Originally posted in The Financial Express on 26 June 2024

On February 1, 2024, India’s Ministry of Culture announced that the West Bengal State Handloom Weavers Co-Operative Society secured the GI status for Tangail Saree under the name of ‘Tangail Saree of Bengal’, This move triggered outrage and criticism from a large cross-section of Bangladeshi citizens. On February 10, 2024, we presented at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) a detailed analysis of the issue titled ‘On Tangail Saree-GI by India: What Happened and What Can be Done?’ Later, the Prime Minister took note of the issue during a cabinet meeting held on February 11, 2024, and provided guidance for all relevant authorities to undertake necessary measures for the GI registration of the nation’s relevant products.

On February 1, 2024, India’s Ministry of Culture announced that the West Bengal State Handloom Weavers Co-Operative Society secured the GI status for Tangail Saree under the name of ‘Tangail Saree of Bengal’, This move triggered outrage and criticism from a large cross-section of Bangladeshi citizens. On February 10, 2024, we presented at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) a detailed analysis of the issue titled ‘On Tangail Saree-GI by India: What Happened and What Can be Done?’ Later, the Prime Minister took note of the issue during a cabinet meeting held on February 11, 2024, and provided guidance for all relevant authorities to undertake necessary measures for the GI registration of the nation’s relevant products.

The concerned government authorities announced different measures to secure the GI for the Tangail Saree on behalf of Bangladesh. Amidst the visible discontent among people, the Ministry of Industries called an urgent meeting on February 5, 2024, to discuss the processing of the GI application for Tangail Saree. On April 25, 2024, the GI certificate for Tangail Saree was issued in Bangladesh. Subsequently, on March 13, 2024, DPDT called for a meeting to resolve the matter of Tangail Saree GI by India and a Task Force was formed. CPD is a member of this Task Force or committee. On May 6, 2024, Neel Mason, an Indian-based lawyer and his associates were hired to consult on legal matters to protect the GI rights of Tangail saree of Bangladesh. Another meeting was held on June 9, 2024, to assess the steps undertaken and progress achieved by Mason and Associates. As was disclosed in this meeting, a first draft has been prepared to contest the Tangail Saree GI by India and the legal team has continued its effort to gather further evidence to strengthen their case.

As the backlash from the controversy over the Geographic Indications (GI) awarded to India for Tangail Saree begins to simmer down, a new concern has emerged. At the recently held Diplomatic Conference on Genetic Resources and Associated Traditional Knowledge organised by The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) in Geneva

(May 13-17, 2024), ‘Sundarban Honey’ was displayed as a GI product of India.

This information came to light through a tweet by the West Bengal Forest Department on May 16, 2024, declaring that ‘Sundarban Honey is the only GI product from West Bengal selected for Display’ at the Conference. This sole representation of the said product by India sparked questions in our minds as the majority of Sundarbans’s territory lies within Bangladesh. Bangladesh is the primary extractor of Sundarban Honey. While official government records could not be found, about 200-300 tonnes of Sundarban Honey are extracted annually, according to various media reports. India produces about 111 tonnes per year as mentioned in its GI application, as per the Geographical Indications Registry, Intellectual Property India.

Observed developments in Bangladesh and India regarding the Sundarban Honey GI registration: Bangladesh government’s Department of Patent, Designs and Trademark (DPDT) under the Ministry of Industries, on its website, has listed thirty-one GI products of Bangladesh as of April 30, 2024. This list does not include the Sundarban Honey. Curiously, the district administration of Bagerhat filed an application for the GI tag of Sundarban Honey six years back on August 7, 2017, and there has been no development since then! This is a rather astonishing example of administrative dereliction of duty. Thus, the GI of Sundarban Honey in Bangladesh has remained unsecured.

In contrast, West Bengal Forest Development Corporation Limited applied for GI rights for Sundarban Honey on July 12, 2021, and the GI tag was issued on January 2, 2024.

Transborder GI: A trans-border GI ‘originates from a geographical area which extends over the territory of two adjacent Contracting Parties’. In alignment with Articles 22-24, Part II, Section 3, of Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), each WTO member has an international obligation to ensure that a GI product genuinely originates from their territory. If there is confusion about the geographical origin, the concerned members should seek a mutually agreed upon solution. As per WIPO, when geographical indications are assigned to ‘homonymous products’ or shared resources, honest use of GI can be possible across countries provided that ‘the indications designate the true geographical origin of the products on which they are used.’

It is worth noting that in some instances, India did not specify the place of origin in the GI title (e.g. ‘Nakshi Kantha’), while in others, the designated geographical origin mentioned in the GI title did not fall within India’s demarcation (e.g. Tangail Saree of Bengal).

The Global Experience: Trans-border GI conflicts are not necessarily common, but they have occurred around the world. Issues arise when producers from different countries claim GI protection for similar products with overlapping geographical areas or historical connections. Let us recall some instances from global experiences.

Hungary & Slovakia- Tokaj wine. Hungary and Slovakia have been fighting over who can call their wine ‘Tokaj’ for years. An agreement reached through negotiation between the two countries in 2004 allowed some Slovak wine to use the name ‘Tokaj’, but Slovakia did not follow the agreed standards enshrined in Hungarian wine laws. While Hungary tried to stop Slovakia from registering ‘Tokaj’ in an EU database, courts sided with Slovakia, meaning both countries can use the name under EU law.

Chile & Peru- Pisco brandy. In 2002, Chile secured protection for its Pisco in the EU through a bilateral agreement. In 2005, Peru joined the Lisbon Agreement and accomplished international GI registration for Pisco. Consequently, the EU member states were obligated to protect both the Chilean and Peruvian Pisco GIs. The EU resolved this conflict by designating a Protected Geographical Indications (PGI) to Peruvian Pisco, Chilean Pisco was granted a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO), allowing it to use the name Pisco for its brandy. While some countries recognise both Chile and Peru’s claim to Pisco

(e.g. United States, Canada, China, and the European Union), others support Chile’s exclusive right to the appellation (e.g. Japan, Australia, New Zealand and Mexico). India, along with Nicaragua, Cuba, Panama, Venezuela, and Columbia supported Peru’s claim to the name. This ongoing dispute has resulted in significant costs for both countries as they have to engage in legal battles in every market a Pisco brand attempts to enter. This prolonged conflict shows the need for mutual recognition, which would help Pisco compete with other liquors globally.

Towards a Shared GI Covenant & LEGAL FRAMEWORK: One can safely say that these are not the last incidents between Bangladesh and India. Shouldn’t Bangladesh be looking for a predictable legal solution to the issue of shared geographical resources? Given the contingency of geographical proximity and shared natural resources, it is now obvious that we need to find a mechanism to have shared GIs as global members have for this purpose. In the subsequent part, we attempt to explore those options.

Without any established legal framework, tensions may continue to rise between Bangladesh and India regarding trans-border GI protection. The motive behind seeking such protection is entirely rational from a national perspective. Given the reputation and consumer faith that a GI status brings, it is in the economic interest of every country to register as many GIs as possible for their traditional products, regardless of the ambiguity of the exact geographical linkage. However, registering separately under the Sui Generis System of WIPO may make the GI product semi-generic in other countries. This may undermine the ability to command premium export prices as neither country can establish exclusivity over the product (as seen with Basmati rice) and may even result in a loss of protection against imitation. Furthermore, there will be apprehension about legal disputes if either country attempts to deter the other from entering international markets.

National Legal Framework

The prerequisite for any country to protect its origin-based traditional products is to register them first in the country of origin. Currently, 26 products from Bangladesh are in the pipeline and undergoing the process of receiving a GI certificate. Bangladesh needs to prepare a complete and adequate list of GI products identifying those that have explicit export potential, particularly focusing on shared GI items with India.

Global Legal Framework

The issue of trans-border GI protection is a novel area in the multilateral sphere and more attention should be paid to this issue in WIPO and the World Trade Organization (WTO). International protection of trans-border shared resources can be ensured by registering a GI under the following legal frameworks: (a) Bilateral agreements including with India; (b) The European Union’s (EU) system of intellectual property rights; (C) The Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement on Appellations of Origin and Geographical Indications, 2015.

Bilateral agreements including with India

A bilateral agreement is concluded between two countries on the basis of reciprocity in order to increase the protection of the countries’ respective geographical indications. To protect a GI in a particular jurisdiction or country, one has to apply to the competent authority of that country or region e.g., in India.

The European Union’s (EU) system of intellectual property rights

Non-European product names can be registered as Geographical Indications (GIs) if their country of origin has a bilateral or regional agreement with the EU. These agreements include mutual protection, allowing non-EU countries to claim exclusive rights over their products. There is no information indicating that Bangladesh has signed or intends to sign such an agreement with the EU. Additionally, two countries, Bangladesh and India, can jointly apply for PGI status for their shared resources under the EU’s GI scheme. Darjeeling and Kangra Tea are the two PGIs of India that have been included in the EU register. Both India and Pakistan have separately published journals before the EU’s Council for the PGI right over Basmati rice. However, neither country, as of now, has been granted this right.

The Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement on Appellations of Origin and Geographical Indications, 2015

The act allows contracting parties to jointly apply for the registration of Appellations of Origin (Aos)/GIs originating from trans-border geographical areas through a common competent authority. Although only 44 countries have signed the act so far it is a significant first step for extending the supranational protection of GIs alongside the AOs. Since the EU has acceded to the Geneva Act, EU-registered PGIs and PDOs are also protected by other countries that have signed this agreement. Countries that are parties to the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, 1883 or members of the WIPO with compliant legislation can join the Geneva Act.

As members of the Paris Convention, both Bangladesh and India are eligible to join. However, neither Bangladesh nor India has acceded to the act yet.

What Can be Done: To protect trans-border GIs effectively across borders, Bangladesh and India need to adopt a collaborative approach instead of a competing one based on shared understanding and mutual consultations.

A joint bi-national approach for exploiting trans-border GIs would be the best commercial strategy to enhance the recognition and value of the shared resources of both countries in international markets. For this purpose, the following measures should be adopted

Join the EU Regional Agreement and the Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement, 2015. We recommend that Bangladesh sign a regional agreement with the EU if it hasn’t yet and accede to the Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement 2015.

Explore potential avenues for joint protection of shared GI with India. Once both Bangladesh and India sign up for The Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement 2015, discussions can be initiated on submitting joint applications under the Geneva Act for all trans-border GIs. Since the EU has joined the Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement, any third country that joins this agreement will have their Geographical Indications (GIs) protected throughout the EU under the Lisbon system.

Sign a shared GI protection agreement with India. Although we expected that the issue of transborder GIs would be discussed during Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s recent summit-level visit to India, it was not addressed. We hope that this matter will be taken into consideration, and all necessary groundwork will be thoroughly prepared at the Secretary or Minister level, allowing it to be effectively addressed at the next summit-level meeting between Bangladesh and India. During Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s visit to New Delhi for Modi’s swearing-in ceremony, she extended an invitation to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who may visit Bangladesh in the near future. If this visit takes place, the matter of signing a shared GI protection agreement should be taken up. Bangladesh needs to work toward that end.

Parting Thought: Indeed Intellectual Property (IP) related issues would gather huge importance for Bangladesh during its next stage of national development including LDC graduation, SDG Delivery and transition to HMIC. The utilisation of science, technology and innovation (STI) will be critical for fostering productivity growth-driven economic diversification. Robust protection of intellectual property rights (IPR) will be a mainstay of this process, particularly for accessing technology, protecting local entrepreneurs (such as freelancers), and attracting FDI.

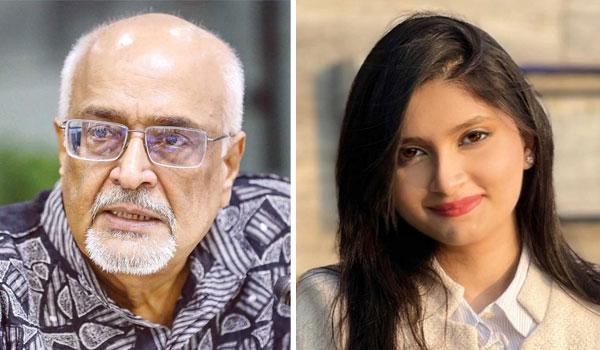

Dr Debapriya Bhattacharya is Former Ambassador of Bangladesh to WIPO, WTO and UN Offices in Geneva and Vienna; Member, United Nations Committee for Development Policies (UN-CDP); Convener, Citizen’s Platform for SDGs, Bangladesh; and Distinguished Fellow, Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), Dhaka. deb.bhattacharya@cpd.org.bd

[The piece is based on the presentation for the media by the author on Wednesday in Dhaka. Ms Naima Jahan Trisha, Programme Associate, CPD, has made important contribution in doing the background research.]