the services markets of developed countries, have not been implemented and operationalised. The promised significantly higher aid for trade and aid for trade facilitation have yet to be delivered. The emerging global and regional geo-economics and geopolitics are not conducive to the smooth graduation of the LDCs—making the smooth and sustainable graduation of currently graduating LDCs doubly challenging.

Renewed efforts will need to be undertaken, in partnership with other LDCs in the WTO, for the adoption of a new set of ISMs for the graduating LDCs in view of the next WTO Ministerial Conference (MC14), to be held in Cameroon from March 26-29, 2026. Pressure should also be put on the development partners to take concrete steps to implement the decadal Doha Programme of Actions for the LDCs (2022-2031) adopted in Doha in March 2022 at the LDC V Conference. It also needs to be emphasised that the WTO should align its decision with the spirit of the SDGs (particularly SDG 17), which calls upon multilateral agencies and various global platforms, such as the WTO, to take concrete steps in support of the LDCs. However, the emphasis ought to be on undertaking our own homework.

CONCLUSION

The upshot of the above discussion is that Bangladesh’s actions and priorities must focus on domestic preparatory measures and the implementation of the smooth and sustainable graduation strategy. Reforms and structural changes must be put in place, the capacity to access regional and global markets from a position of strength must be enhanced, and compliance with the newly emerging global trading regime must be ensured. Bangladesh’s efforts must be geared toward the new and next lap of its journey as a non-LDC developing country.