Published in Dhaka Tribune on Tuesday, 14 March 2017

Just Faaland was the bridge between our newly-built nation and the rest of the world

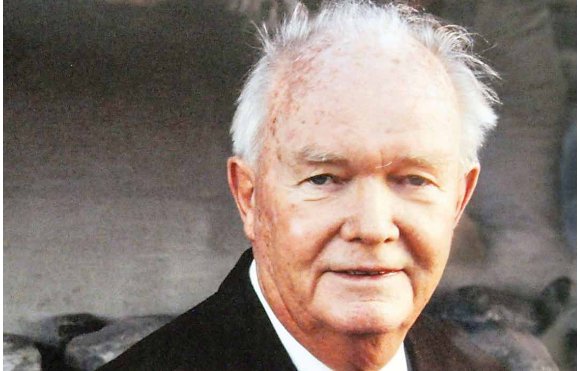

Just Faaland’s passing has deeply saddened his many friends in Bangladesh. Even in his 90s, he appeared to radiate an air of permanence, and could drive Rounaq Jahan and me back to our hotel in Bergen after entertaining us to a splendid tea prepared by his dear wife Judith at their home in Fantoft.

His mind was fully alert and he could reflect on past events involving his old friends with both insight as well as nostalgia.

Just Faaland enjoyed a special relationship with Bangladesh. In the first days of an independent Bangladesh, the World Bank extended a unique privilege to Bangladesh by inviting Professor Nurul Islam, the first Deputy Chairman of the recently set up Bangladesh Planning Commission, to suggest whom they should send out as their first country representative in Bangladesh.

Again, for the first time in their history, the bank offered us latitude to suggest someone who may not be on the regular staff of the Bank.

Nurul Islam, after consultation with Professor Mosharaff Hossain and myself, who were Members of the Planning Commission, then with the Prime Minister, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, and the Finance Minister, Tajuddin Ahmed, suggested to the World Bank that we invite Just Faaland to assume this position.

On the occasion of the first meeting of Bangladesh with its community of aid donors, Just played a particularly helpful role

Just was known to us from his tenure with the Harvard Advisory Group that advised the Pakistan Planning Commission in the 1960s and was already quite well informed about the Bangladesh economy.

He had returned from Pakistan to resume his directorship of DERAP, the development wing of CMI, which he built up as a reputed centre for development research.

But one of Just’s main attractions to us was his citizenship of a small country, Norway, presumed to have no hegemonic aspirations or interest in influencing the policy directions of an independent Bangladesh.

During his short tenure as the World Bank’s resident representative in Bangladesh, Just performed heroic services for the World Bank but also for Bangladesh.

He set up the World Bank office from scratch and established its presence as primus inter pares among the international community of aid donors to Bangladesh.

At the same time, he extended extraordinary respect to the fierce desire of a newly independent nation to protect its policymaking sovereignty from external donors, including the World Bank, seeking to influence our policy agendas. During these early days, he worked closely with the Planning Commission, building bridges for us with the international community, often arguing our case during potentially conflictual encounters with particular donors and advising us of forthcoming problems in relations with the Bank.

At the same time, he extended extraordinary respect to the fierce desire of a newly independent nation to protect its policymaking sovereignty from external donors, including the World Bank, seeking to influence our policy agendas. During these early days, he worked closely with the Planning Commission, building bridges for us with the international community, often arguing our case during potentially conflictual encounters with particular donors and advising us of forthcoming problems in relations with the Bank.

On the occasion of the first meeting of Bangladesh with its community of aid donors, Just played a particularly helpful role. The World Bank was anxious to recreate the consortium of Aid donors which it had led through the 1960s and used as a major instrument of policy influence over Pakistan.

The Planning Commission, with full political support from Bangabandhu and Tajuddin, firmly rejected the idea of recreating a Bank-led Consortium.

We indicated to the Bank that it would be only willing to meet collectively with our aid donors if the meeting was held in Dhaka rather than Paris where the Pakistan aid consortium traditionally met, and that the meeting should be hosted and coordinated by the Planning Commission, on behalf of the Government of Bangladesh.

The bank was persuaded to accept our assertion of sovereignty even though our resource position was far from robust, largely through Just Faaland’s persuasive argumentation on our behalf with the Bank’s leadership.

The Dhaka aid group meeting, which included countries which traditionally had not been included in World Bank led consortium, was convened in March 1973.

The event, organised by the Planning Commission at the then Intercontinental Hotel was deemed a great success and was well received by the donors who were impressed with the professionalism of our arrangements and preparation of documentation.

Through the meeting they were better able to recognise the unique problems of a war-devested, new country and appreciate what we were doing to address these problems, even if everyone there did not share our policy perspectives.

The World Bank, for the first and, as it transpired, the last time for many years to come, played a subordinate role in the event, even though their delegation was led by its Senior Vice President, Peter Cargill who had for years played the role of pro-consul, as the leader of the Aid Consortium, in influencing policy in Pakistan.

When Just departed from Dhaka, he demonstrated his deep emotional commitment to Bangladesh by taking back to Bergen a baby girl for adoption by his son

The World Bank was, however, not fully prepared to accept its more modest status in the affairs of Bangladesh.

Nurul Islam was advised by Just Faaland that the bank was active in persuading some of the leading aid donors such as the US, UK, and West Germany, to use the threat of withholding aid pledges if Bangladesh did not accept a share of the outstanding debt liabilities incurred in Pakistan in the 1960s to its aid donors which were now in default.

The Planning Commission had taken the view, following consultation with Bangabandhu, Tajuddin, and Kamal Hossain, who had just taken over as foreign minister, that we would, under no circumstances, accept such obligations until Pakistan would recognise our sovereignty and then come to an agreement over the division not just of our shared liabilities, but also our shared assets.

When Nurul Islam made our position clear to Peter Cargill, on the eve of the Consortium meeting, we were again alerted by Faaland, that Cargil, using the offices of a senior civil servant, intended to go over our heads to meet Bangabandhu and persuade him to be more reasonable and overrule his “hot-headed” academic colleagues in the Planning Commission.

Thanks to Faaland, Nurul Islam could alert Bangabandhu, Tajuddin, and Kamal Hossain about this forthcoming power play by the Bank. When Cargill was eventually given an interview on the evening before the Aid Group meeting concluded Bangabandhu informed him, in no uncertain terms, that notwithstanding Bangladesh’s exceeding difficult economic situation, we would not be pressured by our donors to compromise our sovereignty and fundamental negotiating positions with Pakistan over the issue of sharing debt liabilities.

As a consequence of this historic encounter, Cargill pressured the principal aid donors to threaten to withhold their aid pledges at the concluding session of the Aid Group meeting, to be held the next day, until we accepted a share of Pakistan’s debt obligations.

As a consequence of this historic encounter, Cargill pressured the principal aid donors to threaten to withhold their aid pledges at the concluding session of the Aid Group meeting, to be held the next day, until we accepted a share of Pakistan’s debt obligations.

We had again been briefed by Just Faaland of this forthcoming action, so that Nurul Islam, with the full authority of the prime minister, in one of our finest hours of self-assurance, could advise the Aid Group that their attempt to pressure Bangladesh was unacceptable and that their threat to withhold aid would be struck out from the proceedings of the Aid Group meeting.

Subsequent to this meeting, we went over the head of Peter Cargill and opened up communication with Robert McNamara, the president of the World Bank, again using the good offices of Just Faaland. Through this process, a compromise acceptable to Bangladesh was worked out whereby aid could resume.

Just Faaland’s advocacy on behalf of Bangladesh did not go unnoticed by the World Bank that subsequently terminated his tenure as their resident representative in Bangladesh. As far as I know, the Bank has never again invited an outsider to be its representative in any member country or given it the authority or say in identifying its representative there.

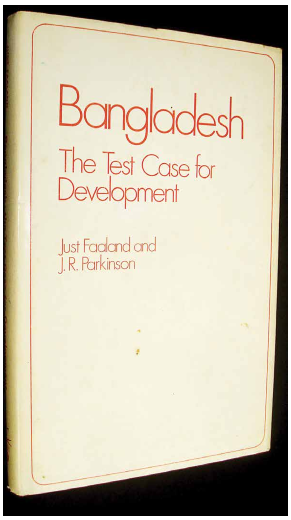

Nurul Islam, Just Faaland, and Jack Parkinson, who was a professor of Economics at Nottingham University and had served with Just in Dhaka, wrote an excellent and insightful book, Aid and Influence, on Bangladesh’s relations with its aid donors. Faaland and Parkinson had together also published an earlier work, Bangladesh: The Test Case for Development which drew on their experiences in Dhaka to identify, with insight and sympathy, the problems and prospects for Bangladesh.

This work is also something of a classic and source of reference among development historians.

Happily for Bangladesh, today we can claim to have passed the tests set for us by Faaland and Parkinson, with at least a B+ mark if not an A.

During his tenure at the World Bank in Dhaka, Just had built up strong interpersonal relations with Nurul Islam, Mosharaff Hossain, and myself which extended to our families, so when he departed Dhaka, he not only left behind an appreciative host government but a set of deep friendships which have lasted a lifetime.

This capacity to relate to people he worked with extended well beyond the Planning Commission and extended to every person he related to across Bangladesh.

This was part of Just’s unique style of work which built strong personal relations with those he worked with across the world.

When Just departed from Dhaka, he demonstrated his deep emotional commitment to Bangladesh by taking back to Bergen a baby girl for adoption by his son.

Just’s love affair with Bangladesh did not end with his return to CMI in Bergen.

I had left the Planning Commission in September 1974, about the time Just had left Bangladesh, and in the absence of Nurul Islam, I had taken over as chairman of the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS).

Writing from CMI, Just proposed to me that we should take advantage of his now deeper understanding of Bangladesh and close relations with its professional community by establishing an institutional link between BIDS and CMI. He suggested that we could do collaborative research, exchange scholars, and build up a body of knowledge and expertise on Bangladesh’s development at CMI.

Just invited me and Professor Mosharaff Hossain, who had preceded me as chair of BIDS, to visit Bergen in the summer of 1975, where we discussed the institutional and operational arrangements for this collaboration.

As chair of BIDS, I signed an historic agreement with Just Faaland which set in motion an agenda for collaboration which has kept CMI academically engaged with Bangladesh for the next 40 years.

Between 1975 and 1995, scholars from BIDS and CMI have moved back and forth to engage in research on Bangladesh.

Under this program, scholars from BIDS and other Bangladeshi scholars have been invited to spend extended time as visiting fellows at CMI where its outstanding research facilities, with its excellent collection of literature on Bangladesh accumulated over the years in its library, have provided opportunities for working on Bangladesh rarely available elsewhere.

I have myself benefitted on a number of occasions from these facilities. On one such occasion, Professor Muzaffar Ahmad and myself, spent two months as visiting fellows at CMI in the autumn of 1976 where, drawing on data we had brought in from our field research in Bangladesh, we worked long hours, undisturbed, to finish a 600 pages manuscript, on Public Enterprise in an Intermediate Regime.

When the BIDS-CMI agreement concluded, I had the opportunity to further perpetuate this relationship through a CMI partnership with Centre for Policy Dialogue, which I had set up in 1993, following my retirement from BIDS.

The CMI-CPD partnership continued from 2010-2015 and led to a further exchange of scholars and research collaboration which has yielded a rich harvest of important publications such as Professor Rounaq Jahan’s works “The Parliament of Bangladesh” and Political Parties in Bangladesh; and other writings by senior CPD colleagues. A number of valuable publications, prepared by CMI scholars have also come out of this project.

As an end product of its collaboration with BIDS and CPD, CMI has emerged as a repository of knowledge on the development of Bangladesh, where few institutions anywhere in Europe have been so well informed of a country which is not on their immediate radar screens.

In these long years of institutional collaboration, Just Faaland’s presence has served as a benign presiding spirit, providing leadership at all points

This body of knowledge has served Norway well and contributed to sustaining their excellent relations which have historically prevailed with Bangladesh.

In these long years of institutional collaboration, Just Faaland’s presence has served as a benign presiding spirit, providing leadership at all points, encouragement during lags in the encounter, and undiminished hospitality to all visiting scholars from Bangladesh.

For some of us such as myself, Nurul Islam, Mosharaff Hossain, and Kamal Hossain, Just and his wife Judith have become lifelong friends at the family level where we have invariably been welcomed into their home in Fantoft during our many visits to Bergen, where both the warmth of their hospitality and the excellence of Judith’s cuisine have sustained us through many convivial evenings.

Even when Just, retired as director of CMI, he retained a presence at its premises at Fantoft which always reassured us that nothing had changed in the continuity of our institutional and personal relations with CMI.

Just, even after his retirement, kept himself active, undertaking periodic influential assignments. This included leading several missions to Bangladesh, where he was involved with Rounaq Jahan, among others in evaluating a major project.

On another occasion, during the tenure of the Awami League government led by Sheikh Hasina between 1996-2001, Just led a team of experts to prepare a report for advising Motia Chowdhury, as minister for agriculture, on agricultural development strategy for Bangladesh.

He also maintained a long standing institutional relationship with Malaysia where he built relations of no less intimacy than with Bangladesh, which was recognised by their government through a state award to him of the highest rank.

His recognition in the international development community also remained of a high order. At one stage he served a term as head of the OECD Development Centre in Paris and also headed many international expert groups where his skills as both mediator and draftsmen of the final report attained legendary proportions.

I had some personal evidence of this when he chaired a high level advisory group on the LDCs convened by UNCTAD of which I was a member.

Only Just’s undiminished human skills averted a major breakdown in our enterprise due to sharp differences between myself and another member from an LDCs with a member of the group from the US. Happily, Just could take on the drafting of the final report which proved acceptable to both sides.

Just Faaland remained a legend in the world of development not just because of his significant professional skills, but because of his wide knowledge as well as experience of the developing world and his understanding of the importance of building strong inter-personal relations in the international arena. This invested him with the vision to look beyond national boundaries and proclaim himself as a genuine citizen of the world.

I do not believe I have encountered or will encounter too many people of his vision, humanity, and generosity of spirit. His loss to Judith, his lifelong companion and love of his life, and to his family is unbridgeable.

But they should feel comforted that this loss is shared not just across Norway, but around the world by so many who have had the good fortune to know him.

May his soul rest in peace and his memory inspire friendships across all borders.