Published in Dhaka Tribune on Monday 10 June 2019

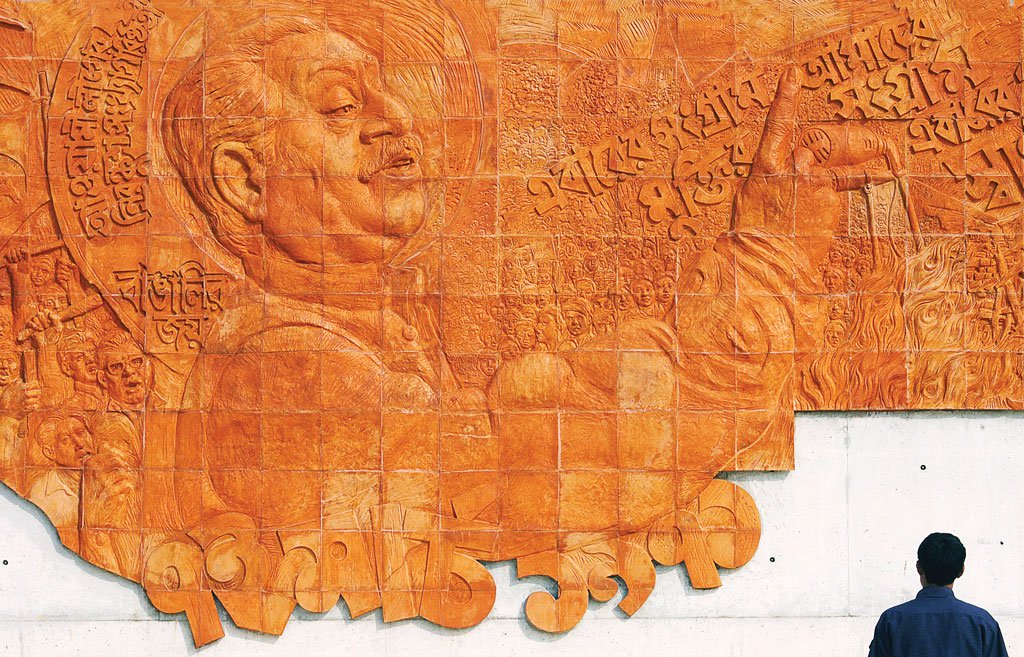

A leader who was always one with the people

For our generation who witnessed the birth of Bangladesh, it is a daunting task to express in words the unique role played by the Father of the Nation, Bangabandhu Shiekh Mujibur Rahman in the creation of the new state. It is even more challenging to analyze the political ideas underpinning his life’s work. Whenever I think of Bangabandhu I first remember those exciting and memorable days of March 1971.

I consider myself to be very lucky that I was able to witness the events of March 1971 and Bangabandhu’s role in creating history. Very few people are fortunate enough to see the making of history. I witnessed the transformation of our movement for autonomy into our struggle for independence. I witnessed how the main actor of this historic transformation, Bangabandhu Shiekh Mujibur Rahman, realized an impossible dream. There have been leaders in other countries who led their nations. But few could create history. Bangabandhu was one such rare grand actor of history.

It is unfortunate that even after 48 years of our independence and 43 years after his assassination there is no well-researched comprehensive biography of Bangabandhu Shiekh Mujibur Rahman. Fortunately two recent books, based on his personal diaries, have been published which can serve as original source that help us understand his ideals and political philosophy.

The first book, The Unfinished Memoirs, published in 2012, throws light on his childhood, and early political life. Though The Unfinished Memoirs does not include events after the late 1950s it still illuminates his political thoughts very clearly.

The second book, Karagarer Rojnamcha (prison diaries) which was published in 2017, is based on his diaries when he was in prison after he launched the six point movement in 1966. Here again his political thoughts are made very clear. He discusses at length the different methods of suppression of people’s movements pursued by an autocratic state. He highlights the importance of fundamental civil and political rights, particularly the need for ensuring freedom of expressions for sustaining democracy.

In this article I quote extensively from his writings so that we can hear his own voice. To understand his political philosophy we should always keep in mind that Bangabandhu spent most of his life as a political player outside state power. He struggled against colonial and undemocratic state power, first against the British and later against the Pakistan state to establish the economic, political, and cultural rights of the Bengalees.

He exercised state power only for a limited period of time — barely three and a half years after independence. His political discourse, as illustrated in these two books, is that of a leader fighting authoritarian state power, not that of a leader who was using state power to govern a country.

One of the remarkable features of his political life was his transformation from an ordinary rank and file worker of a political party to an unparalleled leader of millions of people. Bangabandhu possessed outstanding organizational capacity; at the same time he was a great orator. Generally we do not find such a combination of qualities in one leader.

In his Unfinished Memoirs Bangabandhu notes that he was more interested in party organizational work than in discussing theoretical and ideological issues. Though he was not a political theoretician, Bangabandhu had a few specific political ideals and goals and he worked consistently to achieve them. His values are best captured in three sentences which Bangabandhu penned on May 3, 1973. He writes:

“As a man, what concerns mankind concerns me. As a Bengalee, I am deeply involved in all that concerns Bengalees. This abiding involvement is born of and nourished by love, enduring love, which gives meaning to my politics and to my very being.”

The above quote makes it clear that Bangabandhu identified himself both as a human being and as a Bengalee.

This self-identification helps us explore the main features of his political philosophy, such as nationalism, secularism, socialism, and people-orientation.

Nationalism

Independence, liberation, and democracy

From the beginning of his political life, Bangabandhu was proud of his Bengali national identity. He was involved in the Pakistan movement but he believed that Pakistan should be established on the basis of the Lahore Resolution which envisaged two Muslim majority independent sovereign states.

He perceived the nationalist movement not simply as a struggle to gain independence from the rule of an external colonial power but also as a struggle for the economic and political emancipation of the down-trodden masses from various forms of oppression.

He joined the Pakistan movement in the hope that poor Muslim peasants will be liberated from the exploitation of the landlord classes. He had always viewed the Bengali nationalist movement as a movement for the achievement of democracy as well as liberation of the oppressed people. Thus on March 7, 1971 he called upon the people to launch simultaneously the struggle for independence and liberation.

Prior to the establishment of Pakistan, when as a student in Kolkata, Bangabandhu joined the Muslim League. He belonged to the Shaheed Suhrawardy and Abul Hashem faction of the party which was known as the progressives group. In his Unfinished Memoirs he writes:

“Under Mr Suhrawardy’s leadership we wanted to make the Muslim League the party of the people and make it represent middle-class Bengali aspirations. Upto that time Muslim League had not become an organization that was rooted in the people. It used to serve the interests of landlords, moneyed men, and Nawabs and Khan Bahadurs.”

After the creation of Pakistan, Bangabandhu returned to Dhaka and became involved in various progressive movements and organizations which championed the linguistic, cultural, and economic rights of the Bengalis. In 1948 he was imprisoned for participating in the movement demanding recognition of Bengali as one of the state languages of Pakistan.

He was also involved in other social and political protest movements, such as the movement of poor peasants against prohibiting inter-district trade in rice known as the “cordon” system. He supported the movement of the fourth class employees of Dhaka university and was again imprisoned in 1949.

Within a relatively short period after the establishment of Pakistan he became convinced about the need for establishing an opposition political party not only for championing the rights of the Bengalis but also to challenge the authoritarian rule of the Muslim League. In his Unfinished Memoirs he explained the rationale for the establishment of the Awami League in the following way:

“There is no point in pursuing the Muslim League any longer. This party has now become the establishment. They can no longer be called a party of the people … if we did not form an organization that could take on the role of the opposition the country would turn into a dictatorship.”

In 1949, the Awami Muslim League (AML) was founded and Bangabandhu was elected the joint secretary of the party though he was still in prison. In 1953 he became the general secretary of the party. The demand for self-rule gained increasing popular support in East Bengal from the mid-1950s. In 1955 Bangabandhu became a member of the Pakistan National Assembly (NA). In one of his speeches in the NA we already find a strong articulation of various demands of the Bengali nationalists and his strong sense of Bengali identity. He said:

“They want to place the word ‘East Pakistan’ instead of ‘East Bengal.’ We have demanded so many times that you should use Bengal instead of Pakistan. The word Bengal has a history, has a tradition of its own. You can change it only after people have been consulted. If you want to change it then we have to go back to Bengal and ask them whether they accept it … what about the state language Bengali? What about joint electorate? What about autonomy? … I appeal to my friends on that side to allow the people to give their verdict in any way, in the form of referendum or in the form of plebiscite.”

In the council session of the party in 1955 the Awami League (AL) dropped the word “Muslim” from its name and Bangabandhu again became the general secretary of the party. In February 1966, Bangabandhu presented his historic six points demand which put forward a very radical notion of provincial autonomy leaving only limited powers in the hands of the central government.

In March of that year he became the president of the AL and began a country-wide campaign to popularize the six points which soon became the sole agenda of the party. Six points captured the aspirations of the nation and it was billed as the charter for the liberation of the Bengalis. Following the launch of the six points, Bangabandhu was again imprisoned and he was charged with treason by the Pakistan government in the Agartala conspiracy case.

In 1969, Ayub fell from power in the face of massive students’ movement. Bangabandhu was released from prison and the students conferred on him the title of Bangabandhu (friend of Bengal). During the 1970 election campaign Bangabandhu started using nationalist slogans such as “Bangladesh” and “Joy Bangla.”

Thus, within a relatively short span of four years, between 1966 to 1970, Bangabandhu was able to unite the whole Bengali nation behind his demand for liberation and independence. I do not think any other nationalist leader had been so successful in mobilizing such a huge number of people within such a short period of time.

It is noteworthy that though throughout his life Bangabandhu was involved in movement politics and talked about people’s emancipation from exploitation and oppression, he believed in peaceful non-violent political movements. From 1947 till 1970 the Bengali nationalist movement became stronger day-by-day under his leadership but he stayed within the bounds of democratic politics.

Whenever Pakistani rulers gave opportunities for election he participated in them, though the elections were often not free and fair and attempts were made to foil the election results. In Karagarer Rojnamcha he points out repeatedly that by limiting the democratic space an autocratic regime ultimately leads the country towards terrorist politics. He writes:

“Newspapers arrived. I was alarmed that they [the Pakistani government] are trying to shut down democratic politics … If anybody criticizes the government there will be cases against them under the proposed secret act … I myself am facing five cases under article 124, section 7 (3) for making public speeches … My fear is they are leading Pakistan toward terrorist politics. We do not believe in that politics. But those of us who want to do good for the people through democratic politics, our space is shrinking.”

Secularism

Non-communalism and equal rights for all citizens

Though he was a Bengali nationalist, Bangabandhu never tried to create division and hatred between different identity groups. Many nationalist politicians use provocative languages and symbols that encourage violence between different groups. These days we are witnessing the rise of such nationalist leaders even in Western democratic countries who are trying to instigate intolerance and violence towards minority groups. But Bangabandhu’s nationalist politics was different. He believed in co-existence and mutual tolerance of different identity groups and talked about equal rights of all citizens. He always stood against communal violence.

Though he was involved in the Pakistan movement he believed that in India, Muslims and in Pakistan, Hindus should enjoy equal rights as citizens and live together in peace and harmony. He talked about equal rights of all groups to practice their respective religions.

He witnessed the communal riots in Kolkata on August 16, 1947. He points out that Suhrawardy asked his supporters to observe the day in a peaceful way so that no blame could fall on the Suhrawardy government. But unfortunately, communal riots did break out in Kolkata and later spread to Noakhali. Bangabandhu saved both Muslims and Hindus from acts of communal violence in Kolkata. Later when Suhrawardy joined Mahatma Gandhi in efforts to bring back communal harmony, Bangabandhu joined them.

After returning to Dhaka he joined Gonotantrik Jubo League and took up the cause of building communal harmony as his main mission. He was against all forms of communal violence, not simply between Hindus and Muslims but also between different Muslim sects and between Bengalis and non-Bengalis.

In his Unfinished Memoirs he strongly condemns the anti-Kadiyani riots that took place in Lahore in 1953. In 1954, when riots broke out between Bengali and non-Bengali workers in Adamjee jute mills in Narayanganj, he rushed to the area to calm the situation. In 1964 when Hindu-Muslim riots spread in India he started a civic campaign to prevent communal riots in East Bengal. Even in his March 7, 1971 speech he asked people to remain vigilant against the threat of communal violence. He said:

“Be very careful, keep in mind that the enemy has infiltrated our ranks to engage in the work of provocateurs. Whether Bengalee or non-Bengalee, Hindu or Muslim, all are our brothers and it is our responsibility to ensure their safety.”

In his personal life he followed the preachings of Islam. But Bangabandhu was against the political use of religion. He condemned the Muslim League’s practice of using the slogan of Islam and not paying attention to the economic well-being of the people which he argued was the goal for which “the working class, the peasants, and the labourers had made sacrifice during the movement for independence.”

Socialism

Equality, freedom from exploitation, and oppression

In his Unfinished Memoirs Bangabandhu writes:

“I myself am no communist, but I believe in socialism and not in capitalism. I believe capital is a tool of the oppressor. As long as capitalism is the mainspring of the economic order people all over the world will continue to be oppressed.”

By socialism he meant a system that would free people from exploitation and oppression and remove inequality. He visited China in 1952 which left a deep imprint in his mind. He found great differences in the living conditions of people in Pakistan and China which he attributed to the differences in the two political systems.

Bangabandhu believed that the government has a role to play in removing inequality and freeing people from exploitation. He admired the priorities set by the Chinese government in improving the socio-economic conditions of the people. He writes:

“Everywhere we could see new schools and colleges coming up. The government has taken charge of education.” He further writes:

“The communist government had confiscated the land owned by landlords and had distributed it among all farmers. Thus landless peasants had become land owners. China now belonged to peasants and workers and the class that used to dominate and exploit had had their day.”

He did not want to see inequality grow in Bangladesh. In the council session of the AL held during April 7-8, 1972, he reiterated his commitment to promote an exploitation-free socio-economic system and socialism was formally adopted as one of the ideals of the party. In the next council session of the party held in 1974 he, again, pledged to work for freeing the nation of exploitation and oppression.

People Orientation

People’s issues, people’s politics

Often we find leaders who lead people towards great goals but they do not become emotionally involved with the people. Bangabandhu was an exception. When I compare the speeches of various leaders of the world with those of Bangabandhu, one of his off-repeated expressions — “love for people” — stands out as unique. He often talked about his love for people and people’s love for him in return.

He always prioritized the issues that are upper-most in ordinary people’s lives. His politics was people’s politics. During the campaign for Pakistan when famine struck, he worked in feeding centres for the famine victims. He worked to rescue the victims of communal riots in Kolkata. He participated in street rallies demanding food security for the poor in East Bengal. His political philosophy was not centred only around the goal of getting state power: He developed his political ideas by being involved with the concerns of the ordinary masses.

This people’s orientation made him a pragmatist. In his diaries he constantly refers to issues that would affect ordinary people’s everyday life such as the rise in essential commodity prices or tax increase or flood or famine.

At one level, Bangabandhu was a man of the masses. He learned about people’s aspirations from them. At another level he was the leader of the people. He carried forward ordinary people’s aspirations. He had faith in people. That is why he could call upon people on March 7, 1971 to join the liberation struggle with “whatever little they have.”

Four guiding principles of state

We see the reflections of Banganabdhu’s political philosophy in the four guiding principles of state adopted by our constitution: Nationalism, democracy, secularism, and socialism. He defended these four principles in various speeches delivered in the parliament, in the party forums, and in addresses to the nation.

Bangabandhu used to articulate the goals of his life’s work in two simple words. He would either say he wants to build again “Shonar Bangla” or he would say he wants to bring “a smile on the faces of the poor and unhappy people.” Bangabandhu never talked about GDP growth or other theoretical issues. He knew very well how precious a smile was and his goal was to achieve that priceless objective.

Rounaq Jahan is a Distinguished Fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), Dhaka, Bangladesh.