Published in The Telegraph on Sunday 23 February 2020

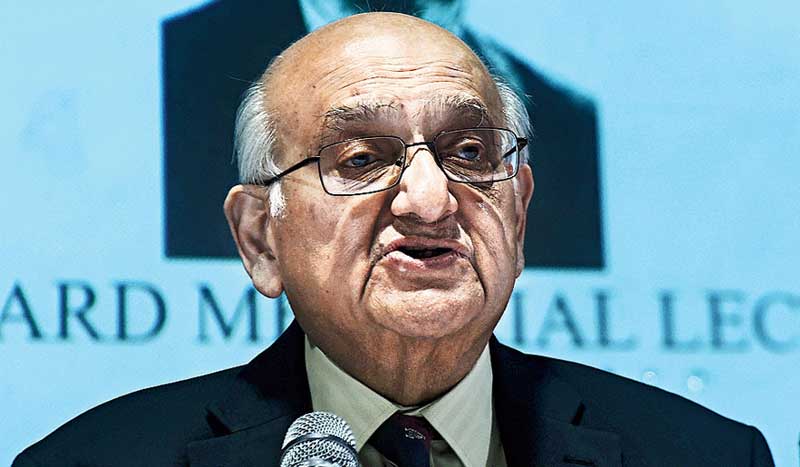

Rehman Sobhan was in the city to deliver the first Leslie James Goddard memorial lecture

Bangladeshi economist said on Saturday that the narrative that minorities in his country faced religious persecution was “not the real case” and “they are quite secure” in India’s eastern neighbour.

“I do not agree that the allegation that minorities are persecuted in Bangladesh is the case now. There is really no one persecuting them. In fact, under the present government of Sheikh Hasina, they are quite secure in Bangladesh,” said Rehman Sobhan, a senior fellow at Queen Elizabeth House, Oxford, and a visiting scholar at Columbia University.

Sobhan, who was born in Calcutta and studied in St Paul’s School, Darjeeling, was speaking on the sidelines of a lecture in the city on Saturday. He is also the chairman of Pratichi Trust (Bangladesh), set up by Nobel laureate Amartya Sen.

Sobhan was not commenting on developments in India, where attempts have been made to drum up support for the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) through a narrative that the minorities face religious persecution in neighbouring Bangladesh, Pakistan and Afghanistan, but was replying to a question from the newspaper on the allegation about the situation in his country. The CAA fast-tracks Indian citizenship to minorities from the three countries but not Muslims.

“The argument of minorities facing religious persecution is no longer relevant in today’s Bangladesh,” said Sobhan, who was in the city to deliver the first Leslie James Goddard memorial lecture. Goddard was a rector of St. Paul’s School, Darjeeling, and the Old Paulite Association had organised the lecture.

After the lecture, fielding questions from this newspaper, Sobhan, who was a member of the first Planning Commission in Bangladesh and a close associate of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, referred to his country’s economic growth rate to suggest that Bangladeshis do not migrate to India any longer.

As Bangladesh now has an average growth rate of 8 per cent — well above the Asian average — many economists think that there is no economic incentive for them to cross over to a country like India, which is projected to grow at only five per cent in 2019-20.

When Sobhan was told about the comment of Syed Muazzam Ali, former Bangladesh high commissioner to India, that Bangladeshis would prefer to swim the Mediterranean than come to India, the economist said he too felt that was true.

“Since Bangladesh’s economy has started to do very well people would not come to India for a better income. In fact there are a lot of Bangladeshis who are going to Europe,” Sobhan said. Most Bangladeshis arrive in India now while they are on transit, he added.

Sobhan, who was a professor at Dhaka University, said that Bangladesh had performed “really well” in human development indices, which measure the quality of life of the citizenry. “The country has done really well in health indicators like reducing child mortality, improving women’s health, done better in schooling children,” he said.

The garment industry in Bangladesh is the second largest in the world, second only to China, Sobhan pointed out. “Besides, we are also doing well in steel, pharmaceuticals, leather and boat building,” he added.

At the lecture, speaking about his days St Paul’s (1942-50), Sobhan, who was educated in Darjeeling, Lahore and Cambridge, remembered how the song that children sang changed over the years as India became independent. “When I was in junior school the students were singing God Save the Queen and by the time I left, the students were singing Jana Gana Mana,” he said.