Originally posted in The Daily Star on 11 October 2025

Between dreams and debt

Excessive recruitment fees, low salaries, and permit costs trap thousands of Bangladeshi workers in Malaysia despite their vital remittances

- Migrants face debt, delays, deception daily

- Formal jobs offer stability and remittance

- Formal remittance channels gain migrant trust

- Bilateral reforms urged to curb exploitation

After paying Tk 5 lakh to a middleman, Ariful Islam finally made it to Malaysia a year ago. In the Southeast Asian country, it took him two more months to find a job at an Indian restaurant.

The work was far from ideal, but the 42-year-old was desperate to start sending money to his family in Brahmanbaria.

Now he earns about Tk 57,000 a month, including overtime.

From that, Islam manages to send home around Tk 34,000, though he has yet to start repaying the debt he took on to make the journey.

Living in a cramped shared room in Kuala Lumpur, the Bangladeshi worker has recently found himself worrying about how he will manage Tk 92,000 to renew his work permit.

“Middlemen at home promise immediate jobs, but the reality here is different,” he said.

His experience reflects that of many Bangladeshi expatriates in Malaysia who arrive full of hope and burdened with debt, only to face low pay, long hours and overcrowded accommodation.

Some, however, find more stable employment and manage to send sizable sums back home, a contrast that captures both the promise and the peril of migration.

BROKERS AND BILLS

From quiet Bangladeshi villages to Malaysia’s buzzing factories, construction sites and kitchens, hundreds of thousands have journeyed in search of better wages. Their remittances have helped keep Bangladesh’s economy afloat.

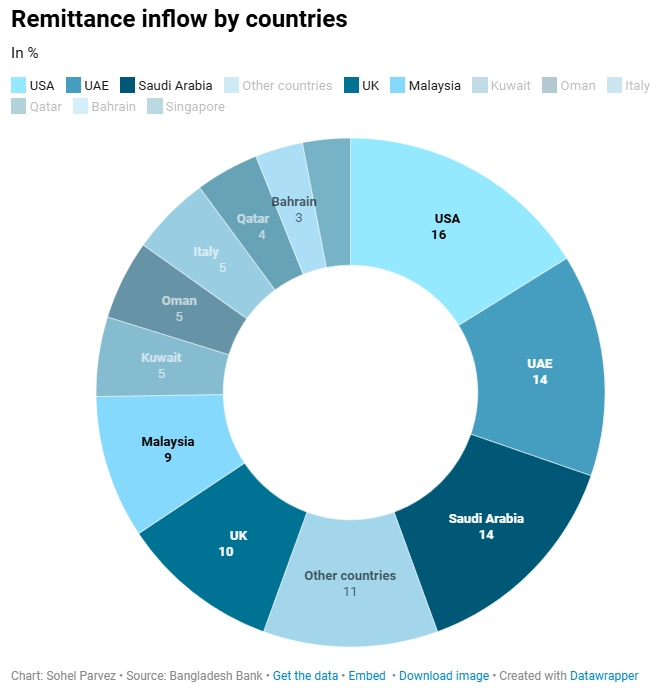

Meanwhile, Malaysia became the third-largest source of remittances for Bangladesh last year, contributing over $3 billion.

According to Bangladesh Bank data, Bangladeshi migrants sent a record $3.03 billion from Malaysia in 2024, accounting for 11.8 percent of total remittance inflows, up from $2.13 billion in 2022.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE remain the top two sources.

Most migrants now use formal banking channels, citing exchange rates that are nearly identical to those offered by informal and illegal routes such as hundi and hawla. Many also benefit from a 2.5 percent government incentive meant to discourage unofficial transfers. Yet the macro figures mask the precariousness of many workers’ lives.

The high cost of migration can turn opportunity into long-term indebtedness.

For instance, Mohammad Siam (32) from Cumilla paid Tk 3.6 lakh initially, but after political turmoil and delays, his total cost rose to Tk 5.7 lakh.

Delayed by visa issues, Siam was idle for six weeks before starting work.

Now, he sends Tk 45,000-Tk 50,000 monthly but says about 60 percent of migrants are in hardship.

“Those on free visas or deceived by middlemen suffer the most,” he commented.

Adding to the pressures, Mustafizur Rahman, distinguished fellow at local think tank Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), highlighted that many workers are trapped in a cycle of debt and low wages.

“High recruitment costs, low salaries, and annual work permit renewal fees, ranging from 2,500 to 3,200 ringgit, impose heavy burdens.”

Rahman said many workers resort to informal credit sources, paying interest rates of up to 10 percent monthly due to limited access to formal banking.

He criticised the poorly regulated recruitment chain, dominated by middlemen in both Bangladesh and Malaysia, and called for urgent reforms.

He also urged the government to pursue bilateral agreements to lower renewal costs and improve job security.

“Without systemic reforms, migrants will continue to face exploitation despite their vital contribution to the economy,” said Rahman.

Over the years, allegations of fraudulent recruitment and corruption have repeatedly disrupted labour flows to Malaysia.

The Southeast Asian country suspended recruitment from Bangladesh on May 31, 2024, amid reports of excessive recruitment costs, an oversupply of workers and the role of a syndicate of 101 agencies selected by the Malaysian government in 2022.

Similar actions were taken under earlier Malaysian governments, including a suspension in 2018.

A March 2024 letter from two UN Special Rapporteurs noted that Bangladeshi nationals were being charged between $4,500 and $6,000 in recruitment fees, far above the bilateral MoU of $720.

That makes Bangladeshi migrants among the most expensive to recruit globally, and it underlines how multilayered middlemen networks extract large sums from workers.

Researchers and industry insiders worry whether, when recruitment resumes, it will be open to all licensed agencies or again limited to a group of recruiting agencies. A Verité study published in May last year found that 96 percent of Bangladeshi migrant workers in Malaysia face exploitation risks tied to recruitment debt.

NOT ALL STORIES END IN DESPAIR

There are, however, examples of better outcomes under formal channels.

Md Aiub Ali (28) from Kalihati in Tangail paid Tk 4.5 lakh to go to Malaysia seven years ago and found employment with a Chinese firm producing steel water tanks.

Starting at Tk 52,000, his monthly earnings, including overtime, have since risen to about Tk 86,632.

After Tk 20,000 in expenses, he remits Tk 57,000-Tk 63,000 a month and prefers formal remittances for safety and parity of rates.

Monirul Islam (28) from Faridpur Sadar went to Malaysia two years ago and secured a job immediately at a government-owned cable company, earning between Tk 63,000 and Tk 75,000.

He spends around Tk 17,000 on living costs and remits the rest. These cases illustrate how transparent, formal recruitment and employment reduce uncertainty and exploitation.

THE NEED FOR THE RIGHT POLICIES

Bangladesh’s Deputy High Commissioner in Malaysia, Mosammat Shahanara Monica, acknowledged both progress and ongoing challenges.

“High migration costs, fraudulent practices, and labour exploitation remain serious issues,” she told The Daily Star, noting efforts to expand safe migration campaigns, outreach programmes and consular services.

Bangladesh now supplies nearly 40 percent of Malaysia’s foreign workforce, about 800,000 officially employed, with unofficial estimates closer to 1.5 million. Most work in construction, manufacturing and food services, earning between Tk 43,000 and Tk 115,510 a month. The average migration cost of Tk 4.5-Tk 6 lakh leaves many indebted for years.

Government-level initiatives include G2G labour agreements, periodic Joint Working Group meetings and active involvement of the Ministry of Expatriates’ Welfare and Overseas Employment to streamline processes.

Pranab Kumar Ghosh, first secretary (commercial) at the High Commission, credited policies discouraging hundi for rising formal remittance inflows.

He said remittance inflows have risen largely due to government policies aimed at curbing the use of unofficial channels.

Bangladesh Bank spokesperson Arief Hossain Khan highlighted mobile financial services and incentives that have made official channels more attractive.

“The government is offering a 2.5 percent cash incentive to remitters to discourage the use of hundi and other unofficial channels. Migrants can also use mobile financial services for instant transfers.

“Besides, they now get almost the same exchange rate from banks as from the informal market,” Khan said.

“For this reason, more and more migrant workers are sending their remittances through official channels,” he added.

But critics warn that policy attention often concentrates on remittance volumes rather than migrant welfare.

Shakirul Islam, chairman of Ovibashi Karmi Unnayan Program, a community-based migrant organisation in Bangladesh, argued that many workers remain indebted and exposed to harsh conditions.

“No doubt, there are lots of workers earning enough, but a large portion of them are also indebted and face harsh conditions in Malaysia. Instead of improving their lives, they are pushed into poverty and debt,” he said, calling for sweeping reforms and stronger regulation of both licensed and unlicensed brokers.

He urged that labour wings abroad, particularly in receiving countries, be better staffed and better equipped to protect migrants.

Bangladeshi migrants are integral to Malaysia’s economy, from construction sites to kitchens and factories, and their remittances sustain families and national reserves back home. Yet the billions sent annually are only one measure of this relationship.

Behind them lie personal stories of endurance, sacrifice and, in many cases, unmet expectation.

The policy challenge is clear: protect workers through fair recruitment, stronger consular support and meaningful regulation so that migration can deliver on its promise rather than deepen precarity.